|

|

CHAPTER XXVThe Breakthrough at Inchon |

The Foundation of Freedom is the Courage of Ordinary PeopleHistory |

| The history of war proves that nine out of ten times an army has beendestroyed because its supply lines have been cut off.... We shall landat Inch'on, and I shall crush them [the North Koreans]. |

| DOUGLAS MACARTHUR |

It was natural and predictable that General MacArthur should think interms of an amphibious landing in the rear of the enemy to win the KoreanWar. His campaigns in the Southwest Pacific in World War II-after Bataan-allbegan as amphibious operations. From Australia to Luzon his forces oftenadvanced around enemy-held islands, one after another. Control of the seasgives mobility to military power. Mobility and war of maneuver have alwaysbrought the greatest prizes and the quickest decisions to their practitioners.A water-borne sweep around the enemy's flank and an attack in his rearagainst lines of supply and communications appealed to MacArthur's senseof grand tactics. He never wavered from this concept, although repeatedlythe fortunes of war compelled him to postpone its execution.

During the first week of July, with the Korean War little more thana week old, General MacArthur told his chief of staff, General Almond,to begin considering plans for an amphibious operation designed to strikethe enemy center of communications at Seoul, and to study the locationfor a landing to accomplish this. At a Far East Command headquarters meetingon 4 July, attended by Army, Navy, and Air Force representatives, GeneralsMacArthur and Almond discussed the idea of an amphibious landing in theenemy's rear and proposed that the 1st Cavalry Division be used for thatpurpose. Col. Edward H. Forney of the Marine Corps, an expert on amphibiousoperations, was selected to work with the 1st Cavalry Division on plansfor the operation. [1]

The early plan for the amphibious operation received the code name BLUEHEARTSand called for driving the North Koreans back across the 38th Parallel.The approximate date proposed for it was 22 July, but the operation was abandoned by 10 July because of theinability of the U.S. and ROK forces in Korea to halt the southward driveof the enemy. [2]

Meanwhile the planning for an amphibious operation went ahead in theFar East Command despite the cancellation of BLUEHEARTS. These plans wereundertaken by the Joint Strategic Plans and Operations Group (JSPOG), FarEast Command, which General Wright headed in addition to his duties asAssistant Chief of Staff, G-3. One of Wright's deputies, Col. Donald H.Galloway, was directly in charge of JSPOG. This unusually able group ofplanners developed various plans in considerable detail for amphibiousoperations in Korea.

On 23 July, General Wright upon MacArthur's instructions circulatedto the GHQ staff sections the outline of Operation CHROMITE. CHROMITE calledfor an amphibious operation in September and postulated three plans: (1)Plan 100-B, landing at Inch'on on the west coast; (2) Plan 100-C, landingat Kunsan on the west coast; (3) Plan 100-D, landing near Chumunjin-upon the east coast. Plan 100-B, calling for a landing at Inch'on with asimultaneous attack by Eighth Army, was favored. [3]

This same day, 23 July, General MacArthur informed the Department ofthe Army that he had scheduled for mid-September an amphibious landingof the 5th Marines and the 2d Infantry Division behind the enemy's linesin co-ordination with an attack by Eighth Army. [4]

The North Korean successes upset MacArthur's plans as fast as he madethem. He admitted this to the Joint Chiefs in a message on 29 July, saying,"In Korea the hopes that I had entertained to hold out the 1st MarineDivision [Brigade] and the 2d Infantry Division for the enveloping counterblow have not been fulfilled and it will be necessary to commit these unitsto Korea on the south line rather than . . . their subsequent commitmentalong a separate axis in mid-September.... I now plan to commit my solereserve in Japan, the 7th Infantry Division, as soon as it can be broughtto an approximate combat strength." [5]

By 20 July General MacArthur had settled rather definitely on the conceptof the Inch'on operation and he spoke of the matter at some length withGeneral Almond and with General Wright, his operations officer. On 12 August,MacArthur issued CINCFE Operation Plan 100-B and specifically named theInch'on-Seoul area as the target that a special invasion force would seizeby amphibious assault. [6]

On 15 August General MacArthur established the headquarters group of the Special Planning Staff to takecharge of the projected amphibious operation. For purposes of secrecy thenew group, selected from the GHQ FEC staff, was designated, Special PlanningStaff, GHQ, and the forces to be placed under its control, GHQ Reserve.On 21 August, MacArthur requested the Department of the Army by radio forauthority to activate Headquarters, X Corps, and, upon receiving approval,he issued GHQ FEC General Order 24 on 26 August activating the corps. Allunits in Japan or en route there that had been designated GHQ Reserve wereassigned to it. [7]

It appears that General MacArthur about the middle of August had madeup his mind on the person he would select to command the invasion force.One day as he was talking with General Almond about the forthcoming landing,the latter suggested that it was time to appoint a commander for it. MacArthurturned to him and replied, "It is you." MacArthur told Almondthat he was also to retain his position as Chief of Staff, Far East Command.His view was that Almond would command X Corps for the Inch'on invasionand the capture of Seoul, that the war would end soon thereafter, and Almondwould then return to his old position in Tokyo. In effect, the Far EastCommand would lend Almond and most of the key staff members of the corpsfor the landing operation. General Almond has stated that MacArthur's decisionto place him in command of X Corps surprised him, as he had expected toremain in Tokyo in his capacity as Chief of Staff, FEC. General MacArthurofficially assigned General Almond to command X Corps on 26 August. [8]

General Almond, fifty-eight years old when he assumed command of X Corps,was a graduate of Virginia Military Institute. In World War I he had commandeda machine gun battalion and had been wounded and decorated for bravery.In World War II he had commanded the 92d Infantry Division in Italy. Almondwent to the Far East Command in June 1946, and served as deputy chief ofstaff to MacArthur from November 1946 to February 1949. On 18 February1949 he became Chief of Staff, Far East Command, and, on 24 July 1950,Chief of Staff, United Nations Command, as well.

General Almond was a man both feared and obeyed throughout the Far EastCommand. Possessed of a driving energy and a consuming impatience withincompetence, he expected from others the same degree of devotion to dutyand hard work that he exacted from himself. No one who ever saw him wouldbe likely to forget the lightning that flashed from his blue eyes. To hiscommander, General MacArthur, he was wholly loyal. He never hesitated beforedifficulties. Topped by iron-gray hair, Almond's alert, mobile face withits ruddy complexion made him an arresting figure despite his medium statureand the slight stoop of his shoulders.

The corps' chief of staff was Maj. Gen. Clark L. Ruffner, who had arrivedfrom the United States on 6 August and had started working with the planning group two days later. He was an energeticand diplomatic officer with long experience and a distinguished recordin staff work. During World War II he had been Chief of Staff, U.S. ArmyForces, Pacific Ocean Areas, in Hawaii. The X Corps staff was an able one,many of its members hand-picked from among the Far East Command staff.

The major ground units of X Corps were the 1st Marine Division and the7th Infantry Division. In the summer of 1950 it was no easy matter forthe United States to assemble in the Far East a Marine division at fullstrength. On 25 July, Maj. Gen. Oliver P. Smith assumed command and onthat day the Commandant of the Marine Corps issued an order to him to bringthe division to war strength, less one regiment, and to sail for the FarEast between 10 and 15 August. This meant the activation of another regiment,the 1st Marines, and the assembly, organization, and equipment of approximately15,000 officers and enlisted men within the next two weeks. On 10 August,the Joint Chiefs of Staff decided to add the third regiment to the division,and the 7th Marines was activated. It was scheduled to sail for the FarEast by 1 September. The difficulty of obtaining troops to fill the divisionwas so great that a battalion of marines on duty with the Sixth Fleet inthe Mediterranean was ordered to join the division in the Far East. [9]

General Smith and most of the staff officers of the 1st Marine Divisionarrived in Japan from the United States on 22 August. The division troops,the 1st Marines, and the staff of the 7th Marines arrived in Japan between28 August and 6 September. A battalion of marines in two vessels, the Bexarand the Montague, departed Suda Bay, Crete, in the Mediterraneanon 16 August, and sailing by way of Suez arrived at Pusan on 9 Septemberto join the 7th Marines as its 3d Battalion. The remainder of the 7th Marinesarrived at Kobe on 17 September. The 5th Marines, in Korea, received awarning order on 30 August to prepare for movement to Pusan to join thedivision. [10]

Bringing the 7th Infantry Division up to war strength posed an evenmore difficult problem. During July, FEC had taken 140 officers and 1,500noncommissioned officers and enlisted men from the division to augmentthe strength of the 24th and 25th Infantry and the 1st Cavalry Divisionsas they in turn had mounted out for Korea. At the end of July the divisionwas at less than half-strength, but in noncommissioned officer weaponsleaders and critical specialists the shortage was far greater than thatproportion. On 27 July, the 7th Infantry Division was 9,117 men understrength-290officers, 126 warrant officers, and 8,701 enlisted men. The day before,FEC had relieved it of all occupation duties and ordered it to preparefor movement to Korea. [11]

From 23 August to 3 September the Far East Command allotted to the 7thDivision the entire infantry replacement stream reaching FEC, and from23 August through 8 September the entire artillery replacement stream.By 4 September the division had received 390 officers and 5,400 enlistedreplacements. General MacArthur obtained service units for the X Corpsin the same way-by diverting them from scheduled assignments for EighthArmy. The Far East Command justified this on the ground that, while EighthArmy needed them badly, X Corps' need was imperative. [12]

In response to General MacArthur's instructions to General Walker on11 and 13 August to send South Koreans to augment the 7th Infantry Division,8,637 of them arrived in Japan before the division embarked for Inch'on.Their clothing on arrival ranged from business suits to shirts and shorts,or shorts only. The majority wore sandals or cloth shoes. They were civilians-stunned,confused, and exhausted. Only a few could speak English. Approximately100 of the South Korean recruits were assigned to each rifle company andartillery battery; the buddy system was used for training and control.[13]

The quality of the artillery and infantry crew-served weapons troopsreceived from the United States and assigned to the 7th Division duringAugust and early September was high. The superior training provided bythe old infantry and artillery noncommissioned officers who arrived fromthe Fort Benning Infantry and the Fort Sill Artillery Schools brought the7th Division to a better condition as the invasion date approached thancould have been reasonably expected a month earlier. The 7th Division strengthon embarkation, including the attached South Koreans, was 24,845. [14]

All through July and August 1950 the Joint Chiefs of Staff gave impliedor expressed approval of MacArthur's proposal for an amphibious landingbehind the enemy's battle lines. But while it was known that MacArthurfavored Inch'on as the landing site, the Joint Chiefs had never committedthemselves to it. From the beginning, there had been some opposition toand many reservations about the Inch'on proposal on the part of GeneralCollins, U.S. Army Chief of Staff; the Navy; and the Marine Corps. TheFEC senior planning and staff officers-such as Generals Almond and Hickey,Chief of Staff and Deputy Chief of Staff; General Wright, the G-3 and headof JSPOG; and Brig. Gen. George L. Eberle, the G-4-supported the plan.[15]

The Navy's opposition to the Inch'on site centered largely on the difficulttidal conditions there, and since this opposition continued, the Joint Chiefsof Staff decided to send two of its members to Tokyo to discuss the matterwith MacArthur and his staff. A decision had to be reached. On 20 JulyGeneral Collins and Admiral Forrest P. Sherman, Chief of Naval Operations,left Washington for their conference with MacArthur. Upon arrival in Japan,Collins and Sherman engaged in private conversations with MacArthur andkey members of his staff, including senior naval officers in the Far East.Then, on the afternoon of 23 July, a full briefing on the subject was scheduledin General MacArthur's conference room in the Dai Ichi Building. [16]

The conference began at 1730 in the afternoon. Among those present inaddition to General MacArthur were General Collins, Admiral Sherman, ViceAdmirals Joy and Struble, Generals Almond, Hickey, and Wright, some membersof the latter's JSPOG group, and Rear Adm. James H. Doyle and some membersof his staff who were to present the naval problems involved in a landingat Inch'on.

After a short introduction by General MacArthur, General Wright briefedthe group on the basic plan. Admiral Doyle then presented the naval considerations.His general tone was pessimistic, and he concluded with the remark, "Theoperation is not impossible, but I do not recommend it." The navalpart of the briefings lasted more than an hour.

During the naval presentation MacArthur, who had heard the main argumentsmany times before, sat quietly smoking his pipe, asking only an occasionalquestion. When the presentation ended, MacArthur began to speak. He talkedas though delivering a soliloquy for forty-five minutes, dwelling in aconversational tone on the reasons why the landing should be made at Inch'on.He said that the enemy had neglected his rear and was dangling on a thinlogistical rope that could be quickly cut in the Seoul area, that the enemyhad committed practically all his forces against Eighth Army in the southand had no trained reserves and little power of recuperation. MacArthurstressed the strategical, political, and psychological reasons for thelanding at Inch'on and the quick capture of Seoul, the capital of SouthKorea. He said it would hold the imagination of Asia and win support forthe United Nations. Inch'on, he said, pointing to the big map behind him,would be the anvil on which the hammer of Walker's Eighth Army from thesouth would crush the North Koreans.

General MacArthur then turned to a consideration of a landing at Kunsan,100 air miles below Inch'on, which General Collins and Admiral Shermanhad favored. MacArthur said the idea was good but the location wrong. Hedid not think a landing there would result in severing the North Koreansupply lines and destroying the North Korean Army. He returned to his emphasison Inch on, saying that the amphibious landing was tactically the mostpowerful military device available to the United Nations Command and thatto employ it properly meant to strike deep and hard into enemy-held territory.He dwelt on the bitter Korean winter campaign that would become necessaryif Inch'on was not undertaken. He said the North Koreans considered a landing at Inch'on impossible because of the verygreat difficulties involved and, because of this, the landing force wouldachieve surprise. He touched on his operations in the Pacific in WorldWar II and eulogized the Navy for its part in them. He concluded his longtalk by declaring unequivocally for Inch'on and saying, "The Navyhas never turned me down yet, and I know it will not now."

MacArthur seems to have convinced most of the doubters present. AdmiralSherman was won over to MacArthur's position. General Collins, however,seemed still to have reservations on Inch'on. He subsequently asked GeneralWright if the Far East Command had firm plans for a Kunsan landing whichcould be used as an alternate plan if the Inch'on operation either wasnot carried out or failed. Wright assured him that there were such plansand, moreover, that it was planned to stage a feint at Kunsan. [17]

Among the alternate proposals to Inch'on, in addition to the Kunsanplan favored by the Navy, was one for a landing in the Posung-myon areathirty miles south of Inch'on and opposite Osan. On the 23d, Admiral Doylehad proposed a landing there with the purpose of striking inland to Osanand there severing the communications south of Seoul. On the 24th, Lt.Gen. Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr. (USMC), called on General MacArthur and askedhim to change the landing site to this area-all to no avail. MacArthurremained resolute on Inch'on.

Upon their return to Washington, Collins and Sherman went over the wholematter of the Inch'on landing with the other members of the Joint Chiefsof Staff. On 28 August the Joint Chiefs sent a message to MacArthur whichseemingly concurred in the Inch'on plans yet attached conditions. Theirmessage said in part: "We concur in making preparations for and executinga turning movement by amphibious forces on the west coast of Korea, eitherat Inch'on in the event the enemy defenses in the vicinity of Inch'on proveineffective, or at a favorable beach south of Inch'on if one can be located.We further concur in preparations, if desired by CINCFE, for an envelopmentby amphibious forces in the vicinity of Kunsan. We understand that alternativeplans are being prepared in order to best exploit the situation as it develops.[18]

MacArthur pressed ahead unswervingly toward the Inch'on landing. On30 August he issued his United Nations Command operation order for it.Meanwhile, the Joint Chiefs in Washington expected to receive from MacArthurfurther details of the pending operation and failing to receive them, senta message to him on 5 September requesting this information. MacArthurreplied the next day that his plans remained unchanged. On 7 September,the Joint Chiefs sent another message to MacArthur requesting a reconsiderationof the whole question and an estimate of the chances for favorable outcome.The energy and strength displayed by the North Koreans in their early Septembermassive offensive had evidently raised doubts in the minds of the JointChiefs that General Walker's Eighth Army could go over successfully tothe attack or that X Corps could quickly overcome the Seoul defenses. Inthe meantime, General MacArthur on 6 September in a letter to all his majorcommanders confirmed previous verbal orders and announced 15 Septemberas D-day for the Inch'on landing. [19]

In response to the Joint Chiefs' request for a reconsideration and anestimate of the chances for a favorable landing at Inch'on, General MacArthuron 8 September sent to Washington a final eloquent message on the subject.His message said in part:

There is no question in my mind as to the feasibility of the operationand I regard its chance of success as excellent. I go further and believethat it represents the only hope of wresting the initiative from the enemyand thereby presenting an opportunity for a decisive blow. To do otherwiseis to commit us to a war of indefinite duration, of gradual attrition,and of doubtful results.... There is no slightest possibility . . . ofour force being ejected from the Pusan beachhead. The envelopment fromthe north will instantly relieve the pressure on the south perimeter and,indeed, is the only way that this can be accomplished.... The success ofthe enveloping movement from the north does not depend upon the rapid junctureof the X Corps and the Eighth Army. The seizure of the heart of the enemydistributing system in the Seoul area will completely dislocate the logisticalsupply of his forces now operating in South Korea and therefore will ultimatelyresult in their disintegration. This, indeed, is the primary purpose ofthe movement. Caught between our northern and southern forces, both ofwhich are completely self-sustaining because of our absolute air and navalsupremacy, the enemy cannot fail to be ultimately shattered through disruptionof his logistical support and our combined combat activities.... For thereasons stated, there are no material changes under contemplation in theoperation as planned and reported to you. The embarkation of the troopsand the preliminary air and naval preparations are proceeding accordingto schedule.

The next day the Joint Chiefs, referring to this message, replied terselyto MacArthur, "We approve your plan and President has been so informed."[20] It appears that in Secretary of Defense Johnson, MacArthur had inWashington a powerful ally during the Inch'on landing controversy, forJohnson supported the Far East commander. [21] Thus on 8 September Washingtontime and 9 September Tokyo time the debate on the projected Inch'on landingended.

A co-ordinate part of MacArthur's Inch'on plan was an attack by theEighth Army north from its Pusan Perimeter beachhead simultaneously with the X Corps landing. This actionwas intended to tie down all enemy forces committed against Eighth Armyand prevent withdrawal from the south of major reinforcements for the NorthKorean units opposing X Corps in its landing area. The plan called forthe Eighth Army to break out of the Perimeter, drive northward, and joinforces with X Corps.

On 30 August, General Smith had sent a dispatch to X Corps requestingthat the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade in Korea be released from EighthArmy on 1 September to prepare for mounting out for Inch'on. MacArthurordered that the Marine brigade be available on 4 September for that purpose.But no sooner was this order issued than it was rescinded on 1 Septemberbecause of the crisis that faced Eighth Army after the great North Koreanattack had rolled up the southern front during the night. [22]

Eighth Army's use of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade in the battlenear Yongsan threatened to disrupt the Inch'on landing according to Marineand Navy opinion. A tug of war now ensued between General Smith, supportedby the U.S. Naval Forces, Far East, on the one hand and General Walkeron the other for control of the 5th Marines. The Marine commander insistedhe must have the 5th Marines if he were to make the Inch'on landing. GeneralWalker in a telephone conversation with General Almond said in effect,"If I lose the 5th Marine Regiment I will not be responsible for thesafety of the front." Almond sided with Walker despite the fact thathe was to be commander of the Inch'on landing force, taking the view thatthe X Corps could succeed in its plan without the regiment. He suggestedthat the 32d Infantry Regiment of the 7th Division be attached to the 1stMarine Division as its second assault regiment. General Smith and NAVFEremained adamant. The issue came to a head on 3 September when AdmiralsJoy, Struble, and Doyle accompanied General Smith to the Dai Ichi Buildingfor a showdown conference with Generals Almond, Ruffner, and Wright.

When it became clear that the group could not reach an agreement, GeneralAlmond went into General MacArthur's private office and told MacArthurthat things had reached an impasse-that Smith and the Navy would not goin at Inch'on without the 5th Marines. Hearing this, MacArthur told Almond,"Tell Walker he will have to give up the 5th Marine Regiment."Almond returned to the waiting group and told them of MacArthur's decision.[23]

The next day, 4 September, General MacArthur sent General Wright toTaegu to tell General Walker that the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade wouldhave to be released not later than the night of 5-6 September and movedat once to Pusan. At Taegu Wright informed Walker of MacArthur's instructionsand told him that the Far East Command was loading the 17th Regiment ofthe 7th Infantry Division for movement to Pusan, where it would be heldin floating reserve and be available for use by Eighth Army if necessary. (It sailed from Yokohama for Koreaon 6 September.) He also said that MacArthur intended to divert to Pusanfor assignment to Eighth Army the first regiment (65th Infantry) of the3d Infantry Division arriving in the Far East, the expected date of arrivalbeing 18-20 September. General Walker, in discussing his part in the projectedcombined operation set for 15 September, requested that the Eighth Armyattack be deferred to D plus 1, 16 September. Wright agreed with this timingand said he would recommend it to MacArthur, who subsequently approvedit. [24]

In making ready its part of the operation, the Commander, NAVFE outlinedthe tasks the Navy would have to perform. These included the following:maintain a naval blockade of the west coast of Korea south of latitude39° 35' north; conduct pre-D-day naval operations as the situationmight require; on D-day seize by amphibious assault, occupy, and defenda beachhead in the Inch'on area; transport, land, and support follow-upand strategic reserve troops, if directed, to the Inch'on area; and providecover and support as required. Joint Task Force Seven was formed to accomplishthese objectives with Admiral Struble, Commander, Seventh Fleet, as thetask force commander. On 25 August, Admiral Struble left his flagship,USS Rochester, at Sasebo and proceeded by air to Tokyo to directfinal planning. [25]

On 3 September, Admiral Struble issued JTF 7 Operational Plan 9-50.Marine aircraft from two escort carriers, naval aircraft from the U.S.carrier Boxer, and British aircraft from a light British carrierwould provide as much support aircraft as could be concentrated in andover the landing area, and would be controlled from the amphibious forceflagship (AGC) Mt. McKinley. An arc extending inland thirtymiles from the landing site described the task force objective area. [26]In order to carry out its various missions, Joint Task Force Seven organizedits subordinate parts as follows:

TF 90: Attack Force, Rear Adm. James H. Doyle, USN

TF 92: X Corps, Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond, USA

TF 99: Patrol & Reconnaissance Force, Rear Adm. G. R. Henderson,USN

TF 91: Blockade & Covering Force, Rear Adm. W. G. Andrews, R.N.

TF 77: Fast Carrier Force, Rear Adm. E. C. Ewen, USN

TF 79: Logistic Support Force, Capt. B. L. Austin, USN

TF 70.1: Flagship Group, Capt. E. L. Woodyard, USN

For the naval phases, the command post of Admiral Struble was on theRochester; that of Rear Admiral Doyle, second in command, was onthe Mt. McKinley.

More than 230 ships were assigned to the operation. Surface vesselsof JTF 7 were not to operate within twelve miles of Soviet or Chinese territorynor aircraft within twenty miles of such territory. [27]

MacArthur had selected Inch'on as the landing site for one paramountreason: it was the port for the capital city of Seoul, eighteen miles inland,and was the closest possible landing area to that city and the hub of communicationscentering there.

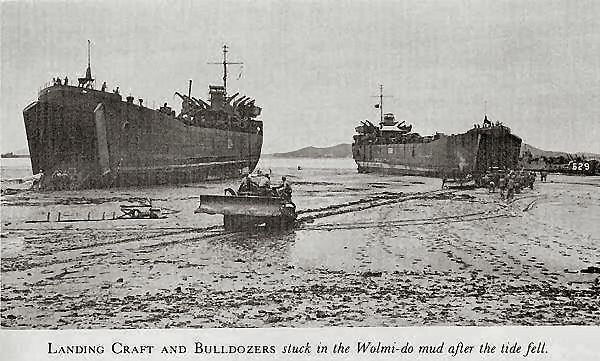

Inch'on is situated on the estuary of the Yom-ha River and possessesa protected, ice-free port with a tidal basin. The shore line there isa low-lying, partially submerged coastal plain subject to very high tides.There are no beaches in the landing area-only wide mud flats at low tideand stone walls at high tide. Because of the mud flats, the landing forcewould have to use the harbor and wharfage facilities in the port area.The main approach by sea is from the south through two channels 50 mileslong and only 6 to 10 fathoms deep (36-60 feet). Flying Fish Channel isthe channel ordinarily used by large ships. It is narrow and twisting.

The Inch'on harbor divides into an outer and an inner one, the latterseparated from the former by a long breakwater and the islands of Wolmiand Sowolmi which join by a causeway. The greater part of the inner harborbecomes a mud flat at low tide leaving only a narrow dredged channel ofabout ~13 feet in depth. The only dock facilities for deep draft vesselswere in the tidal basin, which was 1,700 feet long, 750 feet wide, andhad an average depth of 40 feet, but at mean low tide held only feet ofwater. [28]

Inch'on promised to be a unique amphibious operation-certainly one verydifficult to conduct because of natural conditions. Tides in the restrictedwaters of the channel and the harbor have a maximum range of more than31 feet. A few instances of an extreme 33-foot tide have been reported.Some of the World War II landing craft that were to be used in making thelanding required 23 feet of tide to clear the mud flats, and the LST's(Landing Ship, Tank) required 29 feet of tide-a favorable condition thatprevailed only once a month over a period of three or four days. The narrow,shallow channel necessitated a daylight approach for the larger ships.Accordingly, it was necessary to schedule the main landings for the lateafternoon high tide. A night approach, however, by a battalion-sized attackgroup was to be made for the purpose of seizing Wolmi-do during the earlymorning high tide, a necessary preliminary, the planners thought, to themain landing at Inch'on itself. [29]

Low seas at Inch'on are most frequent from May through August, highseas from October through March. Although September is a period of transition,it was considered suitable for landing operations. MacArthur and his plannershad selected 15 September for D-day because there would then be a hightide giving maximum water depth over the Inch'on mud flats. Tidal rangefor 15 September reached 31.2 feet at high and minus .5 feet at low water. Only on thisday did the tide reach this extreme range. No other date after this wouldpermit landing until 27 September when a high tide would reach 27 feet.On 11-13 October there would be a tide of 30 feet. Morning high tide on15 September came at 0659, forty-five minutes after sunrise; evening hightide came at 1919, twenty-seven minutes after sunset. The Navy set 23 feetof tide as the critical point needed for landing craft to clear the mudflat and reach the landing sites. [30]

Another consideration was the sea walls that fronted the Inch'on landingsites. Built to turn back unusually high tides, they were 16 feet in heightabove the mud flats. They presented a scaling problem except at extremehigh tide. Since the landing would be made somewhat short of extreme hightide in order to use the last hour or two of daylight, ladders would beneeded. Some aluminum scaling ladders were made in Kobe and there wereothers of wood. Grappling hooks, lines, and cargo nets were readied foruse in holding the boats against the sea wall.

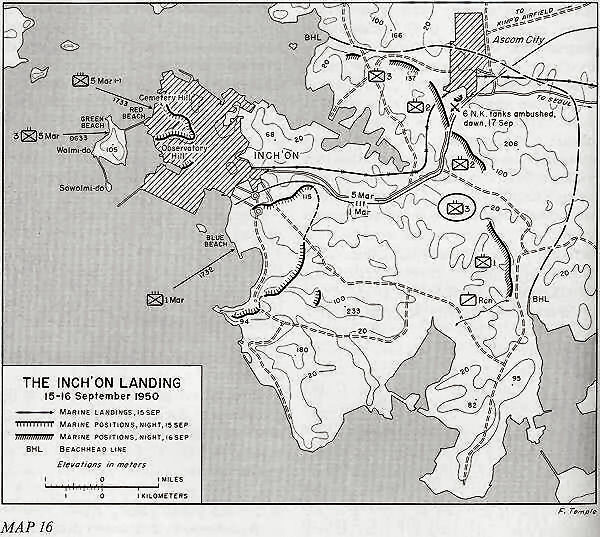

The initial objective of the landing force was to gain a beachhead atInch'on, a city of 250,000 population. The 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, wasto land on Wolmi-do on the early morning high tide at 0630, 15 September(D-day, L-hour). With Wolmi-do in friendly hands, the main landing wouldbe made that afternoon at the next high tide, about 1730 (D-day, H-hour),by the 1st and 5th Marines.

Three landing beaches were selected-Green Beach on Wolmi-do for thepreliminary early morning battalion landing, and Red Beach in the sea walldock area of Inch'on and Blue Beach in the mud flat semi-open area at thesouth edge of the city for the two-regimental-size force that would makethe main landing in the evening. Later, 7th Infantry Division troops wouldland at Inch'on over what was called Yellow Beach.

The 5th Marines, less the 3d Battalion, was to land over Red Beach inthe heart of Inch'on, north of the causeway which joined Wolmi-do withInch'on, and drive rapidly inland 1,000 yards to seize Observatory Hill.On the left of the landing area was Cemetery Hill, 130 feet high, on whichthree dual-purpose guns reportedly were located. On the right, a groupof buildings dominated the landing area. The 5th Marines considered Cemeteryand Observatory Hills as the important ground to be secured in its zone.

Simultaneously with the 5th Marines' landing, the 1st Marines was toland over Blue Beach at the base of the Inch'on Peninsula just south ofthe city. This landing area had such extensive mud flats that heavy equipmentcould not be brought ashore over it. It lay just below the tidal basinof the inner harbor and an adjacent wide expanse of salt evaporators. Itsprincipal advantage derived from the fact that the railroad and main highwayto Seoul from Inch'on lay only a little more than a mile inland from it.A successful landing there could quickly cut these avenues of escape oraccess at the rear of Inch'on. [31]

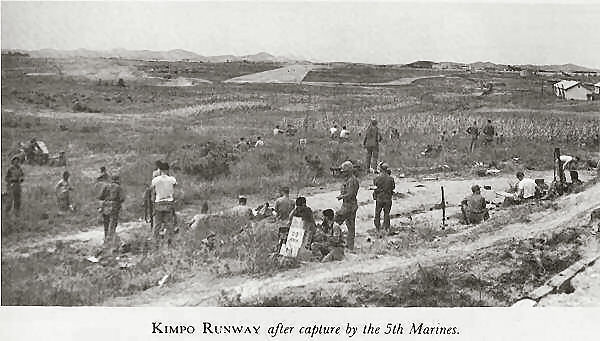

An early objective of the 1st Marine Division after securing the beachheadwas Kimpo Airfield, sixteen road miles northeast of Inch'on. Then wouldfollow the crossing of the Han River and the drive on Seoul.

As diversions, the battleship Missouri was to shell east coastareas on the opposite side of the Korean peninsula, including the railcenter and port of Samch'ok, and a small force was to make a feint at Kunsanon the west coast, 100 air miles south of Inch'on.

General MacArthur's view at the end of August that the North Koreanshad concentrated nearly all their combat resources against Eighth Armyin the Pusan Perimeter coincided with the official G-2 estimate. On 28August the X Corps G-2 Section estimated the enemy strength in Seoul asapproximately 5,000 troops, in Inch'on as 1,000, and at Kimpo Airfieldas 500, for a total of 6,500 soldiers in the Inch'on-Seoul area. On 4 Septemberthe estimate remained about the same except that the enemy force in theInch'on landing area was placed at 1,800-2,500 troops because of an anticipatedbuild-up there. This estimate remained relatively unchanged four days later,and thereafter held constant until the landing. [32]

American intelligence considered the enemy's ability to reinforce quicklythe Inch'on-Seoul area as inconsequential. It held the view that only smallrear area garrisons, line of communications units, and newly formed, poorlytrained groups were scattered throughout Korea back of the combat zonearound the Pusan Perimeter. Aerial reconnaissance reported heavy movementof enemy southbound traffic from the Manchurian border, but it was notclear whether this was of supplies or troops, or both. Although reportsshowed that the Chinese Communist Forces had increased in strength alongthe Manchurian border, there was no confirmation of rumors that some ofthem had moved into North Korea. [33]

The Far East Command considered the possibility that the enemy mightreinforce the Inch'on-Seoul area from forces committed against Eighth Armyin the south. If this were attempted, it appeared that the North Korean3d, 13th, and 10th Divisions, deployed on eitherside of the main Seoul-Taejon-Taegu highway, could most rapidly reach theInch'on area.

North Korean air and naval elements were considered incapable of interferingwith the landing. On 28 August the Far East Command estimated there wereonly nineteen obsolescent Soviet-manufactured aircraft available to theNorth Korean Air Force. The U.N. air elements, nevertheless, had ordersto render unusable any known or suspected enemy air facilities, and particularlyto give attention to new construction at Kimpo, Suwon, and Taejon. NorthKorean naval elements were almost nonexistent at this time. Five divisionsof small patrol-type vessels comprised the North Korean Navy; one was onthe west coast at Chinnamp'o, the others at Wonsan on the east coast. Atboth places they were bottled up and rendered impotent. On the morning of 7 Septembera ROK patrol vessel (PC boat) north of Inch'on discovered and sank a smallcraft engaged in mine laying; thus it appeared that some mines were tobe expected. [34]

As a final means of checking on conditions in Inch'on harbor, the Navyon 31 August sent Lt. Eugene F. Clark to Yonghung-do, an island at themouth of the ship channel ten sea miles from Inch'on. There, Clark usedfriendly natives to gather the information needed. He sent them on severaltrips to Inch'on to measure water depths, check on the mud flats, and toobserve enemy strength and fortifications. He transmitted their reportsby radio to friendly vessels in Korean waters. Clark was still in the outerharbor when the invasion fleet entered it. [35]

At the end of August the ports of Kobe, Sasebo, and Yokohama in Japanand Pusan in Korea had become centers of intense activity as preparationsfor mounting the invasion force entered the final stage. The 1st MarineDivision, less the 5th Marines, was to outload at Kobe, the 5th Marinesat Pusan, and the 7th Infantry Division at Yokohama. Most of the escortingvessels, the Gunfire Support Group, and the command ships assembled atSasebo.

The ships to carry the troops, equipment, and supplies began arrivingat the predesignated loading points during the last days of August. Inorder to reach Inch'on by morning of 15 September, the LST's had to leaveKobe on 1o September and the transports (AP's) and cargo ships (AK's) on12 September. Only the assault elements were combat-loaded. Japanese crewsmanned thirty-seven of the forty-seven LST's in the Marine convoy. [36]

The loading of the 1st Marine Division at Kobe was in full swing on2 September when word came that the next morning a typhoon would strikethe port, where more than fifty vessels were assembled. All unloading andloading stopped for thirty-six hours. At 0600 on 3 September, Typhoon Janescreeched in from the east. Wind velocity reached 110 miles an hour atnoon. Waves forty feet high crashed against the waterfront and breakersrolled two feet high across the piers where loose cargo lay. Seven Americanships broke their lines and one of the giant 200-ton cranes broke loose.Steel lines two and a half inches thick snapped. Only by exhausting anddangerous work did port troops and the marines fight off disaster. By 1530in the afternoon the typhoon began to blow out to sea. An hour later relativecalm descended on the port and the cleanup work began. A few vessels hadto go into drydock for repairs, some vehicles were flooded out, and a largequantity of clothing had to be cleaned, dried, and repackaged. [37]

Despite the delay and damage caused by Jane, the port of Kobeand the 1st Marine Division met the deadline of outloading by 11 September.On the 10th and the 11th, sixty-six cargo vessels cleared Kobe for Inch'on.They sailed just ahead of another approaching typhoon. This second typhoonhad been under observation by long-range reconnaissance planes since 7September. Named Kezia, it was plotted moving from the southwestat a speed that would put it over the Korean Straits on 12-13 September.

On the 11th, the 1st Marine Division sailed from Kobe and the 7th InfantryDivision from Yokohama. The next day the 5th Marines departed Pusan torendezvous at sea. The flagship Rochester with Admiral Struble aboardgot under way from Sasebo for Inch'on at 1530, 12 September. That afternoona party of dignitaries, including Generals MacArthur, Almond, Wright, Maj.Gen. Alonzo P. Fox, Maj. Gen. Courtney Whitney, and General Shepherd ofthe Marine Corps, flew from Tokyo to Itazuke Air Base and proceeded fromthere by automobile to Sasebo, arriving at 2120. Originally, the MacArthurparty had planned to fly from Tokyo on the 13th and embark on the Mt.McKinley at Kokura that evening. But Typhoon Kezia's suddenchange of direction caused the revision of plans to assure that the partywould be embarked in time. The Mt. McKinley, sailing fromKobe with Admiral Doyle and General Smith aboard, had not yet arrived atSasebo when MacArthur's party drove up. It finally pulled in at midnight,and departed for the invasion area half an hour later after taking MacArthur'sparty aboard. [38]

Part of the invasion fleet encountered very rough seas off the southerntip of Kyushu early on 13 September. Winds reached sixty miles an hourand green water broke over ships' bows. In some cases, equipment shiftedin the holds, and in other instances deck-loaded equipment was damaged.During the day the course of Kezia shifted to the northeast andby afternoon the seas traversed by the invasion fleet began to calm. Theaircraft carrier Boxer, steaming at forced speed from the Californiacoast with 110 planes aboard, fought the typhoon all night in approachingJapan. At dusk on the 14th, it quickly departed Sasebo and at full speedcut through the seas for Inch'on. [39]

Air attacks intended to isolate the invasion area began on 4 Septemberand continued until the landing. On the 10th, Marine air elements struckWolmi-do in a series of napalm attacks. Altogether, sixty-five sortieshit Inch'on during the day. [40]

The main task of neutralizing enemy batteries on Wolmi-do guarding theInch'on inner harbor was the mission of Rear Adm. J. M. Higgins' GunfireSupport Group. This group, composed of 2 United States heavy cruisers, 2 British light cruisers, and 6 U.S. destroyers,entered the approaches to Inch'on harbor at 1010, 13 September. Just beforenoon the group in Flying Fish Channel sighted an enemy mine field, exposedat low water. It destroyed some of the mines with automatic fire. At 1220,the 4 cruisers anchored from seven to ten miles offshore, while 5 destroyers-theMansfield, DeHaven, Swenson, Collett, and Gurke-proceededon to anchorages close to Wolmi-do under cover of air strikes by planesfrom Fast Carrier Task Force 77. The destroyers began the bombardment ofWolmi-do at 1230. [41]

Five enemy heavily revetted 75-mm. guns returned the fire. In the intenseship-shore duel, the Collett received nine hits and sustained considerabledamage. Enemy shells hit the Gurke three times, but caused no seriousdamage. The Swenson took a near miss which caused two casualties:one was Lt. (jg.) David H. Swenson, the only American killed during thebombardment. The destroyers withdrew at 1347.

At 1352 the cruisers, anchored out of range of the Wolmi-do batteries,began an hour and a half bombardment. Planes of Task Force 77 then camein for a heavy strike against the island. After the air strike terminated,the cruisers resumed their bombardment at 1610 for another half hour. Thenat 1645 the Gunfire Support Group got under way and withdrew back downthe channel. [42]

The next day, D minus 1, the Gunfire Support Group returned. Just before1100, planes of Task Force 77 again delivered heavy strikes against theisland. The heavy cruisers began their second bombardment at 1116, thistime also taking under fire targets within Inch'on proper. The destroyerswaited about an hour and then moved to their anchorages off Wolmi-do. Thecruisers ceased firing while another air strike came in on the island.After it ended, the five destroyers began their bombardment at 1255 andin an hour and fifteen minutes fired 1,732 5-inch shells into Wolmi-doand Inch'on. When they left there was no return fire-the Wolmi-do batterieswere silent. [43]

The X Corps expeditionary troops arriving off Inch'on on 15 Septembernumbered nearly 70,000 men. [44] At 0200 the Advance Attack Group, including the Gunfire Support Group, the rocketships (LSMR's) and the Battalion Landing Team, began the approach to Inch'on.A special radar-equipped task force, consisting of three high speed transports(APD's) and one Landing Ship Dock (LSD), carried the Battalion LandingTeam-Lt. Col. Robert D. Taplett's 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, and a platoonof nine M26 Pershing tanks from A Company, 1st Tank Battalion-toward thetransport area off Wolmi-Do. Dawn of invasion day came with a high overcastsky and portent of rain. [45]

Wolmi-do, or Moon Tip Island, as it might be translated, is a circularhill (Hill 105) about 1,000 yards across and rising 335 feet above thewater. A rocky hill, it was known to be honeycombed with caves, trenches,gun positions, and dugouts. (Map 16) The first action came at 0500. Eight Marine Corsairs left their escort carrier for a strike on Wolmi-do.The first two planes caught an armored car crossing the causeway from Inch'onand destroyed it. There was no other sign of life visible on the islandas the flight bombed the ridge line. At 0530 the Special Task Force wasin its designated position ready to land the assault troops. Twenty minuteslater, Taplett's 3d Battalion began loading into 17 landing craft (LCVP's);the 9 tanks loaded into 3 landing ships (LSV's). L-hour was fifty minutesaway.

Air strikes and naval gunfire raked Wolmi-do and, after this, threerocket ships moved in close and put down an intense rocket barrage. Thelanding craft straightened out into lines from their circles and movedtoward the line of departure. Just as a voice announced over the ship'sloud speaker, "Landing force crossing line of departure," MacArthurcame on the bridge of the Mt. McKinley. It was 0625. Thefirst major amphibious assault by American troops against an enemy sinceEaster Sunday, 1 April 1945, at Okinawa was under way. About one mile ofwater lay between the line of departure and the Wolmi-do beach. [46]

The 3d Battalion moved toward Wolmi-do with G and H Companies in assaultand I Company in reserve. Even after the American rocket barrage liftedthere was still no enemy fire. The first wave of troops reached the bathingbeach on the northern arm of the island unopposed at 0633.

The first troops ashore moved rapidly inland against almost no resistance.Within a few minutes the second wave landed. Then came the LSV's carrying the tanks, three of which carried dozer blades for breaking up barbedwire, filling trenches, and sealing caves; three other tanks mounted flamethrowers. One group of marines raised the American flag on the high groundof Wolmi-do half an hour after landing. Another force crossed the islandand sealed off the causeway leading to Inch'on. The reduction of the islandcontinued systematically and it was secured at 0750. [47]

A little later in the morning, Colonel Taplett sent a squad of marinesand three tanks over the causeway to Sowolmi-do where they destroyed anestimated platoon of enemy troops; some surrendered, others swam into thesea, and still others were killed. Taplett's battalion assumed defensivepositions and prepared to cover the main Inch'on landing later in the day.

In the capture of Wolmi-do and Sowolmi-do the Battalion Landing Teamkilled 108 enemy soldiers and captured 136. About 100 more in several cavesrefused to surrender and were sealed by tank dozers into their caves. Marinecasualties were light-seventeen wounded. [48]

The preinvasion intelligence on Wolmi-do proved to be essentially correct.Prisoners indicated that about 400 North Korean soldiers, elements of the3d Battalion, 226th Independent Marine Regiment,and some artillery troops of the 918th Artillery Regimenthad defended Wolmi-do.

After the easy capture of Wolmi-do came the anxious period when thetide began to fall, causing further activity to cease until late in theafternoon. The enemy by now was fully alerted. Marine and naval air rangedup and down the roads and over the countryside isolating the port to adepth of twenty-five miles, despite a rain which began to fall in the lateafternoon. Naval gunfire covered the closer approaches to Inch'on.

Assault troops of the 5th and 1st Marines began going over the sidesof their transports and into the landing craft at 153O. After a naval bombardment,rocket ships moved in close to Red and Blue Beaches and fired 2,000 rocketson the landing areas. Landing craft crossed lines of departure at 1645,and forty-five minutes later neared the beaches. The first wave of the5th Marines breasted the sea wall on Red Beach at 1733. Most of the A Companymen in the fourteen boats of the first three waves climbed over the seawall with scaling ladders; a few boats put their troops ashore throughholes in the wall made by the naval bombardment. [49]

On the left flank of the landing area, the 3d Platoon of A Company encounteredenemy troops in trenches and a bunker just beyond the sea wall. There inan intense fight the marines lost eight men killed and twenty-eight wounded.Twenty-two minutes after landing, the company fired a flare signaling thatit held Cemetery Hill. On top of Cemetery Hill, North Koreans threw downtheir arms and surrendered to the 2d Platoon. Other elements of the battalion by midnight had fought their wayagainst sporadic resistance to the top of Observatory Hill.

The 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, landing on the right side of Red Beach,encountered only spotty resistance and at a cost of only a few casualtiesgained its objective.

Assault elements of the 1st Marines began landing over Blue Beach at1732, one minute ahead of the 5th Marines at Red Beach. Most of the menwere forced to climb a high sea wall to gain exit from the landing area.One group went astray in the smoke and landed on the sea wall enclosingthe salt flats on the left of the beach. The principal obstacle the 1stMarines encountered was the blackness of the night. Lt. Col. Allan Sutter's2d Battalion lost one man killed and nineteen wounded in advancing to theInch'on-Seoul highway, one mile inland. The landing force had taken itsfinal D-day objectives by 0130, 16 September. [50]

Following the assault troops, eight specially loaded LST's landed atRed Beach just before high tide, and unloading of equipment to supportthe forces ashore the next day continued throughout the night. Beachingof the LST's brought tragedy. Just after 1830, after receiving some enemymortar and machine gun fire, gun crews on three of the LST's began firingwildly with 20-mm. and 40-mm. cannon, and, before they could be stopped,had killed 1 and wounded 23 men of the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines. The Marinelanding force casualties on D-day were 20 men killed, 1 missing in action,and 174 wounded. [51]

The U.N. preinvasion estimate of enemy strength at Inch'on was accurate. Prisoners disclosed that about2,000 men had comprised the Inch'on garrison. Some units of the N.K. 22dRegiment moved to Inch'on to reinforce the garrison before dawnof the 15th, but they retreated to Seoul after the main landing that evening.To the rank and file of the North Korean soldiers in Seoul the landingcame as a surprise. [52]

On the morning of 16 September the two regiments ashore establishedcontact with each other by 0730. Thereafter a solid line existed aroundInch'on and escape for any enemy still within the city became unlikely.The ROK Marines now took over mop-up work in Inch'on and went at it withsuch a will that hardly anyone in the port city, friend or foe, was safe.[53]

Early in the morning of the 16th, Marine aircraft took off from thecarriers to aid the advance. One flight of eight Corsairs left the Sicilyat 0548. Soon it sighted six enemy T34 tanks on the Seoul highway three miles east of Inch'on moving toward the latter place.Ordered to strike at once, the Corsairs hit the tanks with napalm and 500-poundbombs, damaging three of them and scattering the accompanying infantry.The enemy returned the fire, hitting one of the Corsairs. Capt. WilliamF. Simpson's plane crashed and exploded near the burning armor, killinghim. A second flight of eight Corsairs continued the attack on the tankswith napalm and bombs and, reportedly, destroyed them all. Later in themorning, however, when the advance platoon of the 1st Marines and accompanyingtanks approached the site, three of the T34's began to move, whereuponthe Pershings engaged and destroyed them. [54]

Both Marine regiments on the second day advanced rapidly against lightresistance and by evening had reached the Beachhead Line, six miles fromthe landing area. Their casualties for the day were four killed and twenty-onewounded.

Thus, within twenty-four hours of the main landing, the 1st Marine Divisionhad secured the high ground east of Inch'on, occupied an area sufficientto prevent enemy artillery fire on the landing and unloading area, andobtained a base from which to mount the attack to seize Kimpo Airfield.In the evening of 16 September General Smith established his command posteast of Inch'on and from there at 1800 notified Admiral Doyle that he wasassuming responsibility for operations ashore. [55]

During the advance thus far the boundary between the 5th and 1st Marineshad followed generally the main Inch'on-Seoul highway, which ran east-west,with the 5th Marines on the north and the 1st Marines astride and on itssouth side. Just beyond the beachhead line the boundary left the highwayand slanted northeast. This turned Colonel Murray's 5th Marines towardKimpo Airfield, seven miles away, and the Han River just beyond it. Col.Lewis B. Puller's 1st Marines, astride the Inch'on-Seoul highway, headedtoward Yongdungp'o, the large industrial suburb of Seoul on the south bankof the Han, ten air miles away.

During the night of 16-17 September, the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines,occupied a forward defensive position commanding the Seoul highway justwest of Ascom City. Behind it the 1st Battalion held a high hill. Froma forward roadblock position, members of an advanced platoon of D Company,at 0545 on the 17th, saw the dim outlines of six tanks on the road eastward.Infantry accompanied the tanks, some riding on the armor.

The enemy armored force moved past the hidden outpost of D Company.At 0600, at a range of seventy-five yards, rockets fired from a bazookaset one of the tanks on fire. Pershing tanks now opened fire on the T34's. Therecoilless rifles joined in. Within five minutes combined fire destroyedall six enemy tanks and killed 200 of an estimated 250 enemy infantry.Only one man in the 2d Battalion was wounded. [56]

Early that morning, General MacArthur, accompanied by Admiral Struble,and Generals Almond, Wright, Fox, Whitney, and others came ashore and proceededto General Smith's command post, and from there went on to the positionof the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, where they saw the numerous enemy deadand the still-burning T34 tanks. On the way they had passed the six tanksdestroyed the morning before. The sight of twelve destroyed enemy tanksseemed to them a good omen for the future. [57]

The 5th Marines advanced rapidly on the 17th and by 1800 its 2d Battalionwas at the edge of Kimpo Airfield. In the next two hours the battalionseized the southern part of the airfield. The 400-500 enemy soldiers who ineffectivelydefended it appeared surprised and had not even mined the runway. Duringthe night several small enemy counterattacks hit the perimeter positionsat the airfield between 0200 and dawn, 18 September. The marines repulsedthese company-sized counterattacks, inflicting heavy casualties on theenemy troops, who finally fled to the northwest E Company and supportingtanks played the leading role in these actions. Kimpo was secured duringthe morning of 18 September. [58]

The capture on the fourth day of the 6,000-foot-long, 150-foot-wide,hard surfaced Kimpo runway, with a weight capacity of 120,000 pounds, gavethe U.N. Command one of its major objectives. It broadened greatly thecapability of employing air power in the ensuing phases of the attack onSeoul; and, more important still, it provided the base for air operationsseeking to disrupt supply of the North Korean Army.

On the 18th, the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, sent units on to the HanRiver beyond the airfield, and the 1st Battalion captured Hill 99 northeastof it and then advanced to the river. At 1409 in the afternoon a MarineCorsair landed at Kimpo and, later in the day, advance elements of MarineAir Group 33 flew in from Japan. The next day more planes came in fromJapan, including C-54 cargo planes, and on 20 September land-based Corsairsmade the first strikes from Kimpo. [59]

Continuing its sweep along the river, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines,on the 19th swung right and captured the last high ground (Hills 118, 80,and 85) a mile west of Yongdungp'o. At the same time, the 2d Battalionseized the high ground along the Han River in its sector. At nightfall,19 September, the 5th Marines held the south bank of the Han River everywherein its zone and was preparing for a crossing the next morning. (MapVII)

Meanwhile, the 2d Engineer Special Brigade relieved the ROK Marinesof responsibility for the security of Inch'on, and the ROK's moved up onthe 18th and 19th to the Han River near Kimpo. Part of the ROK's Marinesextended the left flank of the 5th Marines, and its 2d Battalion joinedthem for the projected crossing of the Han River the next day. [60]

In this action, the 1st Marines had attacked east toward Yongdungp'oastride the Seoul highway. Its armored spearheads destroyed four enemytanks early on the morning of the 17th. Then, from positions on high ground(Hills 208, 107, 178), three miles short of Sosa, a village halfway betweenInch'on and Yongdungp'o, a regiment of the N.K. 18th Divisionchecked the advance. At nightfall the Marine regiment dug in for the nighta mile from Sosa. At Ascom City, just west of Sosa, American troops found 2,000 tons of ammunitionfor American artillery, mortars, and machine guns, captured there by theNorth Koreans in June, all still in good condition. [61]

Not all the action that day was on and over land. Just after daylight,at 0550, two enemy YAK planes made bombing runs on the Rochesterlying in Inch'on harbor. The first drop of four 100-pound bombs missedastern, except for one which ricocheted off the airplane crane withoutexploding. The second drop missed close to the port bow, causing minordamage to electrical equipment. One of the YAK's strafed H.M.S. Jamaica,which shot down the plane but suffered three casualties. [62]

Ashore, the 1st Marines resumed the attack on the morning of the 18thand passed through and around the burning town of Sosa at midmorning. Bynoon the 3d Battalion had seized Hill 123, a mile east of the town andnorth of the highway. Enemy artillery fire there caused many casualtiesin the afternoon, but neither ground nor aerial observers could locatethe enemy pieces firing from the southeast. Beyond Sosa the North Koreanshad heavily mined the highway and on 19 September the tank spearheads stoppedafter mines damaged two tanks. Engineers began the slow job of removingthe mines and, without tank support, the infantry advance slowed. But atnightfall advanced elements of the regiment had reached Kal-ch'on Creekjust west of Yongdungp'o. [63]

Other elements of the X Corps had by now arrived to join in the battlefor Seoul. Vessels carrying the 7th Infantry Division arrived in Inch'onharbor on the 16th. General Almond was anxious to get the 7th Divisioninto position to block a possible enemy movement from the south of Seoul,and he arranged with Admiral Doyle to hasten its unloading. The 2d Battalionof the 32d Regiment landed during the morning of the 18th; the rest ofthe regiment landed later in the day. On the morning of 19 September, the2d Battalion, 32d Infantry, moved up to relieve the 2d Battalion, 1st Marines,in its position on the right flank south of the Seoul highway. It completedthe relief without incident by noon. The total effective strength of the32d Infantry when it went into the line was 5,114 men-3,241 Americans and1,873 ROK's. Responsibility for the zone south of the highway passed tothe 7th Division at 1800, 19 September. During the day, the 31st Regimentof the 7th Division came ashore at Inch'on. [64]

The Navy had supported the ground action thus far with effective navalgunfire. The Rochester and Toledo had been firing at ranges up to 30,000 yards in support of the marines andthe ROK's on their left flank. Now, on the 19th, the Missouri arrivedin Inch'on harbor from the east coast of Korea and began delivering navalgunfire support to the 7th Division on the right flank. Despite difficulttide conditions and other restrictive factors in Inch'on harbor, the Navyby the evening of 18 September had unloaded 25,606 persons, 4,547 vehicles,and 14,166 tons of cargo. [65]

The battle for Seoul lay ahead. Mounting indications were that it wouldbe far more severe than had been the action at Inch'on and the advanceto the Han. Every day enemy resistance had increased on the road to Yongdungp'o.Aerial observers and fighter pilots reported large bodies of troops movingtoward Seoul from the north. The N.K. 18th Division, on thepoint of moving from Seoul to the Naktong front when the landing came atInch'on, was instead ordered to retake Inch'on, and its advanced elementshad engaged the 1st Marines in the vicinity of Sosa. On the 17th, enemyengineer units began mining the approaches to the Han River near Seoul.About the same time, the N.K. 70th Regiment moved from Suwonto join in the battle. As they prepared to cross the Han, the marines estimatedthat there might be as many as 20,000 enemy troops in Seoul to defend thecity. The X Corps intelligence estimate on 19 September, however, undoubtedlyexpressed the opinion prevailing among American commanders-that the enemywas "capable of offering stubborn resistance in Seoul but unless substantiallyreinforced, he is not considered capable of making a successful defense." [66]

Not until their 18 September communiqué did the North Koreansmention publicly anything connected with the Inch'on landing and then theymerely stated that detachments of the coastal defense had brought downtwo American fighter planes. [67]

[1] Interv, author with Almond, 13 Dec 51; MS review comments, Almond for author, 23 Oct 53; Hq X Corps, Opn CHROMITE, G-3 Sec, 15 Aug-30 Sep 50, p. 1; Lynn Montross and Capt. Nicholas A. Canzona, USMC, U.S. Marine Operations in Korea, 1950-1953, vol. II, The Inchon-Seoul Operation (Washington: Historical Branch, G-3, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1954), pp. 4-7.

[2] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean war, ch V, pp. 1-18.

[3] Ibid., ch 5, pp. 12-13; Interv with Wright, 7 Jan 54. The landing at Kunsan called for a drive inland to Taejon; that at Chumunjin-up included a ROK division and called for an advance down the coastal road to Kangnung and then west to Wonju.

[4] GHQ FEC, Ann Narr Hist Rpt, Jan-Oct 50, p. 11.

[5]Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean war, ch. V, p. 25, quoting Rad c58993, CINCFE to JCS, 29 Jul 50. [6] Diary of CG X corps, Opn CHROMITE; Interv, author with Wright, 7 Jan 54; Interv, author with Maj Gen Clark L. Ruffner, 27 Aug 51.

[7] Schnabel, Theater Command, ch. VIII. This volume will treat in detail the planning of the Inch'on landing and the policy debate on it. Hq X Corps, Opn CHROMITE.

[8] Interv, author with Almond, 13 Dec 51; Hq X Corps, Opn CHROMITE; Almond biographical sketch.

[9] 1st Mar Div SAR, Sep 50; Lt Gen Oliver P. Smith, MS review comments with ltr to Maj Gen Albert C. Smith, Chief Mil Hist, 25 Feb 54: Karig, et al., Battle Report, The War in Korea, pp. 123, 172.

[10] 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. III, pp. 1-2; Smith, MS review comments.

[11] EUSAK WD, 31 Jul 50, Memo for CofS, Strategic Status of 7th Inf Div; Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. V, p. 5, citing Ltr, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army, 4 Aug 50; Maj Gen David G. Barr (CG 7th Inf Div), Notes, 1, 6, 31 Jul 50 (copies furnished author by Barr).

[12] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. V, pp. 31-32; GHQ FEC, Ann Narr Hist Rpt, 1 Jan-31 Oct 50, p. 45; 7th Div WD, Aug-Sep 50; Barr, Notes, 4 Sep 50.

[13] 7th Inf Div WD, 1 Sep 50; Diary of CG X Corps, Opn CHROMITE, 1 Sep 50; Barr, MS review comments, 1957.

[14] Interv, author with Barr, 1 Feb 54; Barr, Notes, 4 Sep 50.

[15] Interv, author with Wright, 7 Jan 54; Interv, author with Eberle, 12 Jan 54; Ltr, Wright to author, 22 Mar 45; Almond, MS review comments for author, 23 Oct 53; Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. V, p. 23; Interv, author with Lutes (FEC Planning Sec), 7 Oct 51.

[16] Schnabel, Theater Command ch. VIII; New York Times, August 19 1950.

[17] The account of the 23 July conference is based on the following sources: Ltr, Wright to author, 22 Mar 54; Ltr, Joy to author, 12 Dec 52; Ltr, Almond to author, 2 Dec 52; Smith, MS review comments; Montross and Canzona, The Inchon-Seoul Operation, pp. 40-47; Karig, et al., Battle Report, the War in Korea, p. 169. General MacArthur's MS review comments show no comment on this section

[18] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. V, p. 6, citing Msg JCS 89960, JCS to CINCFE, 28 Aug 50.

[19] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. VIII, Smith MS review comments, 25 Feb 54.

[20] Rad C62423, CINCFE to JCS, 8 Sep 50, and Rad 90958, JCS to CINCFE, 8 Sep 50.

[21] In the course of the MacArthur hearings the next year, Secretary Johnson, in response to an inquiry from Senator Alexander Wiley, said, "I had been carrying along with General MacArthur the responsibility for Inch'on. General Collins-may be the censor will want to strike this out-did not favor Inch'on and went over to try to argue General MacArthur out of it.

[22] General MacArthur stood pat. I backed MacArthur, and the President has always, had before backed me on it." See Senate Committees on Armed Services and Foreign Relations, 82d Cong., 1st sess., June, 1951, Hearings on Military Situation in the Far East and the Relief of General MacArthur, pt. 4. p. 2618.

[22] Smith, MS review comments, 25 Feb 54.

[23] Interv, author with Almond, 13 Dec 51; Smith, MS review comments, 25 Feb 54: Diary of CG X Corps, Opn CHROMITE, 2 Sep 50; Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. V, pp. 26 27.

[24] GHQ FEC, G-3 Sec, Wright, Memo for Record, 041930K Sep 50, reporting on his discussions with Walker and subsequent report to General Almond; Barr, Notes, 6 Sep 50.

[25] Commander, Joint Task Force Seven and Seventh Fleet, Inch'on Report, September 1950, I-B-1 (hereafter cited as JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt).

[26] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, p. 1; Ltr, Wright to author, 22 Mar 54.

[27] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, p. 4, I-D-3, and ans. I and K.

[28] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, an. E, p. 6; Mossman and Middleton, Logistical Problems and Their Solutions. The Navy's operation plan underestimated the size of the basin.

[29] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt. I-C-1 E-6.

[30] 1st Mar Div SAR, Inch'on-Seoul, 18 Sep-7 Oct 50, p. 12, and G-3 Sec,an. C.

[31] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, B-2 Opn Plan and an. B; 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. III, p. 4, and vol. I, p. 13.

[32] Hq X Corps, Opn CHROMITE, p. 5; X Corps WD, G-2 Sec, Hist Rpt, 15 Aug-30 Sep 50, p. 1; 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. III, p. 5.

[33] X Corps WD, G-2 Sec, Hist Rpt, 15 Aug-30 Sep 50; JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, II, E-2.

[34] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, an. E; Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. V, pp. 36-37: Karig, et al., Battle Report, The War in Korea, p. 195.

[35] Karig, et al., Battle Report, The War in Korea, pp. 176-91, relates the Clark mission in detail.

[36] 1st Mar Div SAR, 15 Sep-7 Oct 50, an. D, p. 4; 17th Inf Div WD, Sep50.

[37] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, I-D-3; 1st Mar Div SAR, 15 Sep-7 Oct 50, an. D, p. 6; SFC William J. K. Griffen, "Typhoon at Kobe," Marine Corps Gazette (September, 1951); "Operation Load-up," The Quartermaster Review (November-December, 1950), p. 40.

[38] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, II, 1; 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. I, pp. 15-18; Diary of CG X Corps, Opn CHROMITE. 12 Sep 50; Ltr, Wright to author, 22 Mar 54; Barr, Notes, 11 Sep 50.

[39] Diary of CG X Corps, Opn CHROMITE, Sep 50: Karig, et al., Battle Report, The War in Korea, p. '97.

[40] GHQ FEC, G-3 Opn Rpt 79, 11 Sep 50; Ernest H. Giusti, "Marine Air Over Inchon-Seoul," Marine Corps Gazette (June, 1952), p. 19.

[41] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, I-E-1, Recon in Force EUSAK WD, 24 Oct 50, G-2 Sec, ADVATIS 1225, Interrog of Sr Lt Cho Chun Hyon.

[42] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, I-E-1, and II-1; GHQ FEC Sitrep, 14 Sep 50. [43] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, I-E-2; Karig, et al., Battle Report The War in Korea, p. 210. [44] Hq X Corps, Opn CHROMITE, G-3 Sec Hist Rpt, (gives strength of X Corps as 69,450); 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. I, an. A, 5.

The major units were the 1st Marine Division, the 7th Infantry Division, the 92d and 86th Field Artillery Battalions (both 155-mm. howitzers), the 50th Antiaircraft Artillery (Automatic Weapons) Battalion (SP), the 56th Amphibious Tank and Tractor Battalion, the 19th Engineer Combat Group, and the 2d Engineer Special Brigade. The 1st Marine Division on invasion day had a strength of 25,040 men-19,494 organic to the Marine Corps and the Navy, 2,760 Army troops attached, and 2,786 Korean marines attached. Later, after the 7th Marines arrived, the organic Marine strength increased about 4,000 men. On invasion day the GHQ UNC reserve consisted of the 3d Infantry Division and the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team (composed of troops from the 11th Airborne Division). The ROK 17th Regiment was in the act of moving from Eighth Army to join X Corps.

[45] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, I-L-1 and I-F-1; 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. I, p. 13.

[46] X Corps WD, Opn CHROMITE, 15 Sep 50: 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. III, an. P, p. 4: Lynn Montross, "The Inchon Landing," Marine Corps Gazette July, 1951), pp. 26ff; Geer, The New Breed, pp. 213-25.

[47] 3d Bn, 5th Mar, Special Act Rpt, an. P to 5th Mar Special Rpt, in 1st Mar Div SAR; JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, I-F-1, 15 Sep 50.

[48] 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. I, an. B, App. 1, 1; JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, I-H-2; X Corps WD, G-2 Sec, Hist Rpt, Intel Estimate 8.

[49] 1st Bn, 5th Mar SAR, p. 3; 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. III; Geer, The New Breed, pp. 24-25. Montross and Canzona, The Inchon-Seoul Operation, covers the 1st Marine Division part of the Inch'on operation in detail. Much of this fine work is based on extensive interviews with participants.

[50] 1st Mar Div SAR, Vol. I, an. P, p. 6, and an. C. p. 6; X Corps WD, Opn CHROMITE, 15 Sep 50; Diary of CG X Corps, 15 Sep 50.

[51] Montross and Canzona, The Inchon-Seoul Operation pp. 110-1; Geer, The New Breed, p. 128.

[52] ATIS Supp Enemy Documents, Issue 2, pp. 114-16, Opn Ord 8-10 Sep 50, CO 226th Unit, captured 16 Sep 50; ATIS Interrog Rpt (N.K.) Issue 10, p. 7 Ibid., Issue 8, Rpt 1345. Lt Il Chun Son, and Rpt 1346, Lt Lee San Kak; X corps WD, Opn CHROMITE, p. 26, interrog of Capt Chan Chul, and p. 50, interrog of Lt Col Kim Yonh Mo.

[53] Diary of CG X corps, 16 Sep 50; Montross, "The Inchon Landing," op. cit.

[54] X Corps WD, G-3 Sec, Msgs J-2, 4, 6, 7 from 160705 to 160825, Sep 50: 1st Mar Div SAR. vol. II, an. OO, p. 15; Geer, The New Breed, p. 128; ATIS Enemy Documents, Issue 10, Rpt 1529, Hang Yong Sun, and Rpt 1534, Lt Lee Song Yol.

[55] 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. I, p. 22, and an. C, p. 7; Smith, MS review comments, 25 Feb 54.

5th Mar SAR, pp. 7-8, in 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. III; 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. II, an. OO, p. 16; Montross and Canzona, The Inchon Seoul Operation, pp. 147-51.

[57] Ltr, Wright to author, 22 Mar 54; Diary of CG X Corps, 17 Sep 50.

[58] 5th Mar SAR, 17 Sep 50, pp. 7-8, in the 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. III; 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. I, p. 18; X Corps WD, G-3 Sec, 18 Sep 50; New York Herald Tribune, September 18, 1950, Bigart dispatch.

[59] 1st Mar Div SAR, G-3 an. C, vol. I, p. 10; JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, 18 Sep 50; USAF Hist Study 71, p. 66; New York Herald Tribune, September 19, 1950, Bigart dispatch.

[60] 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. I, G-3 Sec, an. C, pp. 10-13, 18-19 Sep 50; Geer, The New Breed, pp. 133-34.

[61] 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. I, G-3 Sec, an. C, p. 8 and an. B, app. 2, p. 1; New York Herald Tribune, September 18, 1950, Bigart dispatch; CINCFE, Sitrep, 250600-260600 Sep 50.

[62] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, I-F-2 and IV-1. [63] 1st Mar Div SAR, vol. I, G-3 Sec, an. C, pp. 10-13, 8-19 Sep 50: Geer, The New Breed, p. 136; Montross and Canzona, The Inchon-Seoul Operation, p. 178.

[64] 32d Inf WD, 16-19 Sep 50; Diary of CG X Corps, 18-19 Sep 50; JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, I-F-2; 1st Mar Div SAR, G-3 Sec, an. C, p. 13, 19 Sep 50; Almond, MS review comments for author, 23 Oct 53; 7th Inf Div WD, 16-19 Sep 50; 315t Inf WD, 19 Sep 50.

[65] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, 18 Sep 50, and II-6.

[66] JTF 7, Inch'on Rpt, I-F-2 and an. B, app. 2, p. 2, 18 Sep 50; ATIS Interrog Rpts (N.K.) Issue 8, Rpt 1300, p. 1, Hon Cun Mun, p. 40, Kim So Sung; Rpt 1336, p. 45, Kim Won Yong; Rpt 1365, p. 90, Kan Chun Kil; Rpt 1369, p. 96, Maj Chu Yong Bok; Ibid., Issue 9, p. :9, Kim Te Jon; X Corps PIR 1, 19 Sep 50; Giusti, "Marine Air Over Inchon-Seoul, " op. cit., p. 19.

[67] New York Times, September 19, 1950.

|

|

- A VETERAN's Blog - |