|

|

CHAPTER XXStalemate West of Masan |

The Foundation of Freedom is the Courage of Ordinary PeopleHistory |

| In war events of importance are the result of trivial causes. |

| JULIUS CAESAR, Bellum Gallicum |

When enemy penetrations in the Pusan Perimeter at the bulge of the Naktongcaused General Walker to withdraw the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade fromTask Force Kean, he ordered the 25th Division to take up defensive positionson the army southern flank west of Masan. By 15 August the 25th Divisionhad moved into these positions.

The terrain west of Masan dictated the choice of the positions. Themountain barrier west of Masan was the first readily defensible groundeast of the Chinju pass. (See Map IV.) The two thousand-footmountain ridges of Sobuk-san and P'il-bong dominated the area and protectedthe Komam-ni (Saga)-Haman-Chindong-ni road, the only means of north-southcommunication in the army zone west of Masan.

Northward from the Masan-Chinju highway to the Nam River there werea number of possible defensive positions. The best one was the Notch andadjacent high ground near Chungam-ni, which controlled the important roadjunction connecting the Masan road with the one over the Nam River to Uiryong.This position, however, had the disadvantage of including a 15-mile stretchof the Nam River to the point of its confluence with the Naktong, thusgreatly lengthening the line. It was mandatory that the 25th Division rightflank connect with the left flank of the 24th Division at the confluenceof the Nam and the Naktong Rivers. Within this limitation, it was alsonecessary that the 25th Division line include and protect the Komam-niroad intersection where the Chindong-ni-Haman road met the Masan-Chinjuhighway.

From Komam-ni a 2-mile-wide belt of rice paddy land extended north fourmiles to the Nam River. On the west of this paddy land a broken spur ofP'il-bong, dominated by 900-foot-high Sibidang-san, dropped down to theNam. Sibidang provided excellent observation, and artillery emplaced inthe Komam-ni area could interdict the road junction at Chungam-ni. ColonelFisher, therefore, selected the Sibidang-Komam-ni position for his 35thInfantry Regiment in the northern part of the 25th Division defense line.The 35th Regiment line extended from a point two miles west of Komam-ni to the Nam River and then turned east along that stream toits confluence with the Naktong. It was a long regimental line-about 26,000yards. [1]

The part of the line held by the 35th Infantry-covering as it did themain Masan-Chinju highway, the railroad, and the Nam River corridor, andforming the hinge with the 24th Division to the north-was potentially themost critical and important sector of the 25th Division front. Lt. Col.Bernard G. Teeter's 1st Battalion held the regimental left west of Komam-ni;Colonel Wilkins' 2d Battalion held the regimental right along the Nam River.Maj. Robert L. Woolfolk's 3d Battalion (1st Battalion, 29th Infantry) wasin reserve on the road south of Chirwon from where it could move quicklyto any part of the line.

South of the 35th Infantry, Colonel Champney's 24th Infantry, knownamong the men in the regiment as the "Deuce-Four," took up themiddle part of the division front in the mountain area west of Haman.

Below (south) the 24th Infantry and west of Chindong-ni, Colonel Throckmorton's5th Regimental Combat Team was on the division left. On division orders,Throckmorton at first held the ground above the Chindong-ni coastal roadonly as far as Fox Hill, or Yaban-san. General Kean soon decided, however,that the 5th Regimental Combat Team should close the gap northward betweenit and the 24th Infantry. When Throckmorton sent a ROK unit of 100 menunder American officers to the higher slope of Sobuk-san, enemy troopsalready there drove them back. General Kean then ordered the 5th RegimentalCombat Team to take this ground, but it was too late. [2]

1stIn front of the 25th Division, the N.K. 6th Divisionhad now received orders from the North Korean command to take up defensivepositions and to await reinforcements before continuing the attack. [3]From north to south, the division had its 13th, 15th, and14th Regiments on line in that order. The first replacementsfor the division arrived at Chinju on or about 12 August. Approximately2,000 unarmed South Koreans conscripted in the Seoul area joined the divisionby 15 August. At Chinju, the 6th Division issued them grenadesand told the recruits they would have to pick up weapons from killed andwounded on the battlefield and to use captured ones. A diarist in thisgroup records that he arrived at Chinju on 13 August and was in combatfor the first time on 19 August. Two days later he wrote in his diary,"I am much distressed by the pounding artillery and aerial attacks.We have no food and no water, we suffer a great deal.... I am on a hillclose to Masan." [4]

Another group of 2,500 replacements conscripted in the Seoul area joinedthe 6th Division on or about 21 August, bringing the divisionstrength to approximately 8,500 men. In the last week of August and the first week of September, 3,000 more recruits conscriptedin southwest Korea joined the division. The 6th Divisionused this last body of recruits in labor details at first and only lateremployed them as combat troops. [5]

As a part of the enemy build-up in the south, another division now arrivedthere-the 7th Division. This division was activated on 3July 1950; its troops included 2,000 recruits and the 7th BorderConstabulary Brigade of 4,000 men. An artillery regimenthad joined this division at Kaesong near the end of July. In Seoul on 30July, 2,000 more recruits conscripted from South Korea brought the 7thDivision's strength to 10,000. The division departed Seoul on 1August, the men wading the neck-deep Han River while their vehicles andheavy weapons crossed on the pontoon bridge, except for the division artillerywhich was left behind. The 7th Division marched south throughTaejon, Chonju, and Namwon. The 1st and 3d Regimentsarrived at Chinju on or about 15 August. Two days later some elements ofthe division reached T'ongyong at the southern end of the peninsula, twenty-fiveair miles southwest of Masan. The 2d Regiment arrived atYosu on or about 15 August to garrison that port. The 7th Division,therefore, upon first arriving in southwest Korea occupied key ports toprotect the 6th Division against possible landings in itsrear. [6]

The reinforced battalion that had driven the ROK police out of T'ongyongdid not hold it long. U.N. naval forces heavily shelled T'ongyong on 19August as three companies of ROK marines from Koje Island made an amphibiouslanding near the town. The ROK force then attacked the North Koreans and,supported by naval gun fire, drove them out. The enemy in this action atT'ongyong lost about 350 men, or about half their reinforced battalion;the survivors withdrew to Chinju.

By 17 August, the reinforced North Koreans had closed on the 25th Divisiondefensive line and had begun a series of probing attacks that were to continuethroughout the month. What the N.K. 6th Division called "aggressivepatrolling" soon became, in the U.S. 24th and 35th Infantry sectors,attacks of company and sometimes of battalion strength. Most of these attackscame in the high mountains west of Haman, in the Battle Mountain, P'il-bong,and Sobuk-san area. There the 6th Division seemed peculiarlysensitive where any terrain features afforded observation of its supplyand concentration area in the deeply cut valley to the west.

It soon became apparent that the enemy 6th Division hadshifted its axis of attack and that its main effort now would be in thenorthern part of the Chinju-Masan corridor just below the Nam River. GeneralKean had placed his strongest regiment, the 35th Infantry, in this area.Competent observers considered its commanding officer, Colonel Fisher,one of the ablest regimental commanders in Korea. Calm, somewhat retiring, ruddy faced, and possessedof a strong, compact body, this officer was a fine example of the professionalsoldier. He possessed an exact knowledge of the capabilities of the weaponsused in an infantry regiment and was skilled in their use. He was a technicianin the tactical employment of troops. Of quiet temperament, he did notcourt publicity. One of his fellow regimental commanders called him "themainstay of the division." [8]

The 35th Infantry set to work to cover its front with trip flares, butthey were in short supply and gradually it became impossible to replacethose tripped by the enemy. As important to the front line companies asthe flares were the 60-mm. mortar illuminating shells. This ammunitionhad deteriorated to such a degree, however, that only about 20 percentof the supply issued to the regiment was effective. The 155-mm. howitzerilluminating shells were in short supply. Even when employed, the timelapse between a request for them and delivery by the big howitzers allowedsome enemy infiltration before the threatened area was illuminated. [9]

Lt. Col. Arthur H. Logan's 64th Field Artillery Battalion, with C Battery,90th Field Artillery Battalion, attached, and Captain Harvey's A Company,88th Medium Tank Battalion, supported Colonel Fisher's regiment. Threemedium M4A3 tanks, from positions at Komam-ni, acted as artillery and placedinterdiction fire on Chungam-ni. Six other medium M26 tanks in a similarmanner placed interdiction fire on Uiryong across the Nam River. [10]

In the pre-dawn hours of 17 August an enemy attack got under way againstthe 35th Infantry. North Korean artillery fire began falling on the 1stBattalion command post in Komam-ni at 0300, and an hour later enemy infantryattacked A Company, forcing two of its platoons from their positions, andoverrunning a mortar position. After daylight, a counterattack by B Companyregained the lost ground. This was the beginning of a 5-day battle by ColonelTeeter's 1st Battalion along the southern spurs of Sibidang, two mileswest of Komam-ni. The North Koreans endeavored there to turn the left flankof the 35th Regiment and split the 25th Division line. On the morning of18 August, A Company again lost its position to enemy attack and againregained it by counterattack. Two companies of South Korean police arrivedto reinforce the battalion right flank. Against the continuing North Koreanattack, artillery supporting the 1st Battalion fired an average of 200rounds an hour during the night of 19-20 August. [11]

After three days and nights of this battle, C Company of the 35th Infantryand A Company of the 29th Infantry moved up astride the Komam-ni road duringthe morning of 20 August to bolster A and B Companies on Sibidang. Whilethis reinforcement was in progress, Colonel Fisher from a forward observation post saw a large enemyconcentration advancing to renew the attack. He directed artillery fireon this force and called in an air strike. Observers estimated that theartillery fire and the air strike killed about 350 enemy troops, half theattack group. [12]

The North Koreans made still another try in the same place. In the pre-dawnhours of 22 August, enemy infantry started a very heavy attack againstthe 1st Battalion. Employing no artillery or mortar preparatory fires,the enemy force in the darkness cut the four-strand barbed wire and attackedat close quarters with small arms and grenades. This assault engaged threeAmerican companies and drove one of them from its position. After threehours of fighting A Company counterattacked at 0700 and regained its lostposition. The next day, 23 August, the North Koreans, frustrated in thisarea, withdrew from contact in the 35th Infantry sector. [13]

At the same time that the North Koreans were trying to penetrate the35th Infantry positions in the Sibidang-Komam-ni area, they sent strongpatrols and probing attacks against the mountainous middle part of the25th Division line. Since this part of the division line became a continuingproblem in the defense of the Perimeter, more should be said about theterrain there and some of its critical features.

Old mine shafts and tunnels on the western slope of Sobuk-san providedthe North Koreans in this area with ready-made underground bunkers, assemblypoints, and supply depots. As early as the first week of August, the NorthKoreans were in this mountain fastness and had never been driven out. Itwas the assembly area for their combat operations on the Masan front allduring the month. Even when American troops had held the Notch positionbeyond Chungam-ni, their combat patrols had never been able to penetratealong the mountain trail that branches off the Masan road and twists itsway up the narrow mountain valley to the mining villages of Ogok and Tundok,at the western base of Battle Mountain and P'ilbong, two peaks of Sobuk-san.The patrols always were either ambushed or driven back by enemy action.The North Koreans firmly protected all approaches to their Sobuk-san stronghold.[14]

When the 25th Division issued orders to its subordinate units to takeup defensive positions west of Masan, the 2d Battalion, 24th Infantry,was still trying to seize Obong-san, the mountain ridge just west of BattleMountain and P'il-bong, and across a gorgelike valley from them. At daybreakof 15 August, the 2d Battalion broke contact with the enemy and withdrewto Battle Mountain and the ridge west of Haman. The 3d Battalion of the24th Infantry now came to the Haman area to help in the regimental defenseof this sector. [15]

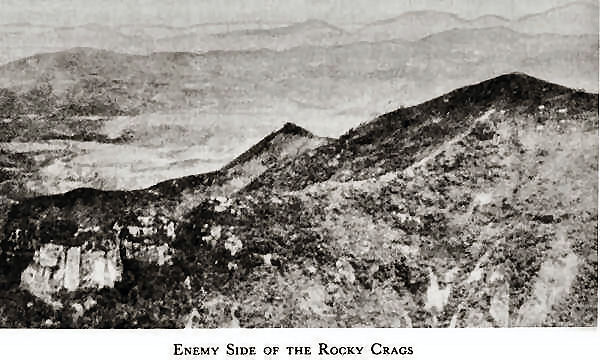

This high ground west of Haman on which the 24th Infantry established its defensive line was part of theSobuk-san mountain mass. Sobuk-san reaches its highest elevation, 2,400feet, at P'il-bong (Hill 743), eight miles northwest of Chindong-ni andthree miles southwest of Haman. From P'il-bong the crest of the ridge linedrops and curves slightly northwestward, to rise again a mile away in thebald peak which became known as Battle Mountain (Hill 665). It also wasvariously known as Napalm Hill, Old Baldy, and Bloody Knob. Between P'il-bongand Battle Mountain the ridge line narrows to a rocky ledge which the troopscalled the Rocky Crags. Northward from Battle Mountain toward the Nam River,the ground drops sharply in two long spur ridges. Men who fought therecalled the eastern one Green Peak. [16]

At the western base (enemy side) of Battle Mountain and P'il-bong layOgok and Tundok, one and a quarter air miles from the crest. A generallynorth-south mountain road-trail crossed a high saddle just north of thesevillages and climbed to the 1,100-foot level of the west slope, or abouthalfway to the top, of Battle Mountain. This road gave the North Koreansan advantage in mounting and supplying their attacks in this area. A trailsystem ran from Ogok and Tundok to the crests of Battle Mountain and P'il-bong.From the top of Battle Mountain an observer could look directly down intothis enemy-held valley, upon its mining villages and numerous mine shafts.Conversely, from Battle Mountain the North Koreans could look down intothe Haman valley eastward and keep the 24th Infantry command post, supplyroad, artillery positions, and approach trails under observation. Whicheverside held the crest of Battle Mountain could see into the rear areas ofthe other. Both forces fully understood the advantages of holding the crestof Battle Mountain and each tried to do it in a 6-week-long battle.

The approach to Battle Mountain and P'il-bong was much more difficultfrom the east, the American-held side, than from the west, the North Koreanside. On the east side there was no road climbing halfway to the top; fromthe base of the mountain at the edge of the Haman valley the only way tomake the ascent was by foot trail. Stout climbers required from 2 to 3hours to reach the top of P'il-bong from the reservoir area, one and ahalf air miles eastward; they required from 3 to 4 hours to get on topof Battle Mountain from the valley floor. The turnaround time for porterpack trains to Battle Mountain was 6 hours. Often a dispatch runner required8 hours to go up Battle Mountain and come back down. In some places thetrail was so steep that men climbed with the help of ropes stretched atthe side of the trail. Enemy night patrols constantly cut telephone lines.The wire men had a difficult and dangerous job trying to maintain wirecommunication with units on the mountain.

Bringing dead and seriously wounded down from the top was an arduoustask. It required a litter bearer team of six men to carry a wounded manon a stretcher down the mountain. In addition, a medical aide was neededto administer medical care during the trip if the man was critically wounded,and riflemen often accompanied the party to protect it from enemy snipersalong the trail. A critically wounded man might, and sometimes did, diebefore he reached the bottom where surgical and further medical care couldbe administered. This possibility was one of the factors that lowered moralein the 24th Infantry units fighting on Battle Mountain. Many men were afraidthat if they were wounded there they would die before reaching adequatemedical care. [17]

In arranging the artillery and mortar support for the 24th Infantryon Battle Mountain and P'il-bong, Colonel Champney placed the 4.2-inchmortars and the 159th Field Artillery Battalion in the valley south ofHaman. On 19 August the artillery moved farther to the rear, except forC Battery, which remained in the creek bed north of Haman at Champney'sinsistence. Champney in the meantime had ordered his engineers to improvea trail running from Haman northeast to the main Komam-ni-Masan road. Heintended to use it for an evacuation road by the artillery, if that becamenecessary, and to improve the tactical and logistical road net of the regimentalsector. This road became known as the Engineer Road. [18]

When Colonel Champney on 15 August established his line there was a4,000-yard gap in the P'il-bong area between the 24th Infantry and the5th Infantry southward. The 24th Infantry had not performed well duringthe Task Force Kean action and this fact made a big gap adjacent to ita matter of serious concern. General Kean sent 432 ROK National Policeto Champney the next day and the latter placed them in this gap. [19]

The first attack against the mountain line of the 24th Infantry cameon the morning of 18 August, when the enemy partly overran E Company onthe northern spur of Battle Mountain and killed the company commander.During the day, Lt. Col. Paul F. Roberts succeeded Lt. Col. George R. Colein command of the 2d Battalion there. The next day, the enemy attackedC Company on Battle Mountain and routed it. Officers could collect onlyforty men to bring them back into position. Many ROK police on P'il-bongalso ran away-only fifty-six of them remained in their defensive positions.American officers used threats and physical force to get others back intoposition. A gap of nearly a mile in the line north of P'il-bong existedin the 24th Infantry lines at the close of the day, and an unknown numberof North Koreans were moving into it. [20]

On to August, all of C Company except the company commander and abouttwenty-five men abandoned their position on Battle Mountain. Upon reachingthe bottom of the mountain those who had fled reported erroneously thatthe company commander had been killed and their position surrounded, thenover-run by the enemy. On the basis of this misinformation, American artilleryand mortars fired concentrations on C Company's former position, and fighter-bombers,in thirty-eight sorties, attacked the crest of Battle Mountain, using napalm,fragmentation bombs, rockets, and strafing. This friendly action, basedupon completely erroneous reports, forced the company commander and hisremnant of twenty-five men off Battle Mountain after they had held it fornearly twenty hours. A platoon of E Company, except for eight or ten men,also left its position on the mountain under similar circumstances. Onthe regimental left, a ROK patrol from K Company's position on Sobuk-sanhad the luck to capture the commanding officer of the N.K. 15thRegiment but, unfortunately, he was killed a few minutes later whiletrying to escape. The patrol removed important documents from his body.And on this day of general melee along Battle Mountain and P'il-bong, theNorth Koreans drove off the ROK police from the 24th Infantry's left flankon Sobuk-san. [21]

General Kean now alerted Colonel Throckmorton to prepare a force fromthe 5th Infantry to attack Sobuk-san. On the morning of 21 August, the1st Battalion (less A Company), 5th Regimental Combat Team, attacked acrossthe 24th Infantry boundary and secured Sobuk-san against light resistance.That evening a strong force of North Koreans counterattacked and drovethe 1st Battalion off the mountain. At noon the next day, the 1st Battalionagain attacked the heights, and five hours later B Company seized the peak.General Kean now changed the boundary line between the 5th Regimental CombatTeam and the 24th Infantry, giving the Sobuk-san peak to the former. Duringthe night, the North Koreans launched counterattacks against the 1st Battalion,5th Regimental Combat Team, and prevented it from consolidating its position.On the morning of 23 August, A Company tried to secure the high ground1,000 yards southwest of Sobuk and link up with B Company, but was unableto do so. The enemy considered this particular terrain feature so importantthat he continued to repulse all efforts to capture it, and kept A Company,5th Regimental Combat Team, nearby, under almost daily attack. [22]

Northward from B Company's position on Sobuk, the battle situation wassimilar. Enemy troops in the Rocky Crags, which extended from Sobuk-santoward P'il-bong, took cover during air strikes, and napalm, 500-poundbombs, and strafing had little effect. As soon as the planes departed theyreoccupied their battle positions. Elements of the 24th Infantry were notable to extend southward and join with B Company of the 5th RegimentalCombat Team. [23]

Still farther northward along the mountain spine, in the Battle Mountainarea, affairs were going badly for the 24th Infantry. After C Company lost Battle Mountain, air and artilleryworked over its crest in preparation for an infantry attack planned toregain Old Baldy. The hot and sultry weather made climbing the steep slopegrueling work, but L Company was on top by noon, 21 August. Enemy troopshad left the crest under the punishing fire of air, artillery, and mortar.They in turn now placed mortar fire on the crest and prevented L Companyfrom consolidating its position. This situation continued until midafternoonwhen an enemy platoon came out of zigzag trenches a short distance downthe reverse slope of Old Baldy and surprised L Company. One enemy soldiereven succeeded in dropping a grenade in a platoon leader's foxhole. Theother two platoons of the company, upon hearing firing, started to leavetheir positions and drift down the hill. The North Koreans swiftly reoccupiedOld Baldy while officers tried to assemble L and I Companies on the easternslope. Elements of E Company also left their position during the day. [24]

American air, artillery, mortar, and tank fire now concentrated on BattleMountain, and I and L Companies prepared to counterattack. This attackmade slow progress and at midnight it halted to wait for daylight. Shortlyafter dawn, 22 August, I and L Companies resumed the attack. Lt. R. P.Stevens led L Company up the mountain, with I Company supplying a baseof fire. Lt. Gerald N. Alexander testified that, with no enemy fire whatever,it took him an hour to get his men to move 200 yards. When they eventually reached their objective,three enemy grenades wounded six of then, and at this his group ran offthe hill. Alexander stopped them 100 yards down the slope and ordered themto go back up. None would go. Finally, he and a BAR man climbed back andfound no defending enemy on the crest. His men slowly rejoined him. Theremainder of the company reached the objective on Battle Mountain witha total loss of 17 casualties in three hours' time. A few hours later,when a small enemy force worked around its right flank, the company withdrewback down the hill to I Company's position. [25]

Fighting continued on Battle Mountain the next day, 23 August, withROK police units arriving to reinforce I and L Companies. The Americanand South Korean troops finally secured precarious possession of Old Baldy,mainly because of the excellent supporting fires of the 81-mm. and 4.2-inchmortars covering the enemy's avenues of approach on the western slope.Before its relief on the mountain, L Company reported a foxhole strengthof 17 men, yet, halfway down the slope, its strength had jumped to 48 men,and by the next morning it was more than 100. Colonel Corley, in commandof the 3d Battalion, 24th Infantry, said, "Companies of my battaliondwindle to platoon size when engaged with the enemy. My chain of commandstops at company level. If this unit is to continue to fight as a battalionit is recommended that the T/O of officers be doubled. One officer mustlead and the other must drive." The situation in the Haman area causedGeneral Walker to alert the Marine brigade for possible movement to thispart of the front. [26]

On 25 and 26 August, C Company beat off a number of North Korean thrustson Battle Mountain-all coming along one avenue of approach, the long fingerridge extending upward from the mines at Tundok. At one point in this seriesof actions, a flight of Air Force planes caught about 100 enemy soldiersin the open and immediately napalmed, bombed, and strafed them. There werefew survivors. Task Force Baker, commanded by Colonel Cole, and comprisingC Company, a platoon of E Company, 24th Infantry, and a ROK police company,defended Battle Mountain at this time. The special command was establishedbecause of the isolated Battle Mountain area and the extended regimentalbattle frontage. It buried many enemy dead killed within or in front ofits positions during these two days. [27]

The 3d Battalion, 24th Infantry, now relieved the 1st Battalion in theBattle Mountain-P'il-bong area, except for C Company which, as part ofTask Force Baker, remained on Old Baldy. Corley's battalion completed thisrelief by 1800, 27 August. [28]

The North Korean attacks continued. On the 28th, an enemy company-sized attack struck between C and I Companies before dawn. That night, enemymortar fire fell on C Company on Old Baldy, some of it obviously directedat the company command post. After midnight, an enemy force appeared inthe rear area and captured the command post. Some men of C Company lefttheir positions on Battle Mountain when the attack began at 0245, 29 August.The North Koreans swung their attack toward E Company and overran partof its positions. Airdrops after daylight kept C Company supplied withammunition, and a curtain of artillery fire, sealing off approaches fromthe enemy's main position, prevented any substantial reinforcement fromarriving on the crest. All day artillery fire and air strikes pounded theNorth Koreans occupying E Company's old positions. Then, in the evening,E Company counterattacked and reoccupied the lost ground. [33]

An hour before midnight, North Koreans attacked C Company. Men on theleft flank of the company position jumped from their holes and ran downthe mountain yelling, "They have broken through!" The panic spread.Again the enemy had possession of Battle Mountain. Capt. Lawrence M. Corcoran,the company commander, was left with only the seventeen men in his commandpost, which included several wounded. [30] After daylight on the 30th,air strikes again came in on Battle Mountain, and artillery, mortar, andtank fire from the valley concentrated on the enemy-held peak. A woundedman came down off the mountain where, cut off, he had hidden for severalhours. He reported that the main body of the North Koreans had withdrawnto the wooded ridges west of the peak for better cover, leaving only asmall covering force on Old Baldy itself. At 1100, B Company, with the3d Battalion in support, attacked toward the heights and two hours laterwas on top. [31]

Units of the 24th Infantry always captured Battle Mountain in the sameway. Artillery, mortar, and tank fire raked the crest and air strikes employingnapalm blanketed the scorched top. Then the infantry attacked from thehill beneath Old Baldy on the east slope, where supporting mortars setup a base of fire and kept the heights under a hail of steel until theinfantry had arrived at a point just short of the crest. The mortar firethen lifted and the infantry moved rapidly up the last stretch to the top,usually to find it deserted by the enemy. [32]

Battle Mountain changed hands so often during August that there is noagreement on the exact number of times. The intelligence sergeant of the1st Battalion, 24th Infantry, said that according to his count the peakchanged hands nineteen time. [33] From 18 August to the end of the month,scarcely a night passed that the North Koreans did not attack Old Baldy. The peak often changed hands two or three times in a 24-hourperiod. The usual pattern was for the enemy to take it at night and the24th Infantry to recapture it the next day. This type of fluctuating battleresulted in relatively high losses among artillery forward observers andtheir equipment. During the period of 15-31 August, seven forward observersand eight other members of the Observer and Liaison Section of the 159thField Artillery Battalion, supporting the 24th Infantry, were casualties;and they lost 8 radios, 11 telephones, and 2 vehicles to enemy action.[34]

In its defense of that part of Sobuk-san south of Battle Mountain andP'ilbong, the 1st Battalion, 5th Regimental Combat Team, also had nearlycontinuous action in the last week of the month. MSgt. Melvin O. Handrichof C Company, 5th Regimental Combat Team, on 25 and 26 August distinguishedhimself as a heroic combat leader. From a forward position he directedartillery fire on an attacking enemy force and at one point personallykept part of the company from abandoning its positions. Although wounded,Sergeant Handrich returned to his forward position, to continue directingartillery fire, and there alone engaged North Koreans until he was killed.When the 5th Regimental Combat Team regained possession of his corner "ofa foreign field" it counted more than seventy dead North Koreans inthe vicinity. [35]

The month of August ended with the fighting in the mountain's on thesouthern front, west of Masan, a stalemate. Neither side had secured adefinite advantage. The 25th Division had held the central part of itsline, at Battle Mountain and Sobuk-san, only with difficulty and with mountingconcern for the future.

[1] 35th Inf Unit Hist, Aug 50.

[2] Interv, author with Throckmorton, 20 Aug 52: Throckmorton, Notes for author, 17 Apr 53.

[3] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 100 (N.K. 6th Div), pp. 37-38.

[4] Ibid., p. 38; ATIS Interrog Rpts, Issue 2, Rpt 712, p. 31, Chon Kwan O; ATIS Supp Enemy Docs, Issue 2, p. 70, Diary of Yun Hung Xi, 25 Jul-21 Aug 50.

[5] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 100 (N.K. 6th Div), p. 38.

[6] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 99 (N.K. 7th Div), p. 34; ATIS Interrog Rpts, Issue 2, p. 94, Capt So Won Sok, 7th Div.

[7] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 99 (N.K. 7th Div), pp. 34-35; ATIS Interrog Rpts, Issue 2, p. 94, Capt So; GHQ FEC G-3 Opn Rpt 57, 20 Aug 50; New York Times, August 21, 1950.

[8] Interv, author with Corley, 6 Nov 51; Interv, author with Throckmorton, 20 Aug 52 Interv, author with Brig Gen Arthur S. Champney, 22 Jul 51. Throckmorton and Champney agreed substantially with Corley's opinion.

[9] 1st Bn, 35th Inf WD, 14-31 Aug 50, Summ of Supply Problem.

[10] 35th Inf WD, 14-31 Aug 50: 88th Med Tank Bn WD, 16-17 Aug 50.

[11] 35th Inf WD, 17-20 Aug 50; 1st Bn, 35th Inf WD, 19 Aug 50.

[12] 1st Bn, 35th Inf WD, 20 Aug 50; 25th Div WD, 20 Aug 50.

[13] 35th Inf WD, 22 Aug 50; 25th Div WD, 23 Aug 50.

[14] Interv, author with Fisher, 5 Jan 52: 159th FA Bn WD, 12-15 Aug 50; 1st Bn, 24th Inf WD, 15 Aug 50.

[15] 2d Bn, 24th Inf WD, 15 Aug 50; 25th Div WD, 15 Aug 50.

[16] Interv, author with 1st Lt Louis M. Daniels, 2 Sep 51 (CO I&R Plat, 24th Inf, and during the Aug 50 action was a MSgt (Intel Sgt) in the 1st Bn, 24th Inf); Interv, author with Corley, 4 Jan 52 (Corley in Aug 50 was CO, 3d Bn, 24th Inf; in September of that year he became the regimental commander); AMS Map, Korea, 1:50,000.

[17] Interv, author with Corley, 4 Jan 52; Interv, author with Daniels, 2 Sep 51; Interv, author with Champney, 22 Jul 51; 24th Inf WD, 1-31 Aug 50, Special Problems and Lessons.

[18] Interv, author with Champney, 22 Jul 51; 159th FA Bn WD, Aug 50, and sketch maps 5 and 6.

[19] Col William 0. Perry, EUSAK IG Rpt, 24th Inf Regt, 1950, testimony of Capt Alfred F. Thompson, Arty Line Off with 24th Inf, 24 Aug 50; 24th Inf WD, 15-16 Aug 50.

[20] 1st Bn, 24th Inf WD, 19 Aug 50; 159th FA Bn WD, 19 Aug 50.

[21] 24th Inf WD, 20 Aug 50; 3d Bn, 24th Inf WD, 20 Aug 50; EUSAK IG Rpt, 24th Inf. testimony of Maj Eugene J. Carson, Ex Off, 2d Bn, 24th Inf, answer to question 141, 14 Sep 50; Ibid., statement of Capt Merwin J. Camp, 9 Sep 50.

[22] Interv, author with Throckmorton. 20 Aug 52; Throckmorton, Notes and sketch maps, 17 Apr 53; 25th Div WD, 21-24 Aug 50; EUSAK WD, G-3 Sec, 21-22 Aug 50; Ibid., 23 Aug 50.

[23] 1st Bn, 24th Inf WD, 23 Aug 50: Corley, Notes for author, 27 Jul 53. The code name King I was given to this rocky ledge extending from P'il-bong south toward Sobuk-san. See 159th FA Bn WD, 19 Aug 50.

[24] Corley, notes for author, 27 Jul 53: Interv, author with Corley, 4 Jan 52; EUSAK IG Rpt, 24th Inf Regt, 1950, testimony of 2d Lt Gerald N. Alexander, L Co, 24th Inf, 2 Sep 50; Ibid., testimony of Maj Horace E. Donaho, Ex Off, 2d Bn, 24th Inf, 22 Aug 50; 24th Inf WD, 21 Aug 50; EUSAK WD, G-3 Sec, 21 Aug 50.

[25] Interv, author with Corley, 4 Jan 52; EUSAK WD, G-3 Sec, 22 Aug 50; Ibid., Summ, 22 Aug 50; EUSAK IG Rpt, 24th Inf Regt, 1950, testimony of Corley, 26 Aug 50, and testimony of Alexander, 2 Sep 50.

[26] 24th Inf WD, 24 Aug 50; Interv, author with Corley, 4 Jan 52; EUSAK IG Rpt, 24th Inf Regt, 1950, testimony of Alexander, 2 Sep 50, and testimony of Corley, 26 Aug 50.

[27] 1st Bn, 24th Inf WD, 26 Aug 50; 24th Inf WD, 26 Aug 50; 24th Div WD, 26 Aug 50.

[28] 3d Bn, 24th Inf WD, 27 Aug 50; 25th Div WD, 27 Aug 50.

[29] 24th Inf WD, 29 Aug 50.

[30] Ibid.; 25th Div WD, 29 Aug 50; EUSAK IG Rpt, 24th Inf Div, 1950, testimony of Corcoran, 1 Sep 50. Corcoran said fire discipline in his company was very poor, that his men would fire at targets out of range until they had exhausted their ammunition and at night would fire when there were no targets. He said that in his entire company he had twenty-five men he considered soldiers and that they carried the rest.

[31] 24th Inf WD, 30 Aug 50; 25th Div WD, 30 Aug 50.

[32] Interv, author with Corley, 4 Jan 52.

[33] Interv, author with Daniels, 2 Sep 51.

[34] 159th FA Bn WD, 1-31 Aug 50.

[35] Department of the Army General Order 60, 2 August 1951 awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously to Sergeant Handrich.

|

|

- A VETERAN's Blog - |