|

|

CHAPTER XVIThe First American Counterattack |

The Foundation of Freedom is the Courage of Ordinary PeopleHistory |

| What is necessary to be performed in the heat of action should constantlybe practiced in the leisure of peace. |

| VEGETIUS, Military Institutions of the Romans |

The enemy drive on Pusan from the west along the Chinju-Masan corridorcompelled General Walker to concentrate there all the reinforcements thenarriving in Korea. These included the 5th Regimental Combat Team and thelist Provisional Marine Brigade-six battalions of infantry with supportingtanks and artillery. Eighth Army being stronger there than at any otherpart of the Pusan Perimeter, General Walker decided on a counterattackin this southernmost corridor of the Korean battlefront. It was to be thefirst American counterattack of the war.

The plan for a counterattack grew out of a number of factors-studiesby the Planning Section, G-3, Eighth Army; the arrival of reinforcements;and intelligence that the North Koreans were massing north of Taegu. Althougharmy intelligence in the first days of August seemed to veer toward theopinion that the enemy was shifting troops from the central to the southernfront, perhaps as much as two divisions, it soon changed to the beliefthat the enemy was massing in the area above Taegu. [1]

The Army G-3 Planning Section at this time proposed two offensive actionsin the near future. First, Eighth Army would mount an attack in the Masan-Chinjuarea between 5-10 August. Secondly, about the middle of the month, thearmy would strike in a general offensive through the same corridor, driveon west as far as Yosu, and there wheel north along the Sunch'on-Chonju-Nonsanaxis toward the Kum River-the route of the N.K. 6th Divisionin reverse. This general offensive plan was based on the expected arrivalof the ad Infantry Division and three tank battalions by 15 August. Theplanning study for the first attack stated that the counterattack force"should experience no difficulty in securing Chinju." [2]

General Walker and the Eighth Army General Staff studied the proposalsand, in a conference on the subject, decided the Army could not supportlogistically a general offensive and that there would be insufficient troopsto carry it out. The conference, however, approved the proposal for a counterattackby Eighth Army reserve toward Chinju. One of the principal purposes ofthe counterattack was to relieve enemy pressure against the perimeter inthe Taegu area by forcing the diversion of some North Korean units southwards.[3]

The attack decided upon, General Walker at once requested the FifthAir Force to use its main strength from the evening of 5 August through6 August in an effort to isolate the battlefield and to destroy the enemybehind the front lines between Masan and the Nam River. He particularlyenjoined the commanding general of the Fifth Air Force to prevent the movementof hostile forces from the north and northwest across the Nam into thechosen battle sector. [4]

On 6 August Eighth Army issued the operational directive for the attack,naming Task Force Kean as the attack force and giving the hour of attackas 0630 the next day. [5] The task force was named for its commander, Maj.Gen. William B. Kean, Commanding General of the 25th Division.

Altogether, General Kean had about 20,000 men under his command at thebeginning of the attack. [6] Task Force Kean was composed of the 25th InfantryDivision (less the 27th Infantry Regiment and the 8th Field Artillery Battalion,which were in Eighth Army reserve after their relief at the front on 7August), with the 5th Regimental Combat Team and the 1st Provisional MarineBrigade attached. It included two medium tank battalions, the 89th (M4A3)and the fist Marine (M26 Pershings). The 25th Division now had three infantrybattalions in each of its regiments, although all were understrength. [7]

The terrain and communications of this chosen field for counterattackwere to some extent known to the American commanders. American units hadadvanced or retreated over its major roads as far as Hadong in the precedingtwo weeks. Certain topographic features clearly defined and limited thecorridor, making it a segment of Korea where a planned operation couldbe executed without involving any other part of the Perimeter.

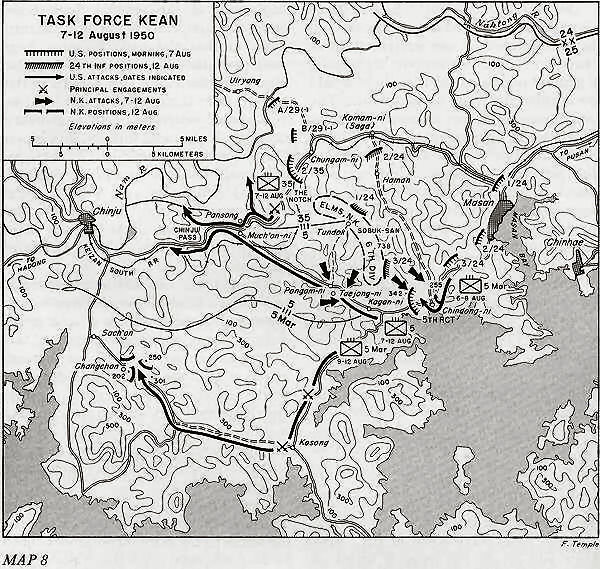

The Chinju-Masan corridor is limited on the south by the Korean Strait,on the north by the Nam River from Chinju to its confluence with the Naktong,fifteen miles northwest of Masan. Masan, at the head of Masan Bay, is atthe eastern end of the corridor; Chinju, at the western end of the corridor,is 27 air miles from Masan. The shortest road distance between the two places is more than 40 miles. The corridoraverages about 20 miles in width. (Map 8)

The topography of the corridor consists mostly of low hills interspersedwith paddy ground along the streams. South of the Nam, the streams rungenerally in a north-south direction; all are small and fordable in dryweather. In two places mountain barriers cross the corridor. One is justeast of Chinju; the main passage through it is the Chinju pass. The secondand more dominant barrier is Sobuk-san, about eight miles west of Masan.

The main east-west highway through the corridor was the two-lane all-weatherroad from Masan through Komam-ni, Chungam-ni, and Much'on-ni to Chinju.The Keizan South Railroad parallels this main road most of the way throughthe corridor. It is single track, standard gauge, and has numerous tunnels,cuts, and trestles.

An important spur road slanting southeast from Much'on-ni connects itwith the coastal road three miles west of Chindong-ni and ten miles fromMasan. The coastal, and third, road hugs the irregular southern shore linefrom Masan to Chinju by way of Chindong-ni, Kosong, and Sach'on.

The early summer of 1950 in Korea was one of drought, and as such wasunusual. Normally there are heavy monsoon rains in July and August withan average of twenty inches of rain; but in 1950 there was only about one-fourththis amount. The cloudless skies over the southern tip of the peninsulabrought scorching heat which often reached 105° and sometimes 120°.This and the 60-degree slopes of the hills caused more casualties fromheat exhaustion among newly arrived marine and army units in the firstweek of the counterattack than enemy bullets.

The army plan for the attack required Task Force Kean to attack westalong three roads, seize the Chinju pass (Line Z in the plan), and securethe line of the Nam River. Three regiments would make the attack: the 35thInfantry along the northernmost and main inland road, the 5th RegimentalCombat Team along the secondary inland road to the Much'on-ni road juncture,and the 5th Marines along the southern coastal road. This placed the marineson the left flank, the 5th Regimental Combat Team in the middle, and the35th Infantry on the right flank. The 5th Regimental Combat Team was tolead the attack in the south, seize the road junction five miles west ofChindong-ni, and continue along the right-hand fork. The marines wouldthen follow the 5th Regimental Combat Team to the road junction, take theleft-hand fork, and attack along the coastal road. This plan called forthe 5th Regimental Combat Team to make a juncture with the 35th Infantryat Much'on-ni, whence they would drive on together to the Chinju pass,while the marines swung southward along the coast through Kosong and Sach'onto Chinju. The 5th Regimental Combat Team and the 5th Marines, on the nightof 6-7 August, were to relieve the 27th Infantry in its front-line defensivepositions west of Chindong-ni. The 27th Infantry would then revert to armyreserve in an assembly area at Masan. [8]

While Task Force Kean attacked west, the 24th Infantry Regiment wasto clean out the enemy from the rear area, giving particular attentionto the rough, mountainous ground of Sobuk-san between the 35th and 5thRegiments. It also was to secure the lateral north-south road running fromKomam-ni through Haman to Chindong-ni. Task Force Min, a regiment-sizedROK force, was attached to the 24th Infantry to assist in this mission.[9]

On the eve of the attack, Eighth Army intelligence estimated that theN.K. 6th Division, standing in front of Task Force Kean,numbered approximately 7,500 effectives. Actually, the 6th Divisionnumbered about 6,000 men at this time. But the 83d MotorizedRegiment of the 105th Armored Division hadjoined the 6th Division west of Masan, unknown to EighthArmy, and its strength brought the enemy force to about 7,500 men, theEighth Army estimate. Army intelligence estimated that the 6th Division would be supported by approximately 36 pieces of artillery and 25 tanks.[10]

On the right flank of Task Force Kean, the 2d Battalion of the 35thInfantry led the attack west on 7 August. Only the day before, an enemyattack had driven one company of this battalion from its position, buta counterattack had regained the lost ground. Now, as it crossed the lineof departure at the Notch three miles west of Chungam-ni, the battalionencountered about 500 enemy troops supported by several self-propelledguns. The two forces joined battle at once, a contest that lasted fivehours before the 2d Battalion, with the help of an air strike, securedthe pass and the high ground northward.

After this fight, the 35th Infantry advanced rapidly westward and byevening stood near the Much'on-ni road fork, the regiment's initial objective.In this advance, the 35th Infantry inflicted about 350 casualties on theenemy, destroyed 2 tanks, 1 76-mm. self-propelled gun, 5 antitank guns,and captured 4 truckloads of weapons and ammunition, several brief casesof documents, and 3 prisoners. Near Pansong, Colonel Fisher's men overranwhat they thought had been the N.K. 6th Division commandpost, because they found there several big Russian-built radios and otherheadquarters equipment. For the 35th Regiment, the attack had gone accordingto plan. [11]

The next day, 8 August, the regiment advanced to the high ground justshort of the Much'on-ni road fork. There Fisher received orders from GeneralKean to dig in and wait until the 5th Regimental Combat Team could comeup on his left and join him at Much'on-ni. While waiting, Fisher's menbeat off a few enemy attacks and sent out strong combat patrols that probedenemy positions as far as the Nam River. [12]

Behind and on the left of the 35th Infantry, in the mountain mass thatseparated it from the other attack columns, the fight was not going well.From this rough ground surrounding Sobuk-san, the 24th Infantry was supposedto clear out enemy forces of unknown size, but believed to be small. Affairsthere had taken an ominous turn on 6 August, the day preceding Task ForceKean's attack, when North Koreans ambushed L Company of the 24th Infantrywest of Haman and scattered I Company, killing twelve men. One officerstated that he was knocked to the ground three times by his own stampedingsoldiers. The next morning he and the 3d Battalion commander located thebattalion four miles to the rear in Haman. Not all the men panicked. Pfc.William Thompson of the Heavy Weapons Company set up his machine gun andfired at the enemy until he was killed by grenades. [13]

Sobuk-san remained in enemy hands.

American units assigned to sweep the area were unable to advance farenough even to learn the strength of the enemy in this mountain fastnessbehind Task Force Kean. Col. Arthur S. Champney succeeded Col. Horton V.White in command of the 24th Regiment in the Sobuk-san area on 6 August.

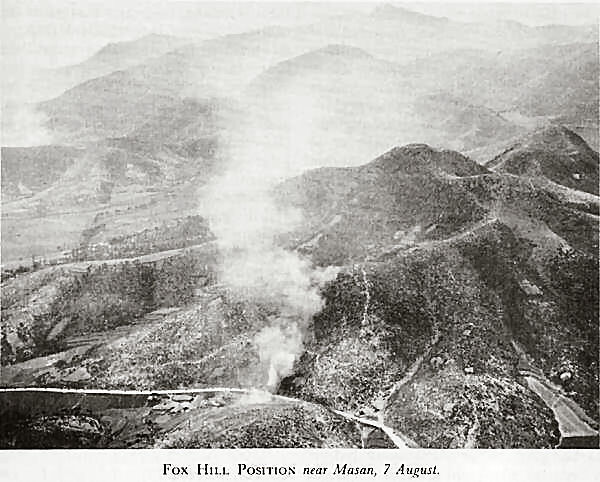

Before beginning the account of Task Force Kean's attack in the southernsector near Chindong-ni it is necessary to describe the position takenthere a few days earlier by the 2d Battalion, 5th Regimental Combat Team.Lt. Col. John L. Throckmorton, a West Point graduate of the Class of 1935,commanded this battalion. It was his first battalion command in combat.Eighth Army had moved the battalion from the docks of Pusan to Chindong-nion 2 August to bolster the 27th Infantry. Throckmorton placed his troopson the spur of high ground that came down from Sobuk-san a mile and a halfwest of Chindong-ni, and behind the 2d Battalion, 27th Infantry, whichwas at Kogan-ni. The highest point Throckmorton's troops occupied was Yaban-san(Hill 342), about a mile north of the coastal road. A platoon of G Companyoccupied this point, Fox Hill, as the battalion called it. Fox Hill wasmerely a high point on a long finger ridge that curved down toward Chindong-nifrom the Sobuk-san peak. Beyond Fox Hill this finger ridge climbed everhigher to the northwest, culminating three miles away in Sobuk-san (Hill738), 2,400 feet high.

The next morning, 3 August, North Koreans attacked and drove the platoonoff Fox Hill. That night F Company of the 5th Infantry counterattackedand recaptured the hill, which it held until relieved there by marine troopson 8 August. Nevertheless, Throckmorton's battalion was in trouble rightup to the moment of the Eighth Army counterattack. There was every indicationthat enemy forces held the higher Sobuk-san area. [14]

On the evening of 6 August the 27th Infantry Regiment and the 2d Battalion,5th Regimental Combat Team, held the front lines west of Chindong-ni. The27th Regiment was near the road; the 2d Battalion, 5th Regimental CombatTeam, on higher ground to the north. During the evening the rest of the5th Regimental Combat Team relieved 27th Infantry front-line troops, andthe 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, relieved the 1st Battalion, 27th Infantry,in its reserve position. The next morning the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines,was to relieve the 2d Battalion, 5th Regimental Combat Team, on the highground north of the road. When thus relieved, the 5th Regimental CombatTeam was to begin its attack west.

During the night of 6-7 August, North Koreans dislodged a platoon ofThrockmorton's troops from a saddle below Fox Hill and moved to a pointeast and south of the spur. From this vantage point the following morningthey could look down on the command posts of the 5th Marines and the 5thRegimental Combat Team, on the artillery emplacements, and on the mainsupply road at Chindong-ni.

That morning, 7 August, a heavy fog in the coastal area around Chindong-niprevented an air strike scheduled to precede the Task Force Kean infantry attack. The artillery fired a twenty-minutepreparation. At 0720 the infantry then moved out in the much-heralded armycounterattack. The 1st Battalion, 5th Regimental Combat Team, led off downthe road from its line of departure just west of Chindong-ni and arrivedat the road junction without difficulty. There, instead of continuing onwest as it was supposed to do, it turned left, and by noon was on a hillmass three miles south of the road fork and on the road allotted to themarine line of advance. How it made this blunder at the road fork is hardto understand. As a result of this mistake the hill dominating the roadjunction on the northwest remained unoccupied. The 1st Battalion was supposedto have occupied it and from there to cover the advance of the remainderof the 5th Regimental Combat Team and the 5th Marines. [15]

After the 1st Battalion, 5th Regimental Combat Team, had started westward,the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, commanded by Lt. Col. Harold S. Roise, movedout at 1100 to relieve Throckmorton's battalion on the spur running upto Fox Hill. It ran head-on into the North Koreans who had come aroundto the front of the spur during the night. It was hard to tell who wasattacking whom. The day was furnace hot with the temperature standing at112°. In the struggle up the slope the Marine battalion had approximatelythirty heat prostration cases, six times its number of casualties causedby enemy fire. In the end its attack failed. [16]

The fight west of Chindong-ni on the morning of 7 August was in facta general melee. Even troops of the 27th Infantry, supposed to be in reservestatus, were involved. The general confusion was deepened when the treadsof friendly tanks cut up telephone line strung along the roadside, causingcommunication difficulties. Finally at 1120, when marine troops completedrelief of the 27th Infantry in its positions, Brig. Gen. Edward A. Craig,commanding the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, assumed command, on GeneralKean's orders, of all troops on the Chindong-ni front. He held that commanduntil the afternoon of 9 August. [17]

While these untoward events were taking place below it, F Company ofthe 5th Regimental Combat Team on the crest of Fox Hill was cut off. At1600 an airdrop finally succeeded on the third try in getting water andsmall arms and 60-mm. mortar ammunition to it. The enemy got the firstdrop. The second was a mile short of the drop zone.

Failing the first day to accomplish its mission, the 2d Battalion, 5thMarines, resumed its attack on Fox Hill the next morning at daybreak afteran air strike on the enemy positions. This time, after hard fighting, itsucceeded. In capturing and holding the crest, D Company of the Marinebattalion lost 8 men killed, including 3 officers, and 28 wounded. Theenemy losses on Hill 342 are unknown, but estimates range from 150 to 400. [18]

The events of 7 August all across the Masan front showed that Task ForceKean's attack had collided head-on with one being delivered simultaneouslyby the N.K. 6th Division.

All of Task Force Kean's trouble was not confined to the area west ofChindong-ni; there was plenty of it eastward. For a time it seemed as ifthe latter might be the more dangerous. There the North Koreans threatenedto cut the supply road from Masan. There is no doubt that Task Force Keanhad an unpleasant surprise on the morning of 7 August when it discoveredthat the enemy had moved around Chindong-ni during the night and occupiedHill 255 just east of the town, dominating the road in its rear to Masan.

Troops of the 2d Battalion, 24th Infantry, and of the 3d Battalion,5th Marines, tried unsuccessfully during the day to break this roadblock.In the severe fighting there, artillery and air strikes, tanks and mortarspounded the heights trying to dislodge the enemy. Batteries B and C ofthe 159th Field Artillery Battalion fired 1,600 rounds during 7-8 Augustagainst this roadblock. Colonel Ordway, at the marines' request, also directedthe fire of part of the 555th Artillery Battalion against this height.But the enemy soldiers stubbornly held their vantage point. Finally, afterthree days of fighting, the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, and elements oftwo battalions of the 24th Infantry joined on Hill 255 east of Chindong-ni,shortly after noon on 9 August, and reduced the roadblock. There were 120counted enemy dead, with total enemy casualties estimated at 600. On thefinal day of this action, the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, which carriedthe brunt of the attack, had 70 casualties, half of them caused by heatexhaustion. During its two-day part in the fight for this hill, H Companyof the marines suffered 16 killed and 36 wounded. [19]

When Throckmorton's 2d Battalion, 5th Regimental Combat Team, came offFox Hill on 8 August after the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, had relievedit there, it received the mission of attacking west immediately, to seizethe hill northwest of the road junction that the 1st Battalion was supposedto have taken the day before. At this time, Throckmorton had only two companieseffective after his week of combat on Fox Hill. Nevertheless, he movedagainst the hill but was unable to take it. His attack was weakened whensupporting artillery failed to adjust on the target.

In the late afternoon, General Kean came up to the 2d Battalion positionand, with Colonel Ordway present, said to Colonel Throckmorton, "Iwant that hill tonight." Throckmorton decided on a night attack withhis two effective companies, G and E. He put three tanks and his 4.2-inchand 81-mm. mortars in position for supporting fire. That night his mengained the hill, although near the point of exhaustion. [20]

For three days the N.K. 6th Division had pinned down TaskForce Kean, after the latter had jumped off at Chindong-ni. Finally, on9 August, the way was clear for it to start the maneuver along the middleand southern prongs of the planned attack toward Chinju.

On the afternoon of 9 August, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, took overfrom the 1st Battalion, 5th Regimental Combat Team, the hill position onthe coastal road which the latter had held for three days. The army battalionthen moved back to the road fork and turned down the right-hand road. Atlast it was on the right path, prepared to attack west with the remainderof its regiment. [21]

The 5th Marines that afternoon moved rapidly down the coastal road,leapfrogging its battalions in the advance. Corsairs of the 1st MarineAir Wing, flying from the USS Sicily and USS BadoengStrait in the waters off the coast, patrolled the road and adjoining hills ahead of the troops.This close air support delivered strikes within a matter of minutes aftera target appeared. [22]

General Kean pushed his unit commanders hard to make up for lost time,now that the attack had at last started. The pace was fast, the sun brightand hot. Casualties from heat exhaustion on 10 August again far exceededthose from enemy action. The rapid advance that day after the frustrationsof the three preceding ones caused some Tokyo spokesman to speak of the"enemy's retreat" as being "in the nature of a rout,"and correspondents wrote of the action as a "pursuit." And soit seemed for a time. [23]

Just before noon on the 11th, after a fight on the hills bordering theroad, the leading Marine battalion (3d) neared the town of Kosong. Itssupporting artillery from the 1st Battalion, 11th Marines, adjusting fireon a crossroads west of the town, chanced to drop shells near camouflagedenemy vehicles. Thinking its position had been discovered, the enemy forcequickly entrucked and started down the road toward Sach'on and Chinju.This force proved to be a major part of the 83d MotorizedRegiment of the 105th Armored Division, whichhad arrived in the Chinju area to support the N.K. 6th Division.

Just as the long column of approximately 200 vehicles, trucks, jeeps,and motorcycles loaded with troops, ammunition, and supplies got on theroad, a flight of four Corsairs from the Badoeng Strait cameover on a routine reconnaissance mission ahead of the marines. They swunglow over the enemy column, strafing the length of it. Vehicles crashedinto each other, others ran into the ditches, some tried to get to thehills off the road. Troops spilled out seeking cover and concealment. Theplanes turned for another run. The North Koreans fought back with smallarms and automatic weapons and hit two of the planes, forcing one downand causing the other to crash. This air attack left about forty enemyvehicles wrecked and burning. Another flight of Marine Corsairs and AirForce F-51's arrived and continued the work of destruction. When the groundtroops reached the scene later in the afternoon, they found 31 trucks,24 jeeps, 45 motorcycles, and much ammunition and equipment destroyed orabandoned. The marine advance stopped that night four miles west of Kosong.[24]

The next morning, 12 August, the 1st Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col.George R. Newton, passed through the 3d Battalion and led the Marine brigadein what it expected to be the final lap to Sach'on, about 8 miles belowChinju. Advancing 11 miles unopposed, it came within 4 miles of the townby noon. An hour later, three and a half miles east of Sach'on, the Marine column entered an enemy ambush at the villageof Changchon or, as the troops called it, Changallon. Fortunately for themarines, a part of the 2d Battalion, 15th Regiment,and elements of the 83d Motorized Regiment that lay in waitin the hills cupping the valley disclosed the ambush prematurely. A heavyfight got under way and continued through the afternoon and into the evening.Marine Corsairs struck repeatedly. In the late afternoon, the 1st Battaliongained control of Hills 301 and 250 on the right, and Hill 202 on the left,of the road.

On Hill 202, before daylight the next morning, a North Korean forceoverran the 3d Platoon of B Company. One group apparently had fallen asleepand all except one were killed. Heavy casualties were inflicted also onanother nearby platoon of B Company. Shortly after daylight the marineson Hill 202 received orders to withdraw and turn back toward Masan. Duringthe night, B Company lost 12 men killed, 16 wounded, and 9 missing, thelast presumed dead. [25]

Just before noon of the 12th, General Kean had ordered General Craigto send one battalion of marines back to help clear out enemy troops thathad cut the middle road behind the 5th Regimental Combat Team and had itsartillery under attack. An hour after noon the 3d Battalion was on itsway back. That evening Craig was called to Masan for a conference withKean. There he received the order to withdraw all elements of the brigadeimmediately to the vicinity of Chingdong-ni. Events taking place at otherpoints of the Pusan Perimeter caused the sudden withdrawal of the Marinebrigade from Task Force Kean's attack. [26]

Simultaneously with the swing of the Marine brigade around the southerncoastal loop toward Chinju, the 5th Regimental Combat Team plunged aheadin the center toward Much'on-ni, its planned junction point with the 35thInfantry. On 10 August, as the combat team moved toward Pongam-ni, aerialobservation failed to sight enemy troop concentrations or installationsahead of it. Naval aircraft, however, did attack the enemy north of Pongam-niand bombed and strafed Tundok still farther north in the Sobuk-san miningregion.

The 1st Battalion, under the command of Lt. Col. John P. Jones, attackeddown the right (north) side of the road and the 2d Battalion, under ColonelThrockmorton, down the left (south) side. The 1st Battalion on its sideencountered the enemy on the hills near Pongam-ni, but was able to enterthe town and establish its command post there.

The village of Pongam was a nondescript collection of perhaps twentymud-walled and thatch-roofed huts clustered around a road junction. Itand Taejong-ni were small villages only a few hundred yards apart on theeast side of the pass. The main east-west road was hardly more than a countrylane by American standards. About 400 yards northeast of Pongam-ni rosea steep, barren hill, the west end of a long ridge that paralleled themain east-west road on the north side at a distance of about 800 yards.The enemy occupied this ridge. Northward from Pongam-ni extended a 500-yard-widevalley. A narrow dirt trail came down it to Pongam-ni from the Sobuk-sanmining area of Tundok to the north. The stream flowing southward throughthis valley joined another flowing east at the western edge of Pongam-ni.There a modern concrete bridge, in sharp contrast to the other structures,spanned the south-flowing stream. West of the villages, two parallel ridgescame together about 1,000 yards away, like the two sides of an invertedV. The southern ridge rose sharply from the western edge of the village.The main road ran westward along its base and climbed out of the valleyat a pass where this ridge joined the other slanting in from the north.Immediately west of Pongam-ni the two ridges were separated by a 300-yard-widevalley. The northern ridge was the higher.

On 10 August the 2d Battalion, 5th Regimental Combat Team, held thesouthern of these two ridges at Pongam-ni and B and C Companies of the1st Battalion held the eastern part of the northern one. The enemy heldthe remainder of this ridge and contested control of the pass.

During the day the regimental support artillery came up and went intopositions in the stream bed and low ground at Pongam-ni and Taejong-ni.A Battery of the 555th Field Artillery Battalion emplaced under the concretebridge at Pongam-ni, and B Battery went into position along the streambank at the edge of the village. Headquarters Battery established itselfin the village. The 90th Field Artillery Battalion, less one battery, hademplaced on the west side of the south-flowing stream. All the artillerypieces were on the north side of the east-west road. The 5th RegimentalCombat Team headquarters and C Battery of the 555th Field Artillery Battalionwere eastward in a rear position. [27]

That night, 10-11 August, North Koreans attacked the 1st Battalion andthe artillery positions at Pongam-ni. The action continued after daylight.During this fight, Lt. Col. John H. Daly, the 555th Field Artillery Battalioncommander, lost communication with his A Battery. With the help of someinfantry, he and Colonel Jones, the 1st Battalion commander, tried to reachthe battery. Both Daly and Jones were wounded, the latter seriously. Dalythen assumed temporary command of the infantry battalion. As the day progressed the enemy attacks at Pongam-ni dwindled and finally ceased.

When the 3d Battalion had continued on westward the previous afternoonthe 5th Regimental Combat Team headquarters and C Battery, 555th FieldArtillery Battalion, east of Pongam-ni, had been left without protectinginfantry close at hand. North Koreans attacked them during the night atthe same time Pongam-ni came under attack. The Regimental Headquartersand C Battery personnel defended themselves successfully. On the morningof the 11th, close-in air strikes helped turn the enemy back into the hills.Colonel Throckmorton's 2d Battalion headquarters had also come under attack.He called E Company from its Pongam-ni position to help beat off the enemy.[28]

Colonel Ordway's plan for passing the regiment westward through Pongam-niwas for the 2d Battalion to withdraw from the south ridge and start themovement, after the 1st Battalion had secured the north ridge and the pass.The regimental trains were to follow and next the artillery. The 1st Battalionwas then to disengage and bring up the rear.

After Colonel Jones was evacuated, Colonel Ordway sent Lt. Col. T. B.Roelofs, regimental S-2 and formerly the battalion commander, to take commandof the 1st Battalion. Roelofs arrived at Pongam-ni about 1400, 11 August,and assumed command of the 1st Battalion. Ordway had given him orders toclear the ridge north of the road west of Pongam-ni, secure the pass, protectthe combat team as it moved west through the pass, and then follow it.Roelofs met Daly at Pongam-ni, consulted with him and the staff of the1st Battalion, made a personal reconnaissance of the area, and then issuedhis attack order to clear the ridge and secure the pass.

Colonel Roelofs selected B Company to make the main effort. He broughtit down from the north ridge to the valley floor, where it rested brieflyand was resupplied with ammunition. Just before dusk, it moved to the headof the gulch and attacked the hill on the right commanding the north sideof the pass. At the same time, C Company attacked west along the northridge to effect a junction with B Company. The artillery and all availableweapons of the 2d Battalion supported the attack; the artillery fire wasaccurate and effective. Before dusk B Company had gained and occupied thecommanding ground north of the pass. [29]

One platoon of A Company, reinforced with a section of tanks, remainedin its position north of Pongam-ni on the Tundok road, to protect fromthat direction the road junction village and the artillery positions. Theremainder of A Company relieved the 2d Battalion on the south ridge, whenit withdrew from there at 2100 to lead the movement westward.

His battalion's attack apparently a success, Colonel Roelofs establishedhis command post about 300 yards west of Pongam-ni in a dry stream bedsouth of the road, crawled under the trailer attached to his jeep, and went tosleep.

As a result of the considerable enemy action during the night of 10-11August and during the day of the 11th, Colonel Ordway decided that he couldnot safely move the regimental trains and the artillery through the passduring daylight, and accordingly he had made plans to do it that nightunder cover of darkness. That afternoon, however, Ordway was called tothe radio to speak to General Kean. The 25th Division commander wantedhim to move forward rapidly and said that a battalion of the 24th Infantrywould come up and protect his right (north) flank. Ordway had a lengthyconversation with the division and task force commander before the latterapproved the delay until after dark for the regimental movement. GeneralKean apparently did not believe any considerable force of enemy troopswas in the vicinity of Pongam-ni, despite Ordway's representations to thecontrary.

General Kean, on his part, was under pressure at this time because duringthe day Eighth Army had sent a radio message to him, later confirmed byan operational directive, to occupy and defend the Chinju pass line; tomove Task Force Min, a regimental sized ROK unit, to Taegu for releaseto the ROK Army; and to be ready to release the 1st Provisional MarineBrigade and the 5th Regimental Combat Team on army order. This clearlyforeshadowed that Task Force Kean probably would not be able to hold itsgains, as one or more of its major units apparently were urgently neededelsewhere.

About 2100 hours, as Throckmorton's 2d Battalion, C Battery of the 555th,and the trains were forming on the road, the regimental S-3 handed ColonelOrdway a typed radio order from the commanding general of the 25th Division.It ordered him to move the 2d Battalion and one battery of artillery throughthe pass at once, but to hold the rest of the troops in place until daylight.Ordway felt that to execute the order would have catastrophic effects.He tried to reach the division headquarters to protest it, but could notestablish communication. On reflection, Ordway decided that some aspectof the "big picture" known only to the army and division commandersmust have prompted the order. With this thought governing his actions heissued instructions implementing the division order. [30]

In the meantime the 2d Battalion had moved through the pass, and onceover its rim was out of communication with the regiment. Ordway tried andfailed several times to reach it by radio during the night. In effect,though Throckmorton thought he was the advance guard of a regimental advance,he was on his own. Ordway and the rest of the regiment could not help himif he ran into trouble nor could he be called back to help them. In themovement of the 2d Battalion and C and Headquarters Batteries, ColonelDaly was wounded a second time and was evacuated. Colonel Throckmorton's2d Battalion cleared the pass before midnight. On the west side it came under light attackbut was able to continue on for five miles to Taejong-ni, where it wentinto an assembly area for the rest of the night.

While these events were taking place at Pongam-ni during daylight andthe evening of the 11th, the main supply road back toward Chindong-ni wasunder sniper fire and various other forms of attack. Three tanks and anassault gun escorted supply convoys to the forward positions. [31]

By midnight of 11 August, the 555th (Triple Nickel) Field ArtilleryBattalion (105-mm. howitzers), less C Battery, and Headquarters and A Batteries,90th Field Artillery Battalion (155-mm. howitzers)-emplaced at Pongam-niand Taejong-ni-had near them only the 1st Battalion north of the road.The regimental headquarters and the guns of the 159th Field Artillery Battalionwere emplaced a little more than a mile behind them (east) along the road.[32]

Sometime after 0100, 12 August, Colonel Roelofs was awakened by hisexecutive officer, Capt. Claude Baker. Baker informed him that the battalionhad lost contact with C Company on the ridge northward and sounds of combatcould be heard coming from that area. When further efforts to reach thecompany by telephone and radio failed, Roelofs sent runners and a wirecrew out to try to re-establish contact. He then informed Colonel Ordwayof this new development, and urged speedy movement of the trains and artillerywestward through the pass. But Ordway reluctantly held firm to divisionorders not to move until after daylight.

Roelofs, taking two of his staff officers with him, set out in his jeepeastward toward Pongam-ni. He noted that the regimental trains had assembledon the road and apparently were only awaiting orders before moving. Atthe bridge in Pongam-ni he saw several officers of the 555th Field ArtilleryBattalion, who also seemed to be waiting orders to start the movement.Roelofs turned north at Pongam-ni on the dirt trail running toward theSobuk-san mining area. He drove up that road until he came to the A Companyinfantry platoon and the section of tanks. They were in position. Theytold Roelofs they had heard sounds of small arms fire and exploding grenadesin the C Company area on the ridge to their left (west), but nothing else.[33]

Upon returning to his command post Roelofs learned that contact stillhad not been re-established with C Company. The runners sent out had returnedand said they could not find the company. The wire crew was missing. Membersof the battalion staff during Roelofs' absence had again heard sounds ofcombat in the company area. They also had seen flares there. This was interpretedto mean that enemy troops held it and were signaling to other enemy units.From his position in the valley at regimental headquarters, Colonel Ordwaycould see that elements of the 1st Battalion, probably C Company, were being driven from the ridge. Roelofs again urged Colonel Ordway to startthe trains out of the gulch.

Still unable to contact the division, Ordway now decided to move thetrains and artillery out westward while it was still dark, despite divisionorders to wait for daylight. He felt that with the enemy obviously gainingcontrol of the high ground above Pongam-ni, movement after daylight wouldbe impossible or attended by heavy loss. The battalion of the 24th Infantrypromised by the division had not arrived. About 0400 Ordway gave the orderfor the trains to move out. They were to be followed by the artillery,and then the 1st Battalion would bring up the rear. In the meantime, thebattalion was to hold open the pass and protect the regimental column.[34]

Despite Ordway's use of messengers and staff officers, and his own effortsthe trains seemed unable to move and a bad traffic jam developed. Movementof the trains through the pass should have been accomplished in twentyminutes, but it required hours. During the hour or more before daylight,no vehicle in Ordway's range of vision moved more than ten or twenty feetat a time. One of the factors creating this situation was caused when theMedical Company tried to move into the column from its position near the1st Battalion command post. An ambulance hung up in a ditch and stoppedeverything on the road behind it until it could be pulled out.

With the first blush of dawn, enemy fire from the ridge overlookingthe road began to fall on the column. At first it was light and high. ColonelOrdway got into his jeep and drove westward trying to hurry the columnalong. But he accomplished little. After the ambulance got free, however,the movement was somewhat faster and more orderly. Colonel Ordway himselfcleared the pass shortly after daybreak. He noticed that the 1st Battalionwas holding the pass and the hill just to the north of it. West of thepass, Ordway searched for a place to get the trains off the road temporarilyso that the artillery could move out, but he found none suitable. He continuedon until he reached Throckmorton's 2d Battalion bivouac area. The headof the regimental trains had already arrived there. He ordered them tocontinue on west in order to clear the road behind for the remainder ofthe column. Soon one of his staff officers found a schoolyard where thevehicles could assemble off the road, and they pulled in there.

About this time an artillery officer arrived from Pongam-ni and toldOrdway that the artillery back at the gulch had been cut to pieces. Ordwayreturned to the 2d Battalion bivouac and then traveled on eastward towardPongam-ni. On the way he met the 1st Battalion marching west on the road.The troops appeared close to exhaustion. Colonel Roelofs told Ordway thatso far as he could tell the artillerymen had escaped into the hills. Ordwayordered the 1st Battalion into an assembly area and then directed the 2dBattalion to return to Pongam-ni, to cover the rear of the regiment andany troops remaining there.

That morning at dawn, after Colonel Ordway had cleared the pass, ColonelRoelofs watched the column as it tried to clear the gulch area. To his great surprise he discovered movingwith it the section of tanks and the A Company infantry platoon that hehad left guarding the road entering Pongam-ni from the north. He askedthe platoon leader why he had withdrawn. The latter answered that he hadbeen ordered to do so. By the next day this officer had been evacuated,and Colonel Roelofs was never able to learn if such an order had been issuedto him and, if so, by whom. Roelofs ordered the tanks and the infantryplatoon to pull out of the column on to a flat spot near his command post.He intended to send them back to their original position just as soon asthe road cleared sufficiently to enable them to travel. When he reportedthis to Colonel Ordway, he was instructed not to try it, as their movementto the rear might cause such a traffic jam that the artillery could notmove.

About this time, soon after daybreak, enemy infantry had closed in soas virtually to surround the artillery. The North Korean 13th Regimentof the 6th Division, the enemy force at Pongam-ni, now struckfuriously from three sides at the 555th and 90th Field Artillery Battalions'positions. [35] The attack came suddenly and with devastating power. Roelofswas standing in the road facing east toward Pongam-ni, trying to keep thetraffic moving, when in the valley below him he saw streaks of fire thatleft a trail behind. Then came tremendous crashes. A truck blew up on thebridge in a mushroom of flame. The truck column behind it stopped. Menin the vehicles jumped out and ran to the ditches. Roelofs could now seeenemy tanks and self-propelled guns on the dirt trail in the valley northof Pongam-ni, firing into the village and the artillery positions. To theartillerymen, this armed force looked like two tanks and several antitankguns.

The withdrawal of the section of tanks and the A Company infantry platoonfrom its roadblock position had permitted this enemy armor force to approachundetected and unopposed, almost to point-blank range, and with completelydisastrous effects. The Triple Nickel emplacements were in the open andexposed to this fire; those of the 90th were partially protected by terrainfeatures. The 105-mm. howitzers of the 555th Field Artillery Battalionineffectually engaged the enemy armor. The 90th could not depress its 155-mm.howitzers low enough to engage the tanks and the self-propelled guns. Someof the Triple Nickel guns received direct hits. Many of the artillerymenof this battalion sought cover in buildings and under the bridge at Taejong-ni.Some of the buildings caught fire.

Simultaneously with the appearance of the enemy armor, North Koreansmall arms and automatic fire from the ridge north of the road increasedgreatly in volume. This fire caused several casualties among the 4.2-inchmortar crew members and forced the mortar platoon to cease firing and seekcover. The heavy machine gun platoon, fortunately, was well dug in andcontinued to pour heavy fire into the enemy-held ridge. An enemy machinegun opened up from the rear south of the road, but before the gunner gotthe range a truck driver killed him. Other sporadic efforts of a few infiltrating enemy troops in that quarter were suppressed before causing damage.

A lieutenant colonel of artillery came up the road with three or fourmen. He told Roelofs that things were in a terrible condition at the bridgeand in the village. He said the guns were out of action and the truckshad been shot up and that the men were getting out as best they could.As the road traffic thinned out, enemy fire on the road subsided. Roelofsordered the 4.2-inch mortar platoon to move on through the pass. The heavymachine gun platoon followed it. The wounded were taken along; the deadwere left behind. There was no room for them on the few remaining trucksthat would run.

As the last men of the 1st Battalion were moving westward toward thetop of the pass, three medium tanks rolled up the road from Pongam-ni.Roelofs had not known they were there. He stopped one and ordered it tostand by. The tankers told him that everyone they saw at the bridge andalong the stream was dead. To make a last check, Roelofs with several menstarted down anyway. On the way they met Chaplain Francis A. Kapica inhis jeep with several wounded men. Kapica told Roelofs he had brought withhim all the wounded he could find. Roelofs turned back, boarded the waitingtank, and started west. At the pass which his 1st Battalion men still held,he found 23 men from C Company, all that remained of 180. These survivorssaid they had been overrun. Roelofs organized the battalion withdrawalwestward from the pass. In the advance he put A Company, then the C Companysurvivors. Still in contact with enemy, B Company came off the hills northof the pass in platoons. The company made the withdrawal successfully withthe three tanks covering it from the pass. The tanks brought up the rearguard. The time was about 1000.

The situation in the village and at the bridge was not quite what itappeared to be to Roelofs and some of the officers and men who escapedfrom there and reported to him. Soon after the enemy armor came down thetrail from the north and shot up the artillery positions, enemy infantryclosed on the Triple Nickel emplacements and fired on the men with smallarms and automatic weapons. Three of the 105-mm. howitzers managed to continuefiring for several hours after daybreak, perhaps until 0900. Then the enemyoverran the 555th positions. [36]

The 90th Field Artillery Battalion suffered almost as great a calamity.Early in the pre-dawn attack the North Koreans scored direct hits on two155-mm. howitzers and several ammunition trucks of A Battery. Only by fightingresolutely as infantrymen, manning the machine guns on the perimeter andoccupying foxholes as riflemen, were the battalion troops able to repelthe North Korean attack. Pfc. William L. Baumgartner of Headquarters Batterycontributed greatly in repelling one persistent enemy force. He fired atruck-mounted machine gun while companions dropped all around him. Finally,a direct hit on his gun knocked him unconscious and off the truck. After he revived,Baumgartner resumed the fight with a rifle. [37]

At daybreak, Corsairs flew in to strafe and rocket the enemy. They hadno radio communication with the ground troops but, by watching tracer bulletsfrom the ground action, the pilots located the enemy. Despite this closeair support, the artillery position was untenable by 0900. Survivors ofthe 90th loaded the wounded on the few serviceable trucks. Then, with theuninjured giving covering fire and Air Force F-51 fighter planes strafingthe enemy, the battalion withdrew on foot. [38] Survivors credited thevicious close-in attacks of the fighter planes with making the withdrawalpossible. But most of all, the men owed their safety to their own willingnessto fight heroically as infantrymen when the enemy closed with them.

Meanwhile, enemy fire destroyed or burned nearly every vehicle eastof the Pongam-ni bridge.

A mile eastward, another enemy force struck at B Battery, 159th FieldArtillery Battalion. In this action enemy fire ignited several trucks loadedwith ammunition and gasoline. At great personal risk, several drivers droveother ammunition and gasoline trucks away from the burning vehicles. Theattack here, however, was not as intense as that at Pongam-ni and it subsidedabout 0800. [39]

After the artillery positions had been overrun, two tanks of the 25thDivision Reconnaissance Company arrived from the east and tried to driveout the North Koreans and clear the road. MSgt. Robert A. Tedford stoodexposed in the turret of one tank, giving instructions to the driver andgunner, while he himself operated the .50-caliber machine gun. This tankattack failed. Enemy fire killed Tedford, but he snuffed out the livesof some North Koreans before he lost his own. [40]

Meanwhile, at his assembly area five miles westward, Colonel Throckmortonhad received Colonel Ordway's order to return with the 2d Battalion tothe pass area west of Pongam-ni. When he arrived there the fight in thegulch and valley eastward had died down. A few stragglers came into hislines, but none after noon. Believing that enemy forces were moving throughthe hills toward the regimental command post at Taejong-ni, Throckmortonrequested authority to return there. The regimental executive officer grantedthis authority at 1500. [41]

During the morning, General Barth, commander of the 25th Division artillery,tried to reach the scene of the enemy attack. But the enemy had cut theroad and forced him to turn back. North Koreans also ambushed a platoonof the 72d Engineer Combat Battalion trying to help open the road. Barthtelephoned General Kean at Masan and reported to him the extent of thedisaster. Kean at once ordered the 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, to proceedto the scene, and he also ordered the 3d Battalion, 24th Infantry, to attack throughthe hills to Pongam-ni. [42]

The Marine battalion arrived at Kogan-ni, three miles short of Pongam-ni,at 1600 and, with the assistance of air strikes and an artillery barrage,by dark had secured the high ground north of the road and east of Pongam-ni.The next morning the battalion attacked west with the mission of rescuingsurvivors of the 555th Field Artillery Battalion reported to be under thebridge at the village. Colonel Murray in a helicopter tried to delivera message to these survivors, if any (there is no certainty there wereany there), but was driven back by enemy machine gun fire. The marinesreached the hill overlooking Pongam-ni and saw numerous groups of enemytroops below. Before they could attempt to attack into Pongam-ni itselfthe battalion received orders to rejoin the brigade at Masan. [43]

The 3d Battalion, 24th Infantry, likewise did not reach the overrunartillery positions. Lt. Col. John T. Corley, the much-decorated UnitedStates Army battalion commander of World War II, had assumed command ofthe battalion just three days before, on 9 August. Although Eighth Armysent some of the very best unit commanders in the United States Army tothe 24th Regiment to give it superior leadership, the regiment remainedunreliable and performed poorly. On 12 August, Corley's two assault companiesin the first three hours of action against an estimated two enemy companies,and while receiving only a few rounds of mortar fire, dwindled from a strengthof more than 100 men per company to about half that number. There wereonly 10 casualties during the day, 3 of them officers. By noon of the nextday, 13 August, the strength of one company was down to 20 men and of theother to 35. This loss of strength was not due to casualties. Corley'sbattalion attack stopped two and a half miles from the captured artillerypositions. [44]

At Bloody Gulch, the name given by the troops to the scene of the successfulenemy attack, the 555th Field Artillery on 12 August lost all eight ofits 105-mm. howitzers in the two firing batteries there. The 90th FieldArtillery Battalion lost all six 155-mm. howitzers of its A Battery. Theloss of Triple Nickel artillerymen has never been accurately computed.The day after the enemy attack only 20 percent of the battalion troopswere present for duty. The battalion estimated at the time that from 75to 100 artillerymen were killed at the gun positions and 80 wounded, withmany of the latter unable to get away. Five weeks later, when the 25thDivision regained Taejong-ni, it found in a house the bodies of 55 menof the 555th Field Artillery. [45]

The 90th Field Artillery Battalion lost 10 men killed, 60 wounded, and about 30 missing at Bloody Gulch-more than half the men of Headquartersand A Batteries present. Five weeks later when this area again came underAmerican control, the bodies of 20 men of the battalion were found; allof them had been shot through the head. [46]

Four days after the artillery disaster, General Barth had the 555thand 90th Field Artillery Battalions reconstituted and re-equipped withweapons. Eighth Army diverted 12 105-mm. howitzers intended for the ROKArmy to the 25th Division artillery and 6 155-mm. howitzers intended fora third firing battery of the 90th Field Artillery Battalion were usedto re-equip A Battery. Lt. Col. Clarence E. Stuart arrived in Korea fromthe United States on 13 August and assumed command of the 555th Field ArtilleryBattalion.

West of Bloody Gulch, the 2d Battalion, 5th Regimental Combat Team,repulsed a North Korean attack at Taejong-ni on the morning of 13 August.That afternoon, the battalion entrucked and moved on to the Much'on-niroad fork. There it turned east toward Masan.

The 3d Battalion of the 5th Regimental Combat Team, rolling westwardfrom Pongam-ni on the morning of 1l August, had joined the 35th Infantrywhere the latter waited at the Much'on-ni crossroads. From there the twoforces moved on to the Chinju pass. They now looked down on Chinju. Butonly their patrols went farther. On the afternoon of 13 August and thatnight, the 5th Regimental Combat Team traveled back eastward. It was depletedand worn. Military police from the 25th Division were supposed to guideits units to assigned assembly areas. But there was a change in plans,and in the end confusion prevailed as most of the units were led in thedarkness of 13-14 August to a dry stream bed just east of Chindong-ni.The troops were badly mixed there and until daylight no one knew whereanyone else was. [47]

The next morning the 2d Battalion of the 5th Regimental Combat Teammoved around west to Kogan-ni, where it relieved the 3d Battalion, 5thMarines. Colonel Throckmorton succeeded Colonel Ordway in command of theregiment on 15 August.

On 14 August, after a week of fighting, Task Force Kean was back approximatelyin the positions from which it had started its attack. The 35th Regimentheld the northern part of the 25th Division line west of Masan, the 24thRegiment the center, and the 5th Regimental Combat Team the southern part.The Marine brigade was on its way to another part of the Eighth Army line.In the week of constant fighting in the Chinju corridor, from 7 to 13 August,the units of Task Force Kean learned that the front was the four points of the compass, and that it was necessaryto climb, climb, climb. The saffron-colored hills were beautiful to gazeupon at dusk, but they were brutal to the legs climbing them, and out ofthem at night came the enemy.

While Task Force Kean drove westward toward Chinju, enemy mines andsmall arms fire daily cut the supply roads behind it in the vicinity ofChindong-ni. For ten successive days, tanks and armored cars had to opena road so that food supplies might reach a battalion of the 24th Infantryin the Sobuk-san area. The old abandoned coal mines of the Tundok regionon Sobuk-san were alive with enemy troops. The 24th Infantry and ROK troopshad been unable to clear this mountainous region. [48]

At 1550, 16 August, in a radio message to General Kean, Eighth Armydissolved Task Force Kean. [49] The task force had not accomplished whatEighth Army had believed to be easily possible-the winning and holdingof the Chinju pass line. Throughout Task Force Kean's attack, well organizedenemy forces controlled the Sobuk-san area and from there struck at itsrear and cut its lines of communications. The North Korean High Commanddid not move a single squad from the northern to the southern front duringthe action. The N.K. 6th Division took heavy losses in someof the fighting, but so did Task Force Kean. Eighth Army again had underestimatedthe N.K. 6th Division.

Even though Task Force Kean's attack did not accomplish what EighthArmy had hoped for and expected, it nevertheless did provide certain beneficialresults. It chanced to meet head-on the N.K. 6th Divisionattack against the Masan position, and first stopped it, then hurled itback. Secondly, it gave the 25th Division a much needed psychological experienceof going on the offensive and nearly reaching an assigned objective. Fromthis time on, with the exception of the 24th Infantry, the division troopsfought well and displayed a battle worthiness that paid off handsomelyand sometimes spectacularly in the oncoming Perimeter battles. By disorganizingthe offensive operations of the N.K. 6th Division at themiddle of August, Task Force Kean also gained the time needed to organizeand wire in the defenses that were to hold the enemy out of Masan duringthe critical period ahead.

The N.K. 6th Division now took up defensive positionsopposite the 25th Division in the mountains west of Masan. It placed its13th Regiment on the left near the Nam River, the 15thin the center, and the 14th on the right next to the coast. Remnantsof the 83d Motorized Regiment continued to supportthe division. The first replacements for the 6th Division-2,000of them-arrived at Chinju reportedly on 12 August. Many of these were SouthKoreans from Andong, forced into service. They were issued hand grenadesand told to pick up arms on the battlefield. Prisoners reported that the6th Division was down to a strength of between 3,000-4,000men. Apparently it still had about twelve T34 tanks which needed fuel.The men had little food. All supplies were carried to the front by A-frame porters, there placed in dumps, and camouflagedwith leaves and grass. [50]

During the fighting between Task Force Kean and the N.K. 6thDivision on the Masan front, violent and alarming battles had eruptedelsewhere. Sister divisions of the N.K. 6th in the north along theNaktong were matching it in hard blows against Eighth Army's defense line.The battles of the Pusan Perimeter had started.

[1] EUSAK WD, PIR 21, 2 Aug 50 and 23, 4 Aug 50.

[2] 2 EUSAK WD, 4 Aug 50, Stf Study, G-3 Sec to the G-3.

[3] Ibid., Check Slip, 4 Aug 50, and Informal Check Slip, 5 Aug 50; Interv, author with Lt Col Paul F. Smith, 1 Oct 52.

[4] EUSAK WD, 5 Aug 50, Ltr, G-3 Air EUSAK to CG Fifth AF.

[5] Ibid., 6 Aug 50, G-3 Opn Directive and ans.

[6] 25th Div WD, Summ, Aug 50, p. 7; Ibid., 6-7 and 9 Aug 50. Total supported strength of the 25th Division is given as 23,080 troops, including 11,026 attached. This included the 27th Infantry Regiment, which became army reserve on 7 August. On 9 August this number had increased to 24,179, of which 12,197 were attached.

[7] 1st Prov Mar Brig, SAR, 2 Aug-6 Sep 50, pp. 1-19; 1st Bn, 5th Mar, SAR, Aug 50, p. 1.

[8] 25th Div WD, 6 Aug 50; 25th Div Opn Ord 8, 6 Aug 50.

[9] Ibid.; Barth MS, p. 13.

[10] EUSAK WD, 6 Aug 50, an. to Opn PIR.

[11] 25th Div WD, 6-7 Aug 50; 35th Inf WD, 7 Aug 50; Interv, author with Fisher, 5 Jan 52.

[12] 24th Div WD, 8-11 Aug 50; 35th Inf WD, 8-11 Aug 50; Barth MS, p. 14; Fisher, MS review comments, 7 Nov 57.

[13] 24th Inf WD, 6 Aug 50; EUSAK IG Rpt on 24th Inf, testimony of 1st Lt Christopher M. Gooch, S-3, 3d Bn, 24th Inf, 26 Aug 50. Department of the Army General Order 63, 2 August 1951, awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously to Pfc. William Thompson, M Company, 24th Infantry.

[14] Interv, author with Col John L. Throckmorton, 20 Aug 52; Throckmorton, MS review comments, 30 Mar 55.

[15] Ibid.; 5th Mar SAR, 6-7 Aug 50; Barth MS; New York Times, August 8, 1950, W. H. Lawrence dispatch from southern front; New York Herald Tribune, August 9, 1950, Homer Bigart dispatch from Korea, 7 August.

[16] 2d Bn, 5th Mar, SAR, 7 Jul-31 Aug 50, p. 6.

[17] 25th Div WD, 7 Aug 50; New York Herald Tribune, August 8, 1950, and August 9, 1950, Bigart dispatches; 1st Prov Mar Brig SAR, 2 Jul-6 Sep 50, p. 9; 27th Inf WD, Aug 50.

[18] 2d Bn, 5th Mar, SAR, 7 Jul-31 Aug 50, p. 6; Montross and Canzona, The Pusan Perimeter, pp. 16-17.

In a Marine infantry regiment, the 1st Battalion consisted of Headquarters and Service, A, B, C, and Weapons Companies; the 2d Battalion consisted of Headquarters and Service, D, E, F, and Weapons Companies; and the 3d Battalion consisted of Headquarters and Service, G, H, I, and Weapons Companies.

[19] 159th FA Bn WD, 7-9 Aug 50; 3d Bn, 5th Mar, SAR, Aug 50 (Rpt of 1st Pl, G Co); 5th Mar SAR, 8-9 Aug 50; 1st Prov Mar Brig SAR, 8-9 Aug 50, pp. 10-11; Montross and Canzona, The Pusan Perimeter, pp. 121-22; New York Herald Tribune, August 9, 1950, Bigart dispatch; Col Godwin Ordway, MS review comments, 21 Nov 57.

[20] Interv, author with Throckmorton, 20 Aug 52.

[21] 25th Div WD, 9 Aug 50.

[22] 1st Prov Mar Brig SAR, 10 Aug 50; 5th Mar SAR, 10 Aug 50; Ernest H. Giusti, "Marine Air Over the Pusan Perimeter," Marine Corps Gazette (May, 1952), pp. 20-21; New York Herald Tribune, August 10, 1950.

[23] 25th Div WD, 10 Aug 50; New York Times, August 10, 1950.

[24] 1st Prov Mar Brig SAR, Aug 50, p. 11; 5th Mar SAR, 11 Aug 50; 3d Bn, 5th Mar SAR, 11 Aug, p. 4; Giusti, op. cit.; Lt Col Ransom M. Wood, "Artillery Support for the Brigade in Korea," Marine Corps Gazette (June, 1951), p. 18; GHQ UNC G-3 Opn Rpt 49, 12 Aug 50; 25th Div WD, 11 Aug 50. Enemy troop casualties in this action were estimated at about 200.

[25] 1st Bn, 5th Mar SAR, 12 Aug 50; 1st Prov Mar Brig SAR, 12 Aug 50, p. 12; 5th Mar SAR, 12 Aug 50; Maj. Francis I. Fenton, Jr., "Changallon Valley," Marine Corps Gazette (November, 1951), pp. 4953; ATIS Supp, Enemy Docs, Issue 2, pp. 97-98, gives the North Korean order for the attack on Hill 202. The 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, gives its casualties for 12-13 August as 15 killed, 33 wounded, and 8 missing. Montross and Canzona, The Pusan Perimeter, page 155 give the Marine loss on Hill 202 in the night battle as 12 killed, 18 wounded, and 8 missing.

[26] Montross and Canzona, The Pusan Perimeter, page 148, quoting from General Craig's field notebook for 12 August 1950.

[27] Ltr with comments, Col Ordway to author, 18 Feb 55; Ltrs, Col John H. Daly to author, 3 Dec 54 and 11 Feb 55; Comments on Bloody Gulch, by Lt Col T. B. Roelofs, 15 Feb 55, copy furnished author by Col Ordway, 18 Feb 55. Despite an extensive search in the Departmental Records Section of the AC and elsewhere the author could not find the war diaries, journals, periodic reports, and other records of the 5th Regimental Combat Team and the 555th Field Artillery Battalion for August 1950.

[28] Ltr, Ordway to author, 18 Feb 55; Throckmorton, Notes for Ordway, 30 Mar 55 (forwarded by Ordway to author): Roelofs, Comments on Bloody Gulch, 15 Feb 55.

[29] Roelofs, Comments on Bloody Gulch, 15 Feb 55; Ltr and comments, Ordway to author, 18 Feb 55, and MS review comments, 21 Nov 57.

[30 Intervs, author with Ordway, 3 and 21 Jan 55; Ltr and comments, Ordway to author, 18 Feb 55; Ordway, MS review comments, 21 Nov 57, Roelofs, Comments on Bloody Gulch, 15 Feb 55; Ltr, Daly to author, 8 Dec 54. Roelofs and Daly confirm Ordway's account of his plan to move the regiment through the pass at night, and the division's order that all units except the 2d Battalion and C Battery, 555th Field Artillery Battalion, were to remain in position until daylight.

[31] 25th Div WD, 11 Aug 50; 88th Med Tk Bn WD, 7-31 Aug 50; EUSAK WD, G-3 Sec, 11 Aug 50; Ibid., POR 90, 11 Aug 50; Ltr, Lt Gen William B. Kean to author, 17 Jul 53.

[32] 25th Div WD, 12 Aug 50; 90th FA Bn WD, 11-12 Aug 50; 159th FA Bn WD, 11-12 Aug 50, and sketch 4.

[33] Roelofs, Comments on Bloody Gulch, 15 Feb 55.

[34] Intervs, author with Ordway, 3 and 21 Jan 55; Ltr, Ordway to author, 18 Feb 55; Ordway, MS review comments, 20 Nov 57.

[35] ATIS Supp, Enemy Docs, Issue 2, pp. 97-98, gives the enemy order for the attack at Bloody Gulch.

[36] 25th Div WD, 12 Aug 50; 90th FA Bn WD, 12 Aug 50; 159th FA Bn WD, 12 Aug 50; Barth MS, p. 17; Interv, Gugeler with Capt Perry H. Graves, CO, B Btry, 555th FA Bn, 9 Aug 51; Interv, author with 1st Lt Lyle D. Robb, CO, Hq Co, 5th Inf, 9 Aug 51; 1st Lt Wyatt Y. Logan, 555th FA Bn, Debriefing Rpt 64, 22 Jan 5:, FA School, Ft. Sill.

[37] 90th FA Bn WD, 11-21 Aug 50; Barth MS, p. 18. Department of the Army General Order 36, 4 June 1951, awarded the Distinguished Unit Citation to the 90th Field Artillery Battalion.

[38] 90th FA Bn WD, 12 Aug 50; Barth MS; New York Herald Tribune, August 12, 1950, Bigart dispatch.

[39] 159th FA Bn WD, 11-12 Aug 50. [40] General Order 232, 23 April 1951, awarded the Distinguished Service Cross posthumously to Sergeant Tedford. EUSAK WD.

[41] Interv, author with Throckmorton, 20 Aug 52.

[42] Barth MS, p. 19: 3d Bn, 24th Inf WD, 12 Aug 50; 25th Div WD, 12 Aug 50.

[43] 3d Bn, 5th Mar SAR, 12-13 Aug 50; 1st Prov Mar Brig SAR, 12-13 Aug 50; Montross and Canzona, The Pusan Perimeter, pp. 150-52.

[44] Interv, author with Corley, 6 Nov 51; Barth MS, p. 19; EUSAK IG Rpt, 24th Inf Regt, testimony of Corley, 26 Aug 50.

[45] 25th Div WD, 13 Aug 50; 90th FA Bn WD, 12 Aug 50; 27th Inf Narr Hist Rpt, Sep 50; Barth MS, p. 17; New York Herald Tribune, August 14, 1950, Bigart dispatch.

[46] 25th Div WD, 24 Sep 50; Barth MS, p. 17. In addition to its guns, the 90th lost 26 vehicles and 2 M5 tractors. The 555th lost practically all its vehicles. Many 1st Battalion and regimental headquarters vehicles were also destroyed or abandoned. The North Korean communiqué for 12 August, monitored in a rebroadcast from Moscow, claimed, in considerable exaggeration, 9 150-mm. guns, 12 105-mm. guns, 13 tanks, and 157 vehicles captured or destroyed. See New York Times, August 16, 1950: Barth MS, p. 21; Interv, author with Stuart, 9 Aug 51.

[47] Interv, author with Throckmorton, 20 Aug 52; Ordway, MS review comments, 20 Nov 57.

[48] Interv, author with Arnold, 22 Jul 51: Interv, author with Fisher, 2 Jan 52; Fisher, MS review comments, 7 Nov 57; Barth MS, p. 15.

[49] 25th Div WD, 16 Aug 50; GHQ UNC G-3 Opn Rpt 53, 16 Aug 50.[50] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 100 (N.K. 6th Div), pp. 38-39; 27th Inf WD, Aug 50, PW Rpt 10; EUSAK WD, 12 Aug 50, Interrog Rpt 519; 25th Div WD, Aug 50, PW Interrog.

|

|

- A VETERAN's Blog - |