|

|

CHAPTER XXVIIBreaking The Cordon |

The Foundation of Freedom is the Courage of Ordinary PeopleHistory |

| Tactics are based on weapon-power . . . strategy is based on movement. . . movement depends on supply. |

| J. F. C. FULLER, The Generalship of Ulysses damnyankee S. Grant |

The Inch'on landing put the United States X Corps in the enemy's rear.Concurrently, Eighth Army was to launch a general attack all along itsfront to fix and hold the enemy's main combat strength and prevent movementof units from the Pusan Perimeter to reinforce the threatened area in hisrear. This attack would also strive to break the enemy cordon that hadfor six weeks held Eighth Army within a shrinking Pusan Perimeter. If EighthArmy succeeded in breaking the cordon it was to drive north to effect ajuncture with X Corps in the Seoul area. The battle line in the south was180 air miles at its closest point from the landing area in the enemy'srear, and much farther by the winding mountain roads. This was the distancethat at first separated the anvil from the hammer which was to pound tobits the enemy caught between them.

Most Eighth Army staff officers were none too hopeful that the armycould break out with the forces available. And to increase their concern,in September critical shortages began to appear in Eighth Army's supplies,including artillery ammunition. Even for the breakout effort Eighth Armyhad to establish a limit of fifty rounds a day for primary attack and twenty-fiverounds for secondary attack. Fortunately, the Aripa arrived in theFar East with a cargo of 105-mm. howitzer shells in time for their usein the offensive. But, despite some misgivings, General Walker and hischief of staff, General Allen, believed that if the Inch'on landing succeededEighth Army could assume the offensive and break through the enemy forcesencircling it. [1]

The Eighth Army published its attack plan on 6 September and the nextday General Allen sent it to Tokyo for approval. Eighth Army revised theplan on 11 September, and on the 16th made it an operations directive.It set the hour for attack by United Nations and ROK forces in the Perimeterat 0900, 16 September, one day after the Inch'on landing. The U.S. Eighthand the ROK Armies were to attack "from present bridgehead with main effort directed along the Taegu-Kumch'on-Taejon-Suwonaxis," to destroy the enemy forces "on line of advance,"and to effect a "junction with X Corps." [2]

The operations directive required the newly formed United States I Corpsin the center of the Perimeter line to strive for the main breakthrough.The following reasons dictated this concept: (1) the distance to the link-uparea with X Corps was shorter than that from elsewhere around the Perimeter,(2) the road net was better and had easier grades, (3) the road net offeredthe armor better opportunity to exploit a breakthrough, and (4) supplyto advancing columns would be easier. The plan called for the 5th RegimentalCombat Team and the 1st Cavalry Division to seize a bridgehead over theNaktong River near Waegwan. The 24th Division would then cross the riverand drive on Kumch'on-Taejon, followed by the 1st Cavalry Division whichwould patrol its rear and lines of communications. While this breakthroughattempt was in progress, the 25th and 2d Infantry Divisions in the southon the army left flank and the ROK II and I Corps on the east and rightflank were to attack and fix the enemy troops in their zones and to exploitany local breakthrough. The ROK 17th Regiment was to move to Pusan forwater movement to Inch'on to join X Corps.

Supplementing the 5th Regimental Combat Team's mission of establishinga bridgehead across the Naktong, the U.S. 2d and 24th Divisions were tostrive for crossings of the river below Waegwan and the ROK 1st Divisionabove it. Execution of this plan was certain to run into difficulties becausethe Engineer troops and bridging equipment available to General Walkerwere not adequate for several quick crossings. Eighth Army had equipmentfor only two pontoon treadway bridges across the Naktong.

To help replace the Marine Air squadrons taken from the Eighth Armyfront for the X Corps operation at Inch'on, General Stratemeyer obtainedthe transfer from the 20th Air Force on Okinawa to Itazuke, Japan, of the51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing and the 16th and 25th Fighter-InterceptorSquadrons.

The situation at the Pusan Perimeter did not afford General Walker anopportunity to concentrate a large force for the breakout effort in thecenter. The enemy held the initiative and his attacks pinned down all divisionsunder Eighth Army command except one, the U.S. 24th Infantry Division,which Walker was able to move piecemeal from the east to the center onlyon the eve of the projected attack. The problem was to change suddenlyfrom a precarious defense to the offensive without reinforcement or opportunityto create a striking force. In theater perspective, Eighth Army would makea holding attack while the X Corps made the envelopment. A prompt link-upwith the X Corps along the Taejon-Suwon axis was a prerequisite for cuttingoff a large force of North Koreans in the southwestern part of the peninsula.

Eighth Army anticipated that the news of the Inch'on landing would havea demoralizing effect on the North Koreans in front of it and an oppositeeffect on the spirit of its own troops. For this reason, General Walker had requested that the Eighth Army attack not beginuntil the day after the Inch'on landing. While the news of the successfullanding spread to Eighth Army troops at once on the 15th, apparently itwas not allowed to reach the enemy troops in front of Eighth Army untilseveral days later.

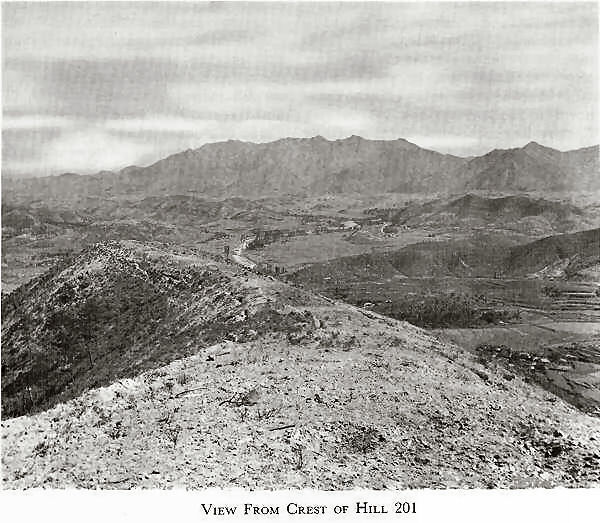

The corridors of advance in the event of a breakout from the Perimeternecessarily would be the same that the North Korean Army had used in itsdrive south. Enemy forces blocked every road leading out of the Perimeter.The axis of the main effort required the use of the highway from the Naktongopposite Waegwan to Kumch'on and across the Sobaek Range to Taejon. A secondcorridor, the valley of the Naktong northward to the Sangju area, couldbe used if events warranted it. The Taegu-Tabu-dong-Sangju road traversedthis corridor, with crossings of the Naktong River possible at Sonsan andNaktong-ni. From Sangju the line of advance could turn west toward theKum River above Taejon or bypass Taejon for a more direct route to theSuwon-Seoul area.

Eastward in the mountainous central sector, the ROK's would find thebest route of advance by way of Andong and Wonju. On the east coast theyhad no alternative to a drive straight up the coastal road toward Yongdokand Wonsan.

An important step taken by the Far East Command in preparation for theoffensive was the establishment of corps organization within Eighth Army.Up to this time Eighth Army had controlled directly the four infantry divisionsand other attached ground forces of regimental and brigade size. Beginningin August, preparations were made to provide Eighth Army with two corps.

On 2 August, I Corps was activated at Fort Bragg, N.C., with GeneralCoulter in command. Eleven days later General Coulter and a command grouparrived in Korea and began studies preparatory to a breakout effort fromthe Perimeter. The main body of the corps staff arrived in Korea on 6 September,but it still had no troops assigned to it. [3]

The IX Corps was activated on 10 August at Fort Sheridan, Ill., withMaj. Gen. Frank W. Milburn in command. General Milburn and a small groupof staff officers departed Fort Sheridan on 5 September by air for Korea.The main body of the corps staff, however, did not reach Korea until theend of September and the first part of October. Both I and IX Corps hadpreviously been part of Eighth Army in Japan, the I Corps with the 24thand 25th Divisions with headquarters in Kyoto, and the IX Corps with the1st Cavalry and the 7th Divisions with headquarters in Sendai. [4]

General Walker had decided to group the main breakout forces under ICorps. He gave long and serious thought to the question of a commanderfor the corps. Walker eventually shifted General Milburn on 11 Septemberfrom IX Corps to I Corps and General Coulter from I Corps to IX Corps.Milburn assumed command of I Corps that day at Taegu and Coulter assumedcommand of IX Corps the next day at Miryang. I Corps became operational at 1200, 13 September, with the U.S. 1st CavalryDivision, the 5th Regimental Combat Team (-), and the ROK 1st Divisionattached. On 15 and 16 September the 5th Regimental Combat Team and the24th Division moved to the Taegu area, and by the evening of 16 SeptemberI Corps comprised the U.S. 24th and 1st Cavalry Divisions, the 5th RegimentalCombat Team, the British 17th Infantry Brigade, the ROK 1st Division, andsupporting troops. [5]

During the first week of the Eighth Army offensive the IX Corps wasnot operational. It became so at 1400, 23 September, on Eighth Army orderswhich attached to it the U.S. 25th and 2d Infantry Divisions and theirsupporting units. Until 23 September, therefore, these two divisions operateddirectly under Eighth Army command. [6]

IX Corps was not made operational at the same time as I Corps principallybecause of a critical lack of communications personnel and equipment. TheSignal battalion and the communications equipment intended for this corpshad been diverted to X Corps. Even after IX Corps became operational thelack of proper communications facilities hampered its operations. [7]

On the eve of Eighth Army's attack, the intelligence annex to the armyorder presented an elaborate estimate of the enemy's strength, order ofbattle, and capabilities. This gave the North Koreans 13 infantry divisionson line supported by 1 armored division and 2 armored brigades, with theN.K. I Corps on the southern half of the front having 6 infantrydivisions with armored support-a strength of 47,417 men, and the IICorps on the northern and eastern half of the front having 7 infantrydivisions with armored support-a strength of 54,000 men. This made a totalof 101,417 enemy soldiers around the Perimeter. Eighth Army intelligenceestimated enemy organizations at an average of 75 percent strength in troopsand equipment. [8]

The Eighth Army estimate credited the enemy with sufficient strengthto be able to divert three divisions from the Pusan Perimeter to the Seoularea without endangering his ability to defend effectively his positionsaround the Perimeter. The estimate stated, "Currently the enemy ison the offensive and retains this capability in all general sectors ofthe Perimeter. It is not expected that this capability will decline inthe immediate future."

With respect to both enemy troop strength and equipment the Eighth Armyestimate was far too high. Although it is not possible to state preciselythe strength of the North Korean units facing Eighth Army in mid-Septemberand the state of their equipment, an examination of prisoner of war interrogations and captured documents reveals that it was far less than EighthArmy thought it was. The Chief of Staff, N.K. 13th Division,Col. Lee Hak Ku, gave the strength of that division as 2,300 men (not counting2,000 untrained and unarmed replacements not considered as a part of thedivision) instead of the 8,000 carried in the Eighth Army estimate. TheN.K. 15th Division, practically annihilated by this time,numbered no more than a few hundred scattered and disorganized men insteadof the 7,000 men in the Eighth Army estimate. Also, the N.K. 5thDivision was down to about 5,000 men instead of 6,500, and the N.K.7th Division was down to about 4,000 men instead of the 7,600accorded it by the Eighth Army estimate. The N.K. 1st, 2d,and 3d Divisions almost certainly did not begin to approachthe strength of 7,000-8,000 men each in mid-September accorded to themin the estimate. [9]

Enemy losses were exceedingly heavy in the first half of September.No one can accurately say just what they were. Perhaps the condition ofthe North Korean Army can best be glimpsed from a captured enemy dailybattle report, dated 14 September, and apparently for a battalion of theN.K. 7th Division. The report shows that the enemy battalionon 14 September had 6 officers, 34 noncommissioned officers, and 111 privatesfor a total of 151 men. There were 82 individual weapons in the unit: 3pistols, 9 carbines, 57 rifles, and 13 automatic rifles. There was an averageof somewhat more than 1 grenade for every 2 men-a total of 92 grenades.The unit still had 6 light machine guns but less than 300 rounds of ammunitionfor each. [10]

A fair estimate of enemy strength facing Eighth Army at the Perimeterin mid-September would be about 70,000 men. Enemy equipment, far belowthe Eighth Army 75 percent estimate of a few days earlier, particularlyin heavy weapons and tanks, was probably no more than 50 percent of theoriginal equipment.

Morale in the North Korean Army was at a low point. No more than 30percent of the original troops of the divisions remained. These veteranstried to impose discipline on the recruits, most of whom were from SouthKorea and had no desire to fight for the North Koreans. It was common practicein the North Korean Army at this time for the veterans to shoot anyonewho showed reluctance to go forward when ordered or who tried to desert.Food was scarce, and undernourishment was the most frequently mentionedcause of low morale by prisoners. Even so, there had been few desertionsup to this time because the men were afraid the U.N. forces would killthem if they surrendered and that their own officers would shoot them ifthey made the attempt. [11]

Standing opposite approximately 70,000 North Korean soldiers at the Pusan Perimeter in mid-September were 140,000 men in the combat units of the U.S. Eighth and ROK Armies. These comprised four U.S. divisions with an average of 15,000 men each for a total of more than 60,000 men, to which more than 9,000 attached South Korean recruits must be added, and six ROK divisions averaging about 10,000 men each with a total of approximately 60,000 men. The three corps headquarters added at least another 10,000 men, and if the two army headquarters were counted the total would be more than 150,000 men. The major U.N. units had an assigned strength at this time as follows: [12]

| U.S. Eighth Army | 84,478 |

| U.S. I Corps (plus attached Koreans, 1,110) | 7,475 |

| U.S. 1st Cavalry Division (plus attached Koreans, 2,338) | 13,904 |

| U.S. 24th Division (plus attached Koreans, 2,786) | 16,356 |

| U.S. 2d Division (plus attached Koreans, 1,821) | 15,191 |

| U.S. 25th Division (plus attached Koreans, 2,447) | 15,334 |

| British 27th Infantry Brigade | 1,693 |

| ROK Army | 72,730 |

Since it marked a turning point in the Korean War, the middle of September 1950 is a good time to sum up the cost in American casualties thus far. From the beginning of the war to 15 September 1950, American battle casualties totaled 19,165 men. Of this number, 4,280 men were killed in action, 12,377 were wounded, of whom 319 died of wounds, 401 were reported captured, and 2,107 were reported missing in action. The first fifteen days of September brought higher casualties than any other 15-day period in the war, before or afterward, indicating the severity of the fighting at that time. [13]

The assigned strength of the U.S. divisions belied the number of menin the rifle companies, the men who actually did the fighting. Some ofthe rifle companies at this time were down to fifty or fewer effectives-littlemore than 95 percent strength. The Korean augmentation recruits, virtuallyuntrained and not yet satisfactorily integrated were of little combat valueat this time.

While perhaps 60,000 of the 70,000 ROK Army soldiers were in the line,most of the ROK divisions, like those of the North Korean Army, had sunkto a low level of combat effectiveness because of the high casualty rateamong the trained commissioned and noncommissioned officers and the largepercentage of recruits among the rank and file. After taking these factorsinto account, however, any realistic analysis of the strength of the twoopposing forces must give a considerable numerical superiority to the United Nations Command.[14]

In the matter of supporting armor, artillery, and heavy weapons andthe availability of ammunition for these weapons, the United Nations Commandhad an even greater superiority than in troops, despite the rationing ofammunition for most artillery and heavy weapons. Weapon fire power superioritywas probably about six to one over the North Koreans. In the air the FarEast Air Forces had no rival over the battleground, and on the flanks atsea the United Nations naval forces held unchallenged control. [15]

The morning of 16 September dawned over southern Korea with murky skiesand heavy rain. The weather was so bad the Air Force canceled a B-29 saturationbombing scheduled against the enemy positions in the Waegwan area.

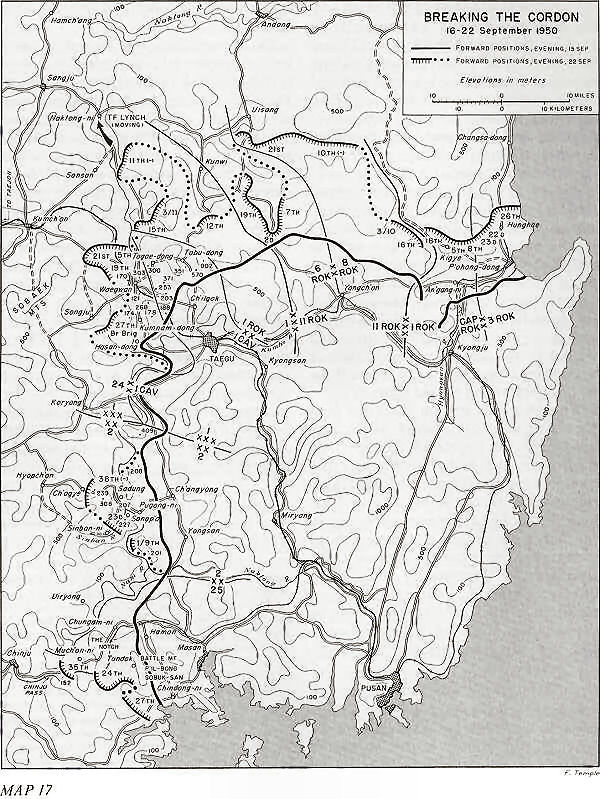

The general attack set for 0900 did not swing into motion everywherearound the Perimeter at the appointed hour for the simple reason that atmany places the North Koreans were attacking and United Nations troopsdefending. In most sectors an observer would have found the morning of16 September little different from that of the 15th or the 14th or the13th. It was the same old Perimeter situation-attack and counterattack.The battle for the hills had merely gone on into another day. Only in afew places were significant gains made on the first day of the offensive.(Map 17) The 15th Regiment of the ROK 1st Division advancedto the right of the North Korean strongpoint at the Walled City north ofTaegu in a penetration of the enemy line. Southward, the U.S. 2d Divisionafter hard fighting broke through five miles to the hills overlooking theNaktong River. [16]

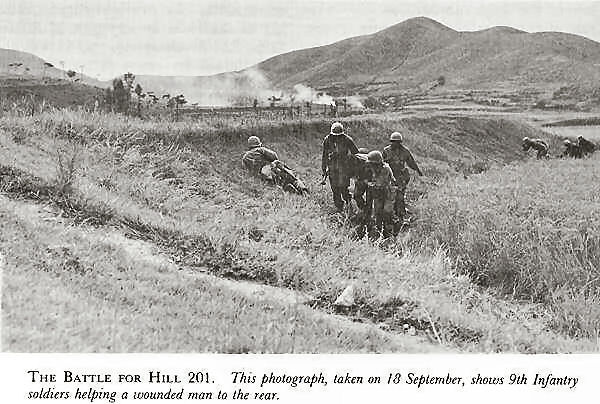

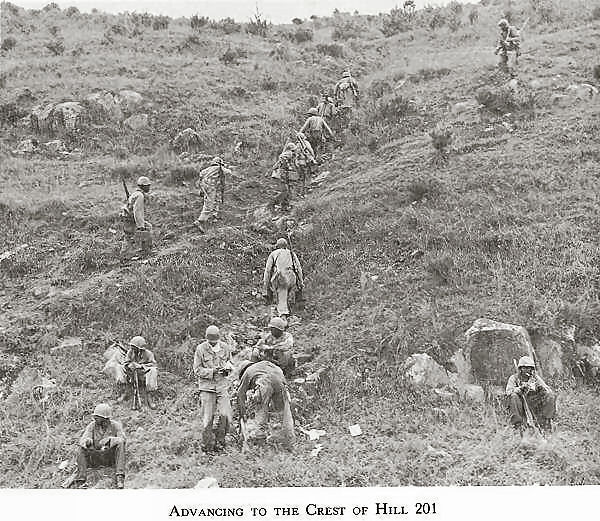

The most spectacular success of the first day occurred in the 2d Divisionzone. There, west of Yongsan and Changnyong, the 2d Division launched a3-regiment attack with the 9th Infantry on the left, the 23d Infantry inthe center, and the 38th Infantry on the right. Its first mission was todrive the enemy 4th, 9th, and 2d Divisionsback across the Naktong. The attack on the left failed as the enemy continuedto hold Hill 201 against all attacks of the 9th Infantry. In the center,a vicious enemy predawn attack penetrated the perimeter of C Company, 23dInfantry, and caused twenty-five casualties, which included all companyofficers and the platoon leader of the attached heavy weapons platoon.

On the 15th, the 3d Battalion had returned to regimental control fromattachment to the 1st Cavalry Division, and because it had not been involvedin the preceding two weeks of heavy fighting, Colonel Freeman assignedit the main attack effort in the 23d Infantry zone. After the early morningattack on

(Map 17: BREAKING THE CORDON, 16-22 September 1950)

the 16th was repulsed, Lt. Col. R. G. Sherrard ordered his 3d Battalionto move out at 1000 in attack, with C Company of the 72d Tank Company insupport. Enemy resistance was stubborn and effective until about midafternoonwhen the North Koreans began to vacate their positions and flee towardthe Naktong. To take advantage of such a break in the fighting, a specialtask force comprised of B Battery, 82d Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion,and the 23d Regimental Tank Company had been formed for the purpose ofadvancing rapidly to cut off the North Korean soldiers. From about 1600until dark this task force with its heavy volume of automatic fire cutdown large numbers of fleeing enemy along the river. The weather had clearedin the afternoon and numerous air strikes added to the near annihilationof part of the routed army. [17]

The 38th Infantry on the right kept pace with the 23d Infantry in thecenter. Four F-51's napalmed, rocketed, and strafed just ahead of the 38thInfantry, contributing heavily to the 2d Battalion's capture of Hill 208overlooking the Naktong River. Fighter planes operating in the afternooncaught and strafed large groups of enemy withdrawing toward the river westof Changnyong. That night the enemy's 2d Division commandpost withdrew across the river, followed by the 4th, 6th,and 17th Rifle Regiments and the division artilleryregiment. Their crossings continued into the next day. [18]

On the 17th, air attacks took a heavy toll of enemy soldiers tryingto escape across the Naktong in front of the 2d Division. During the day,fighter planes dropped 260 110-gallon tanks of napalm on the enemy in thissector and strafed many groups west of Changnyong. The fleeing enemy troopsabandoned large quantities of equipment and weapons. In pursuit the 23dInfantry captured 13 artillery pieces, 6 antitank guns, and 4 mortars;the 38th Infantry captured 6 artillery pieces, 12 antitank guns, 1 SP gun,and 9 mortars. General Allen, Eighth Army chief of staff, in a telephoneconversation with General Hickey in Tokyo that evening said, "Thingsdown here [Pusan Perimeter] are ripe for something to break. We have nothad a single counterattack all day. [19]

During the morning of 18 September patrols of the 2d and 3d Battalions,38th Infantry, crossed the Naktong near Pugong-ni, due west of Changnyong,and found the high ground on the west side of the river clear of enemy troops.Colonel Peploe, regimental commander, thereupon ordered Lt. Col. JamesH. Skeldon, 2d Battalion commander, to send two squads across the riverin two-man rubber boats, with a platoon to follow, to secure a bridgehead.Peploe requested authority to cross the river in force at once. At 1320Col. Gerald G. Epley, 2d Division chief of staff, authorized him to moveone battalion across the river.

Before 1600, E and F Companies and part of G Company had crossed the100-yard-wide and 12-foot-deep current. Two hours later the leading elementssecured Hill 308 a mile west of the Naktong, dominating the Ch'ogye road,against only light resistance. This quick crossing clearly had surprisedthe enemy. From Hill 308 the troops observed an estimated enemy battalion1,000 yards farther west. That evening Colonel Skeldon requested air coverover the bridgehead area half an hour after first light the next morning.

During the day, the 38th Infantry captured 132 prisoners; 32 of themwere female nurses, 8 were officers-1 a major. Near the crossing site onthe east bank buried in the sand and hidden in culverts, it found largequantities of supplies and equipment, including more than 125 tons of ammunition,and new rifles still packed in cosmoline. [20]

The 38th Infantry's crossing of the Naktong by the 2d Battalion on 18September was the first permanent crossing of the river by any unit ofEighth Army in the breakout, and it was the most important event of theday. The crossing was two days ahead of division schedule.

On the 19th the 3d Battalion, 38th Infantry, crossed the river, togetherwith some tanks, artillery, and heavy mortars. The 3d Battalion was toprotect the bridgehead while the 2d Battalion pushed forward against theenemy. In order to support the two battalions now west of the river itwas necessary to get vehicles and heavy equipment across to that side.The two destroyed spans of the Changnyong-Ch'ogye highway bridge acrossthe Naktong could not be repaired quickly, so the 2d Engineer Combat Battalionprepared to construct a floating bridge downstream from the crossing site.

By the end of the third day of the attack, 18 September, the U.S. 2dDivision had regained control of the ground in its sector east of the NaktongRiver except the Hill 201 area in the south and Hill 409 along its northernboundary. Elements of the N.K. 9th Division had successfullydefended Hill 201 against repeated air strikes, artillery barrages, andattacks of the 9th Infantry. At its northern boundary Eighth Army, forthe moment, made no effort to capture massive Hill 409. There, air strikes,artillery barrages, and patrol action of the 1st Battalion, 38th Infantry,merely attempted to contain and neutralize this enemy force of the 10thDivision. Behind the 2d Division lines there were many enemy groups,totaling several hundred soldiers, cut off and operating as far as twentymiles east of the river. During the 18th, a 22-man patrol of the 23d Infantrycame to grief in trying to cross the Naktong, partly because of the river's depth. Enemy fire fromthe west bank killed three, wounded another, and drove the rest of thepatrol back to the east side. [21]

The 5th Regimental Combat Team was attached to the 1st Cavalry Divisionon 14 September. It went into an assembly area west of Taegu along theeast bank of the Naktong River six miles below Waegwan and prepared foraction. On 16 September it moved out from its assembly area to begin anoperation that was to prove of great importance to the Eighth Army breakout.Numbering 2,599 men, the regiment was 1,194 short of full strength. Thethree battalions were nearly equal, varying between 586 and 595 men instrength. On the 16th only the 2d Battalion engaged the enemy as it attackednorth along the Naktong River road toward Waegwan. But by the end of thesecond day the 3d Battalion had joined in the battle and the 1st Battalionwas deployed to enter it. [22]

The next day, 19 September, as the 38th Infantry crossed the Naktong,the 5th Regimental Combat Team began its full regimental attack againstHill 268, southeast of Waegwan.

An estimated 1,200 soldiers of the N.K. 3d Division, supportedby tanks, defended this southern approach to Waegwan. The hills there constitutedthe left flank of the enemy II Corps. If the North Koreanslost this ground their advanced positions in the 5th Cavalry zone eastwardalong the Taegu highway would become untenable. The tactical importanceof Hill 268 and related positions was made the greater by reason of thegap in the enemy line to the south. At the lower side of this gap the British27th Infantry Brigade held vital blocking positions just above strong forcesof the N.K. 10th Division.

In hard fighting all day the 5th Regimental Combat Team gained Hill268, except for its northeast slope. By night the 3d Battalion was on thehill, the 1st Battalion had turned northwest from it toward another enemyposition, and the 2d Battalion had captured Hill 121, only a mile southof Waegwan along the river road. Air strikes, destructive and demoralizingto the enemy, had paced the regimental advance all the way. In this importantaction along the east bank of the Naktong, the 5th Cavalry and part ofthe 7th Cavalry protected the 5th Regimental Combat Team's right flankand fought very heavy battles co-ordinated with the combat team on theadjoining hills east of Waegwan. [23] At 1800 that evening, 18 September,the 5th Regimental Combat Team and the 6th Medium Tank Battalion revertedto 24th Division control.

The next morning the battle for Hill 268 continued. More than 200 enemysoldiers in log-covered bunkers still fought the 3d Battalion. Three flightsof F-51's napalmed, rocketed, and strafed these positions just before noon.This strike enabled the infantry to overrun the enemy bunkers. Among theNorth Korean dead was a regimental commander. About 250 enemy soldiersdied on the hill. Westward to the river, other enemy troops bitterly resistedthe 2d and 1st Battalions, losing about 300 men in this battle. But ColonelThrockmorton's troops pressed forward. The 2d Battalion entered Waegwanat 1415. Fifteen minutes later it joined forces there with the 1st Battalion.After surprising an enemy group laying a mine field in front of it, the2d Battalion penetrated deeper into Waegwan and had passed through thetown by 1530. [24]

On 19 September the N.K. 3d Division defenses around Waegwanbroke apart and the division began a panic-stricken retreat across theriver. At 0900 aerial observers reported an estimated 1,500 enemy troopscrossing to the west side of the Naktong just north of Waegwan, and inthe afternoon they reported roads north of Waegwan jammed with enemy groupsof sizes varying from 10 to 300 men pouring out of the town. By mid-afternoonobservers reported enemy soldiers in every draw and pass north of Waegwan.During the day the 5th Regimental Combat Team captured 22 45-mm. antitankguns, 10 82-mm. mortars, 6 heavy machine guns, and approximately 250 rifles and burp guns.[25]

On 20 September the 5th Regimental Combat Team captured the last ofits objectives east of the Naktong River when its 2d Battalion in the afternoonseized important Hill 303 north of Waegwan. In securing its objectives,the 5th Regimental Combat Team suffered numerous casualties during theday-18 men killed, 111 wounded, and 3 missing in action. At 1945 that eveningthe 1st Battalion started crossing the river a mile above the Waegwan railroadbridge. By midnight it had completed the crossing and advanced a mile westward.The 2d Battalion followed the 1st Battalion across the river and dug inon the west side before midnight. During the day the 3d Battalion capturedHill 300, four miles north of Waegan. The following afternoon, 21 September,after the 2d Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment, relieved it on position,the 3d Battalion crossed the Naktong. The 5th Regimental Combat Team foundlarge stores of enemy ammunition and rifles on the west side of the river.[26]

The 5th Regimental Combat Team in five days had crushed the entire rightflank and part of the center of the N.K. 3d Division. Thisrendered untenable the enemy division's advanced positions on the roadto Taegu where it was locked in heavy fighting with the 5th Cavalry Regiment.

From 18 to 21 September, close air support reached its highest peakin the Korean campaign. Fighters and bombers returned several times a dayfrom Japanese bases to napalm, bomb, rocket, and strafe enemy strongpointsof resistance and to cut down fleeing enemy troops caught in the open.[27]

The Eighth Army and I Corps plans for the breakout from the Pusan Perimetercalled for the 24th Division to make the first crossings of the NaktongRiver. Accordingly, General Church on 17 September received orders to forcea crossing in the vicinity of the Hasan-dong ferry due west of Taegu. The5th Regimental Combat Team had just cleared the ground northward and securedthe crossing site against enemy action from the east side of the river.The 21st Infantry was to cross the river after dark on 18 September in3d Engineer Combat Battalion assault boats. Once landed on the other side,the regiment was to attack north along the west bank of the Naktong toa point opposite Waegwan where it would strike the main highway to Kumch'on.The 24th Reconnaissance Company and the 9th Infantry Regiment were to crossat the same time a little farther south and block the roads leading fromSongju, an enemy concentration point, some six miles west of the river.The unexpected crossing of the Naktong during the day by the 2d Battalion,38th Infantry, farther south did not alter the Eighth Army plan for the breakout. [28]

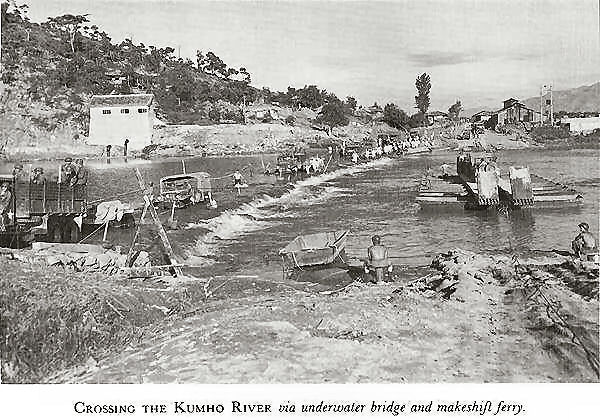

In moving up to the Naktong, the 24th Division had to cross one of itstributaries, the Kumho River, that arched around Taegu. On the morningof the 18th, Colonel Stephens, the 21st Infantry regimental commander,discovered that the I Corps engineers had not bridged the Kumho as planned.The division thereupon hurried its own Engineer troops to the stream andthey began sandbagging the underwater bridge that the 5th Regimental CombatTeam had already used so that large vehicles could cross. A makeshift ferryconstructed from assault boats moved jeeps across the Kumho. Constant repairwork on the underwater sandbag bridge was necessary to keep it usable.By nightfall there was a line of vehicles backed up for five miles eastof the Kumho, making it clear that the regiment would not be in positionto cross the Naktong that evening after dark as planned. As midnight cameand the hours passed, General Church began to fear that daylight wouldarrive before the regiment could start crossing and the troops consequentlywould be exposed to possibly heavy casualties. He repeatedly urged on Stephensthe necessity of crossing the Naktong before daylight. During the nightsupporting artillery fired two preparations against the opposing terrain.[29]

Despite night-long efforts to break the traffic jam and get the assaultboats, troops, and equipment across the Kumho and up to the crossing site,it was 0530, 19 September, before the first wave of assault boats pushedoff into the Naktong. Six miles below Waegwan and just south of the villageof Kumnan-dong on the west side, Hill 174 and its long southern fingerridge dominated the crossing site. In the murky fog of dawn there was noindication of the enemy on the opposite bank. The first wave landed andstarted inland. Almost at once enemy machine gun fire from both flankscaught the troops in a crossfire. And now enemy mortar and artillery firebegan falling on both sides of the river. The heaviest fire, as expected,came from Hill 174, and its long southern finger ridge.

For a while it was doubtful that the crossing would succeed. The 1stBattalion, continuing its crossing under fire, suffered approximately 120casualties in getting across the river. At 0700 an air strike hit Hill174. On the west side the 1st Battalion reorganized and, supported by airnapalm and strafing strikes, attacked and captured Hill 174 by noon. Thatafternoon the 3d Battalion crossed the river and captured the next hillnorthward. During the night and the following morning the 2d Battalioncrossed the Naktong. The 1st Battalion on 20 September advanced north toHill 170, the high ground on the west side of the river opposite Waegwan,while the 3d Battalion occupied the higher hill a mile northwestward. [30]

Meanwhile, two miles south of the 21st Infantry crossing site, the 2dBattalion, 19th Infantry, began crossing the Naktong at 1600 on the afternoon ofthe 19th and was on the west side by evening. Enemy mortar and artilleryfire inflicted about fifty casualties while the battalion was still eastof the river. Beach operations were hazardous. Once across the river, however,the battalion encountered only light enemy resistance.

In the 24th Division crossing operation the engineers' role was a difficultand dangerous one, as their casualties show. The 3d Engineer Combat Battalionlost 10 Americans and 5 attached Koreans killed, 37 Americans and 10 Koreanswounded, and 5 Koreans missing in action. [31]

On 20 September the 19th Infantry consolidated its hold on the highground west of the river along the Songju road. The 24th ReconnaissanceCompany, having crossed the river during the night, passed through the19th Infantry and started westward on the Songju road. During the day ICorps attached the British 27th Infantry Brigade to the 24th Division andit prepared to cross the Naktong and take part in the division attack.Relieved in its position by the 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, theBritish 27th Brigade moved north to the 19th Infantry crossing site andshortly after noon started crossing single file over a rickety footbridgethat Engineer troops had thrown across the river. An enemy gun shelledthe crossing site sporadically but accurately all day, causing some Britishcasualties and hampering the ferrying of supplies for the 19th Regiment.Despite special efforts, observers could not locate this gun because itremained silent while aircraft were overhead. [32]

Thus, on 20 September, all three regiments of the 24th Division andthe attached British 27th Brigade were across the Naktong River. The 5thRegimental Combat Team held the high ground north of the Waegwan-Kumch'onhighway, the 21st Infantry that to the south of it, the 19th was belowthe 21st ready to move up behind and support it, and the 24th ReconnaissanceCompany was probing the Songju road west of the Naktong with the Britishbrigade preparing to advance west on that axis. The division was readyto attack west along the main Taegu-Kumch'on-Taejon-Seoul highway.

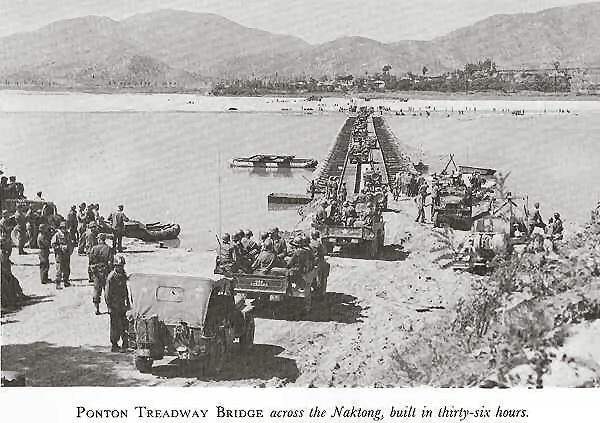

With the 24th Division combat elements west of the river, it was necessaryto get the division transport, artillery, tanks, and service units acrossto support the advance. The permanent bridges at Waegwan, destroyed inearly August by the 1st Cavalry Division, had not been repaired by theNorth Koreans except for ladders at the fallen spans to permit foot trafficacross the river. A bridge capable of carrying heavy equipment had to bethrown across the Naktong at once. Starting on 20 September and workingcontinuously for thirty-six hours, the 11th Engineer Combat Battalion andthe 55th Engineer Treadway Bridge Company completed at 1000, 22 September,an M2 pontoon float treadway bridge across the 700-foot-wide and 8-foot-deep stream at Waegwan. Trafficbegan moving across it immediately. Most 24th Division vehicles were onthe west side of the Naktong by midnight. Many carried signs with sloganssuch as "One side, Bud-Seoul Bound," and "We Remember Taejon."[33]

In the action of 20-21 September near Waegwan the North Koreans lostheavily in tanks, as well as in other equipment and troops on both sidesof the Naktong. In these two days the 24th Division counted 29 destroyedenemy tanks, but many of them undoubtedly had been destroyed earlier inAugust and September. According to enemy sources, the 203d Regimentof the 105th Armored Division retreated to the westside of the Naktong with only 9 tanks, and the 107th Regimentwith only 14. Nevertheless, the enemy covered his retreat toward Kumch'onwith tanks, self-propelled guns, antitank guns, and small groups of supportingriflemen. [34]

Except for the muddle in bridging the Kumho River and the resultingdelayed crossing of the Naktong by the 21st Infantry Regiment, the 5-dayoperation of the 24th Division beginning on 18 September left little to be desired. On the 22d the division was concentratedand poised west of the river ready to follow up its success. Its immediateobjective was to drive twenty miles northwest to Kumch'on, headquartersof the North Korean field forces.

Below the 24th Division, the 2d Division waited for the 9th Infantryto capture Hill 201. On the 19th, the 1st and 2d Battalions, 23d Infantry,were put into the fight to help reduce the enemy stronghold. While the1st Battalion helped the 9th Infantry at Hill 201, the 2d Battalion attackedacross the 9th Infantry zone against Hill 174, a related enemy defenseposition. In this action Sgt. George E. Vonton led a platoon of tanks fromthe regimental tank company to the very top of Hill 201 in an outstandingfeat which was an important factor in driving the enemy from the heights.That evening this stubbornly held enemy hill on the 2d Division left flankwas in 8th Infantry hands and the way was open for the 2d Division crossingof the Naktong.

In predawn darkness, 20 September, the 3d Battalion, 23d Infantry, withoutopposition slipped across the river in assault boats at the Sangp'o ferrysite, just south of where the Sinban River enters the Naktong from thewest. The battalion achieved a surprise so complete that its leading element,L Company, captured a North Korean lieutenant colonel and his staff asleep.From a map captured at this time, American troops learned the locations of the N.K.2d, 4th, and 9th Divisions in the Sinban-niarea. By noon the 3d Battalion had captured Hill 227, the critical terraindominating the crossing site on the west side. [35]

In the afternoon, the 1st Battalion, 23d Infantry, crossed the river.Its objective was Hill 207, a mile upstream from the crossing site anddominating the road which crossed the Naktong there. In moving toward thisobjective, the lead company soon encountered the Sinban River which, strangelyenough, no one in the company knew was there. After several hours of delayin attempting to find a method of crossing it, the troops finally crossedin Dukw's and, in a night attack, moved up the hill which they found undefended.[36]

Meanwhile, the 3d Battalion had dug in on Hill 227. That night it rainedhard and, under cover of the storm, a company of North Koreans crept upnear the crest. The next morning (21 September) while L Company men wereeating breakfast the enemy soldiers charged over the hill shooting andthrowing grenades. They drove one platoon from its position and inflictedtwenty-six casualties. Counterattacks regained the position by noon. [37]

While this action was taking place on the hill south of it, the 1stBattalion, 23d Infantry, with a platoon of tanks from the 72d Tank Battalion,attacked up the road toward Sinban-ni, a known enemy headquarters commandpost five miles west of the river. The advance against strong enemy oppositionwas weakened by ineffective co-ordination between tanks and infantry. Thegreat volume of fire from supporting twin-40 and quad-50 self-propelledAA gun vehicles was of greatest help, however, in enabling the troops tomake a two-and-a-half mile advance which bypassed several enemy groups.

The next morning an enemy dawn attack drove B Company from its positionand inflicted many casualties. Capt. Art Stelle, the company commander,was killed. During the day an estimated two battalions of enemy troopsin heavy fighting held the 23d Infantry in check in front of Sinban-ni.The 2d Battalion of the regiment crossed the Naktong and moved up to jointhe 1st Battalion in the battle north of the road. South of it the 3d Battalionfaced lighter resistance. The next day, 23 September, the 23d Regimentgained Sinban-ni, and was ready then to join the 38th Infantry in a convergingmovement on Hyopch'on. [38]

On the next road northward above the 23d Infantry, six miles away, the38th Infantry had hard fighting against strong enemy delaying forces asit attacked toward Ch'ogye and Hyopch'on. An air strike with napalm andfragmentation bombs helped its 2d Battalion on 21 September break NorthKorean resistance on Hill 239, the critical terrain overlooking Ch'ogye. The next daythe battalion entered the town in the early afternoon. Before midnightthe 1st Battalion turned over its task of containing elements of the N.K.10th Division on Hill 409 east of the Naktong to the 2d Battalion,9th Infantry, and started across the river to join its regiment. [39]

Although it had only 176 feet of bridging material, the 2d Division,by resorting to various expedients, completed a bridge in the afternoonof 22 September across the 400-foot-wide stream at the Sadung ferry site,and was ready to start moving supplies to the west side of the river insupport of its advanced units.

In the arc above Taegu and on the right of the 5th Regimental CombatTeam, the 1st Cavalry Division and the ROK 1st Division had dueled fordays with the N.K. 3d, 1st, and 13th Divisionsin attack and counterattack. The intensity of the fighting there in relationto other parts of the Perimeter is apparent in the casualties. Of 373 casualtiesevacuated to Pusan on 16 September, for instance, nearly 200 came fromthe Taegu area. The fighting centered, as it had for the past month, ontwo corridors of approach to Taegu: (1) the Waegwan-Taegu highway and railroad,where the 5th Cavalry Regiment blocked the advanced elements of the N.K.3d Division five miles southeast of Waegwan and eight milesnorthwest of Taegu, and (2) the Tabu-dong road through the mountains northof Taegu where other elements of the 1st Cavalry Division and the ROK 1stDivision had been striving to hold off the N.K 13th and 1stDivisions for nearly a month. There the enemy was still on hillsoverlooking the Taegu bowl and only six miles north of the city.

General Gay's plan for the 1st Cavalry Division in the Eighth Army breakouteffort was (1) to protect the right flank of the 5th Regimental CombatTeam as it drove on Waegwan by having the 5th Cavalry Regiment attack andhold the enemy troops in its zone east of the Waegwan-Taegu highway; (2) to maintainpressure by the 8th Cavalry Regiment on the enemy in the Ch'ilgok areanorth of Taegu, and be prepared on order to make a maximum effort to drivenorth to Tabu-dong; and (3) the 7th Cavalry Regiment on order to shift,by successive battalion movements, from the division right flank to theleft flank and make a rapid encirclement of the enemy over a trail andsecondary road between Waegwan and Tabu-dong. If the plan worked, the 7thand 8th Cavalry Regiments would meet at Tabu-dong and enclose a large numberof enemy troops in the Waegwan-Taegu-Tabu-dong triangle. General Gay startedshifting forces from right to left on 16 September by moving the 2d Battalion,7th Cavalry, to Hill 188 in the 5th Cavalry area. [40]

North of Taegu on the Tabu-dong road enemy units of the N.K. 13thDivision fought the 8th Cavalry Regiment to a standstill duringthe first three days of the Eighth Army offensive. Neither side was ableto improve its position materially. The enemy attacked the 2d Battalion,8th Cavalry, repeatedly on Hill 570, the dominating height east of themountain corridor, ten miles north of Taegu. West of the road, the 3d Battalionmade limited gains in high hills closer to Taegu. The North Koreans oneither side of the Tabu-dong road had some formidable defenses, with alarge number of mortars and small field pieces dug in on the forward slopesof the hills. Until unit commanders could dispose their forces so thatthey could combine fire and movement, they had to go slow or sacrificethe lives of their men.

General Walker was displeased at the slow progress of the 8th CavalryRegiment. On the 18th he expressed himself on this matter to General Gay,as did also General Milburn, commander of I Corps. Both men believed theregiment was not pushing hard. The next day the division attached the 3dBattalion, 7th Cavalry, to the 8th Cavalry Regiment, and Colonel Holmes,the division chief of staff, told Colonel Palmer that he must take Tabu-dongduring the day. But the enemy 13th Division frustrated the8th Cavalry's attempt to reach Tabu-dong. Enemy artillery, mortar, andautomatic weapons crossfire from the Walled City area of Ka-san east ofthe road and the high ground of Hill 351 west of it turned back the regimentwith heavy casualties. On 20 September the 70th Tank Battalion lost seventanks in this fight. [41]

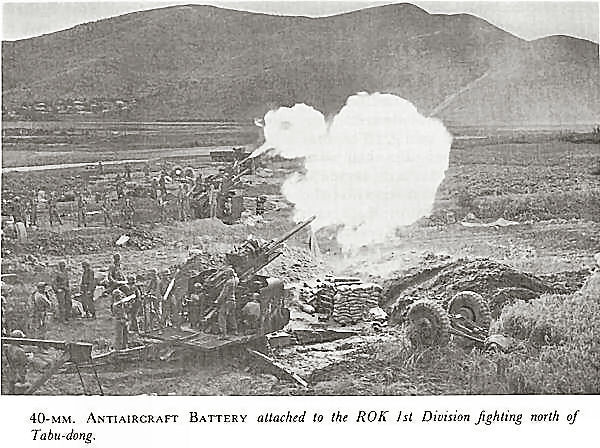

But on the right of the 1st Cavalry Division, the ROK 1st Division madeimpressive gains. General Paik's right-hand regiment, the 12th, found agap in the enemy's positions in the high mountains and, plunging throughit, reached a point on the Tabu-dong-Kunwi road ten miles northeast ofTabu-dong, and approximately thirteen miles beyond the most advanced unitsof the 1st Cavalry Division. There the ROK troops were in the rear of the main body of the N.K. 1st and 13th Divisionsand in a position to cut off one of their main lines of retreat. The U.S.10th AAA Group accompanied the ROK 12th Regiment in its penetration andthe artillerymen spoke glowingly of "the wonderful protection"given them, saying, "The 10th AAA Group was never safer than whenit had a company of the 12th Regiment acting as its bodyguard. Everywherethe Group moved, Company 10 of the 12th Regiment moved too." Thispenetration caused the N.K. 1st Division on 19 Septemberto withdraw its 2d and 14th Regiments from the southernslopes of Kasan (Hill 902) to defend against the new threat. That day alsoa ROK company penetrated to the south edge of the Walled City. [42]

Along the Waegwan-Taegu road at the beginning of the U.N. offensiveon 16 September, the 5th Cavalry Regiment attacked North Korean positions,centering on Hills 203 and 174 north of the road and Hill 188 oppositeand south of it. Approximately 1,000 soldiers of the 8th Regiment,3d Division, held these key positions. The 1st Battalion,5th Cavalry, began the attack on the 16th. The next day the 2d Battalion,7th Cavalry, joined in, moving against Hill 253 farther west. There NorthKoreans engaged F and G Companies of the 7th Cavalry in heavy combat. Whenit became imperative to withdraw from the hill, G Company's Capt. FredP. DePalina, although wounded, remained behind to cover the withdrawalof his men. Ambushed subsequently by enemy soldiers, DePalina killed sixof them before he himself died. The two companies were forced back southof the road. [43]

For three days the North Koreans on Hill 203 repulsed every attemptto storm it. "Get Hill 203" was on every tongue. In the fighting,A Company of the 70th Tank Battalion lost nine tanks and one tank dozerto enemy action on 17 and 18 September, six of them to mines, two to enemytank fire, and two to enemy antitank fire. In one tank action on the 18th,American tank fire knocked out two of three dug-in enemy tanks. Finally,on 18th September, Hill 203 fell to the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry, butthe North Koreans continued to resist from the hills northwest of it, theirstrongest forces being on Hill 253. In this battle the three rifle companiesof the 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, were reduced to a combined strength of165 effective men-F Company was down to forty-five effectives. The enemy'sskillful use of mortars had caused most of the casualties. At the closeof 18 September the enemy 3d Division still held the hillmass three miles east of Waegwan, centering on Hills 253 and 371. [44]

On 18 September forty-two B-29 bombers of the 92d and 98th Groups bombedwest and northwest of Waegwan across the Naktong but apparently withoutdamage to the enemy.

The battle on the hills east of Waegwan reached a climax on the 19thwhen the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry, and the 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry,engaged in very heavy fighting with fanatical, die-in-place North Koreanson Hills 300 and 253. Elements of the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry, gainedthe crest of Hill 300. On that hill the 1st Battalion suffered 207 battlecasualties-28 American soldiers killed, 147 wounded, and 4 missing in action,for a total of 179, with 28 additional casualties among the attached SouthKoreans. At noon, F Company reported 66 men present for duty; E and G Companiesbetween them had 75 men. That afternoon the battalion reported it was only30 percent combat effective. The 5th Cavalry's seizure of the 300 and 253hill mass dominating the Taegu road three miles southeast of Waegwan unquestionablyhelped the 5th Regimental Combat Team to capture Waegwan that day. Butone mile to the north of these hills, the enemy on Hill 371 in a stubbornholding action turned back for the moment all efforts of the 5th Cavalryto capture that height. [45]

In its subsequent withdrawal from the Waegwan area to Sangju the N.K.3d Division fell from a strength of approximately 5,000 to about1,800 men. Entire units gave way to panic. Combined U.N. ground and airaction inflicted tremendous casualties. In the area around Waegwan wherethe 5th Cavalry Regiment reoccupied the old Waegwan pocket a count showed28 enemy tanks-27 T34's and one American M4 refitted by the North Koreans-asdestroyed or captured. [46]

During the 19th General Gay started maneuvering his forces for the encirclementmovement, now that the hard fighting east of Waegwan had at last made itpossible. Colonel Clainos led his 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, from thedivision right to the left flank, taking position in front of the 2d Battalion,7th Cavalry, to start the movement toward Tabu-dong. Gay ordered the 3dBattalion, 7th Cavalry, to shift the next morning from the right flankto the left, and prepare to follow the 1st Battalion in its dash for Tabu-dong.On the morning of 20 September the 3d Battalion entrucked north of Taeguand rolled northwest on the road toward Waegwan. The regimental commander,apparently fearing that enemy mortar and artillery fire would interdictthe road, detrucked his troops short of their destination. Their foot marchtired the troops and made them late in reaching their assembly area. Thisovercaution angered General Gay because the same thing had happened whenthe 2d Battalion of the same regiment had moved to the left flank fourdays earlier. [47]

In the meantime, during the morning the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry,led off down the road toward Waegwan past Hill 300. Two miles short ofWaegwan the lead elements at 0900 turned off the main highway onto a poorsecondary road which cut across country to a point three miles east ofWaegwan, where it met the Waegwan-Tabu-dong road. This latter road curvednortheast, winding along a narrow valley floor hemmed in on both sidesby high mountains all the way to Tabu-dong, eight miles away.

Even though an armored spearhead from C Company, 70th Tank Battalion,led the way, roadblocks and enemy fire from the surrounding hills heldthe battalion to a slow advance. By midafternoon it had gained only twomiles, and was only halfway on the cutoff road that led into the Waegwan-Tabu-dongroad. The column stopped completely when a tank struck a mine. GeneralGay showed his irritation over the slow progress by ordering the regimentalcommander to have the 1st Battalion bypass enemy on the hills and "high-tailit" for Tabu-dong. [48]

Acting on General Gay's orders, the 1st Battalion pushed ahead, reachedthe Tabu-dong road, and turned northeast on it toward the town eight milesaway. This road presented a picture of devastation-dead oxen, disabledT34 tanks, wrecked artillery pieces, piles of abandoned ammunition, andother military equipment and supplies littered its course. As the battalion haltedfor the night, an exploding mine injured Colonel Clainos. He refused evacuation,but the next day was evacuated on orders of the regimental commander. Thatevening the 1st Battalion, with the 3d Battalion following close behind,advanced to the vicinity of Togae-dong, four miles short of Tabu-dong.

The premature detrucking of the 3d Battalion during the day was thefinal incident that caused General Gay to replace the 7th Cavalry regimentalcommander. That evening General Gay put in command of the regiment ColonelHarris, commanding officer of the 77th Field Artillery Battalion, whichhad been in support of the regiment. Harris assumed command just beforemidnight. [49]

Colonel Harris issued orders about midnight to assembled battalion andunit commanders that the 7th Cavalry would capture Tabu-dong on the morrow,and that the element which reached the village first was to turn southto contact the 8th Cavalry Regiment and at the same time establish defensivepositions to secure the road.

The next morning, 21 September, the 1st Battalion resumed the attackand arrived at the edge of Tabu-dong at 1255. There it encountered enemyresistance, but in a pincer movement from southwest and northwest clearedthe village by 1635. An hour later the battalion moved out of Tabu-dongdown the Taegu road in attack southward toward the 8th Cavalry Regiment.

Late that afternoon, General Gay was accompanying the 1st Battalion,8th Cavalry, advancing northward toward Tabu-dong. He and Colonel Kane,the battalion commander, were standing close to a tank when a voice cameover its radio saying, "Scrappy, this is Skirmish Red, don't fire."A few minutes later a sergeant, commanding the lead platoon of C Company,7th Cavalry, came into the position and received the personal congratulationsof the division commander upon completing the encircling movement. [50]

Meanwhile, the 3d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, arrived at Tabu-dong and turnednorth to deploy its troops in defensive positions on both sides of theroad. By this time, elements of the ROK 1st Division had cut the Sangjuroad above Tabu-dong and were attacking south toward the village. The ROK12th Regiment, farthest advanced, had a roadblock eight miles to the northeastbelow Kun vi. It appeared certain that the operations of the 1st CavalryDivision and the ROK 1st Division had cut off large numbers of the N.K.3d, 13th, and 1st Divisions in the mountainsnorth of Taegu. The next day, at September, the 11th Regiment of the ROK1st Division and units of the ROK National Police captured the Walled Cityof Ka-san, and elements of the ROK 15th Regiment reached Tabu-dong fromthe north to link up with the 1st Cavalry Division. [51]

In the mountainous area of the ROK II Corps the enemy 8th Divisionwas exhausted and the 15th practically destroyed. The ROK divisionswere near exhaustion, too, but their strength was greater than the enemy'sand they began to move slowly north again. The ROK 6th Division attackedagainst the N.K. 8th Division, which it had held withoutgain for two weeks, and in a 4-day battle destroyed the division as a combatforce. According to enemy sources, the N.K. 8th Divisionsuffered about 4,000 casualties at this time. The survivors fled northtoward Yech'on in disorder. By 21 September the ROK 6th Division was advancingnorth of Uihung with little opposition. [52]

Eastward, the ROK 8th Division, once it had gathered itself togetherand begun to move northward, found little resistance because the opposingenemy 15th Division had been practically annihilated.

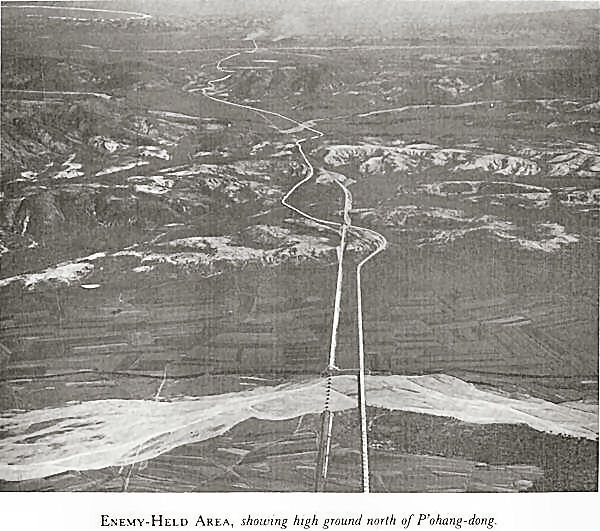

In the battle-scarred Kigye-An'gang-ni-Kyongju area of the ROK I Corpssector, units of the Capital Division fought their way through the streetsof An'gang-ni on 16 September, the day the U.N. offensive got under way.Beyond it, the ROK 3d Division had moved up to the north bank of the Hyongsan-gangjust below P'ohang-dong. The next day a battalion of the ROK 7th Division,advancing from the west, established contact with elements of the CapitalDivision and closed the 2-week-old gap between the ROK II and I Corps.

Retiring northward into the mountains, the N.K. 12th Divisionfought stubborn delaying actions and did not give up Kigye to the CapitalDivision until 22 September. It then continued its withdrawal toward Andong.This once formidable organization, originally composed largely of Koreanveterans of the Chinese Communist Army, was all but destroyed-its strengthstood at approximately 2,000 men. The North Korean and ROK divisions onthe eastern flank now resembled exhausted wrestlers, each too weak to pressagainst the other. The ROK divisions, however, had numerical superiority,better supply, daily close air support and, in the P'ohang-dong area, navalgunfire. [53]

On the 16th, naval support was particularly effective when Admiral CharlesC. Hartman's Task Group, including the battleship USS Missouri,appeared off P'ohang-dong. The big battleship pounded the enemy positionsbelow the town, along the dike north of the Hyongsan-gang, with 2,000-poundshells from its 16-inch guns. Two days later the battleship again shelledthese dike positions under observed radio fire direction by Colonel Emmerich,KMAG adviser to the ROK 3d Division. ROK troops then assaulted across thebridge, but enemy machine gunners cut them down. The number killed is unknown,but 144 were wounded in trying to cross the bridge. In a final desperatestep, thirty-one ROK soldiers volunteered to die if necessary in trying to cross the bridge.Fighter planes helped their effort by making dummy strafing passes againstthe enemy dike positions. Of the thirty-one who charged, nineteen fellon the bridge. Other ROK soldiers quickly reinforced the handful of menwho gained a foothold north of the river. There they found dead enemy machinegunners tied to their dike positions. [54]

As a preliminary move in the U.N. Offensive in the east, naval vesselson the night of 14-15 September had transported the ROK Miryang GuerrillaBattalion, specially trained and armed with Russian-type weapons, to Changsa-dong,ten miles above P'ohang-dong, where the battalion landed two and a halfhours after midnight in the rear of the N.K. 5th Division.Its mission was to harass the enemy rear while the ROK 3d Division attackedfrontally below P'ohang-dong. That evening the enemy division sent a battalionfrom its 12th Regiment to the coastal hills where the MiryangBattalion had taken a position and there engaged it. The ROK guerrillabattalion's effort turned into a complete fiasco. The U.S. Navy had torush to its assistance and place a ring of naval gunfire around it on thebeach, where enemy fire had driven the battalion. This saved it from totaldestruction. Finally, on 18 September, with great difficulty, the Navyevacuated 725 of the ROK's, 110 of them wounded, by LST. Thirty-nine deadwere left behind, as well as 32 others who refused to try to reach theevacuating ships. [55]

Although this effort to harass the enemy rear came to nothing and gavethe ROK 3d Division little help, elements of that division had combat patrolsat the edge of P'ohang-dong on the evening of 19 September. The next morningat 1015 the division captured the destroyed fishing and harbor village.One regiment drove on through the town to the high ground north of it.And in the succeeding days of 21 and 22 September the ROK 3d Division continuedstrong attacks northward, supported by naval gunfire and fighter planes,capturing Hunghae, and driving the N.K. 5th Division backon Yongdok in disorder. [56]

At the other end of the U.N. line, the left flank in the Masan area,H-hour on 16 September found the 25th Division in an embarrassing situation.Instead of being able to attack, the division was still fighting enemyforces behind its lines, and the enemy appeared stronger than ever on theheights of Battle Mountain, P'il-bong, and Sobuk-san.

General Kean and his staff felt that the division could advance alongthe roads toward Chinju only when the mountainous center of the divisionfront was clear of the enemy. The experience of Task Force Kean in early August,when the enemy had closed in behind it from the mountains, was still freshin their minds. They therefore believed that the key to the advance ofthe 25th Division lay in its center where the enemy held the heights andkept the 24th Infantry Regiment under daily attack. The 27th Infantry onthe left and the 35th Infantry on the right, astride the roads betweenChinju and Masan, could do little more than mark time until the situationin front of the 24th Infantry improved.

To carry out his plan, General Kean on 16 September organized a compositebattalion-sized task force under command of Maj. Robert L. Woolfolk, commandingofficer of the 3d Battalion, 35th Infantry, and ordered it to attack theenemy-held heights of Battle Mountain and P'il-bong the next day, withthe mission of restoring the 24th Infantry positions there. On the 17thand 18th the task force repeatedly attacked these heights, heavily supportedby artillery fire from the 8th and 90th Field Artillery Battalions andby numerous air strikes, but enemy automatic fire from the heights drove back the assaulting troops every time with heavy casualties. Withintwenty-four hours, A Company, 27th Infantry, alone suffered fifty-sevencasualties. Woolfolk's force abandoned its effort to drive the enemy fromthe peaks after its failure on the 18th, and the task group was dissolvedthe next day. [57]

During the morning of 19 September it was discovered that the enemyhad abandoned the crest of Battle Mountain during the night, and the 1stBattalion, 24th Infantry, moved up and occupied it. On the right, the 35thInfantry began moving forward. There was only light resistance until itreached the high ground in front of Chungam-ni where cleverly hidden enemysoldiers in spider holes shot at 1st Battalion soldiers from the rear.The next day the 1st Battalion captured Chungam-ni, and the 2d Battalioncaptured the long ridge line running northwest from it to the Nam River.Meanwhile, the enemy still held strongly against the division left wherethe 27th Infantry had heavy fighting in trying to move forward. [58]

On 21 September the 35th Infantry Regiment captured the well-known Notch,three miles southwest of Chungam-ni, and then swept westward eight airmiles without resistance, past the Much'on-ni road fork, to the high groundat the Chinju pass. There at 2230 the lead battalion halted for the night.At the same time, the 24th and 27th Regiments in the center and on thedivision left advanced, slowed only by the rugged terrain they had to traverse.They passed abandoned position after position from which the North Koreanspreviously had fought to the death, and saw that enemy automatic positionshad honeycombed the hills. [59]

The events of the past three days made it clear that the enemy in frontof the 25th Division in the center and on the right had started his withdrawalthe night of 18-19 September. The N.K. 7th Division withdrewfrom south of the Nam River while the 6th Division sideslippedelements to cover the entire front. Covered by the 6th Division,the 7th had crossed to the north side of the Nam River by the morningof the 19th. Then the N.K. 6th Division had withdrawn fromits positions on Sobuk-san. [60]

Although the North Korean withdrawal had been general in front of the25th Division, there were still delaying groups and stragglers in the mountains.Below Tundok on the morning of 22 September some North Koreans slippedinto the bivouac area of A Company, 24th Infantry. One platoon leader awoketo find an enemy soldier standing over him. He grabbed the enemy's bayonetand struggled with the North Korean until someone else shot the man. Nearbyanother enemy dropped a grenade into a foxhole on three sleeping men, killing two and wounding the third. A little later mortar fire fell on a companycommanders' meeting at 1st Battalion headquarters and inflicted seven casualties,including the commanding officer of Headquarters Company killed, and thebattalion executive officer, the S-1, and the S-2 wounded. [61]

Up ahead of the division advance, elements of the N.K. 6th Divisionat the Chinju pass blocked the 35th Infantry all day on 22 September, coveringthe withdrawal of the main body across the Nam River and through Chinju,six miles westward. The assault companies of the 1st Battalion, 35th Infantry,got within 200 yards of the top of Hill 152 at the pass but could go nofarther. [62]

Just before the Eighth Army breakout MacArthur had revived a much debatedproposal. On 19 September General Wright sent a message from Inch'on toGeneral Hickey, Acting Chief of Staff, FEC, in Tokyo, saying General MacArthurdirected that Plan 100-C, which provided for a landing at Kunsan, be readiedfor execution. He indicated that MacArthur wanted two U.S. divisions andone ROK division prepared to make the landing on 15 October. This proposalindicates quite clearly that on the 19th General MacArthur entertainedserious doubts about the Eighth Army's ability to break out of the PusanPerimeter. In truth it did not look very promising. General Walker, wheninformed of this plan, opposed taking any units out of the Eighth Armyline in the south. By the 22d the situation had brightened considerablyfor a breakout there, and after discussing the matter with Walker thatday General MacArthur gave up the idea of a Kunsan landing; General Hickeypenciled on the plan, "File." [63]

Aerial observers' reports on 22 September gave no clear indication ofenemy intentions. While there were reports of large enemy movements northwardthere were also large ones seen going south. Eighth Army intelligence onthat day estimated the situation to be one in which, "although theenemy is apparently falling back in all sectors, there are no indicationsof an over-all planned disengagement and withdrawal." [64] This estimateof enemy intentions was wrong. Everywhere, even though it was not yet apparentto Eighth Army, the enemy units were withdrawing, covering their withdrawalby strong blocking and delaying actions wherever possible.

In any analysis of Eighth Army's unanticipated favorable position atthis time it is imperative to calculate the effect of the Inch'on landingon the North Koreans fighting in the south. There can be little doubt thatwhen this news reached them it was demoralizing in the extreme and wasperhaps the greatest single factor in their rapid deterioration. The evidenceseems to show that news of the Inch'on landing was kept from most of theNorth Korean officers as well as nearly all the troops at the Pusan Perimeterfor nearly a week. It would appear that the North Korean High Command did not decide on a withdrawal from the Perimeter and aregrouping somewhere farther north until three or four days after the landingwhen it became evident that Seoul was in imminent danger. The pattern offighting and enemy action at the Perimeter reflects this fact.

Nowhere on 16 September, when Eighth Army began its offensive, did itscore material gains except in certain parts of the 2d Division zone wherethe 38th and 23d Infantry Regiments broke through decimated enemy forcesto reach the Naktong River. Until 19 September there was everywhere thestoutest enemy resistance and no indication of voluntary withdrawal, and,generally, U.N. advances were minor and bought only at the cost of heavyfighting and numerous casualties. Then during the night of 18-19 Septemberthe enemy 7th and 6th Divisions began withdrawingin the southern part of the line where the enemy forces were farthest fromNorth Korean soil. The 6th Division left behind well organizedand effective delaying parties to cover the withdrawals.

On 19 September Waegwan fell to the U.S. 5th Regimental Combat Team,and the ROK 1st Division in the mountains north of Taegu penetrated topoints behind the enemy 1st and 13th Divisions' lines.These divisions then started their withdrawals. The next day the ROK 3dDivision on the east coast recaptured P'ohang-dong and in the ensuing daysthe 5th Division troops in front of it fell back rapidlynorthward on Yongdok. And at the same time the ROK Army made sweeping advancesin the mountains throughout the eastern half of the front. The 1st CavalryDivision was unable to make significant gains until 20 and 21 September.On the 21st it finally recaptured Tabu-dong. West of the Naktong the U.S.2d Division fought stubborn enemy delaying forces on 21 and 22 September.

The effect of the Inch'on landing and the battles around Seoul on enemyaction at the Pusan Perimeter from 19 September onward was clearly apparent.By that date the North Korean High Command began to withdraw its main forcescommitted in the south and start them moving northward. By 23 Septemberthis North Korean retrograde movement was in full swing everywhere aroundthe Perimeter. This in itself is proof of the theater-wide military effectivenessof the Inch'on landing. The Inch'on landing will stand as MacArthur's masterpiece.

By 23 September the enemy cordon around the Pusan Perimeter was no more-Eighth Army's general attack combined with the effect of the Inch'on landing had rent it asunder. The Eighth Army and the ROK Army stood on the eve of pursuit and exploitation, a long-awaited revenge for the bitter weeks of defeat and death.

[1] Interv, author with Lt Col Paul F. Smith, 7 Oct 52 Ltr, Maj Gen Leven C. Allen to author, 10 Jan 54; Brig Gen Edwin K. Wright, FEC, Memo for Record, 4 Sep 50; Interv, author with Stebbins (EUSAK G-4 Sep 50), 4 Dec 53: Interv, author with Maj Gen George L. Eberle, 12 Jan 54.

[2] EUSAK Opn Plan 10, 6 Sep 50, and Revision, 11 Sep 50; EUSAK WD, G-3 Plans Sec, 7 Sep 50; Ibid., 15-16 Sep 50; I Corps WD, G-3 Sec, 2 Aug-30 Sep 50.

[3] I Corps WD, Hist Narr, 2 Aug-30 Sep 50; EUSAK WD, Aug 50 Summ.

[4] IX Corps WD, Hist Narr, 23-30 Sep 50. It is interesting to note that I and IX Corps had been deactivated in Japan only a few months before, in the early part of 1950, in line with maintaining the framework of four divisions and remaining within reduced army personnel ceilings.

[5] Landrum, Notes for author, recd 8 Mar 54; EUSAK Special Ord 49, 11 Sep 50; EUSAK WD, G-3 Sec, 13 and 16 Sep 50; I Corps WD, G-3 Sec, 12-19 Sep 50; EUSAK POR 195, 15 Sep 50; 24th Div WD, 15-16 Sep 50. The 3d Battalion of the 19th Regiment, 24th Division, remained at Samnangjin on the lower Naktong as a left flank guard force.

[6] IX Corps WD, Hist Summ, 23-30 Sep 50; EUSAK WD, POR 217, 22 Sep 50 (POR erroneously dated 2000O1). [7] Landrum, Notes for author, recd 8 Mar 54.

[8] EUSAK WD, 16 Sep 50, app. 1 to an. A (Intel) to Opn Plan 10 (as of 10 Sep 50).

[9] ATIS Interrog Rpts. Issue 9 (N.K. Forces), Rpt 1468, pp. 158ff, Col Lee Hak Ku; Ibid., Issue 7, Rpt 1253, p. 112, Sr Lt Lee Kwan Hyon; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 3 (N.K. 15 Div), p. 44; Ibid., Issue 96 (N.K. 5th Div), pp. 43-44; Ibid., Issue 99 (N.K. 7th Div), p. 38; Ibid., Issue 4 (N.K. 105th Armored Div), p. 39; Ibid., Issue 100 (N.K. 9th Div), p. 52: ATIS Interrog Rpts, Issue 22 (N.K. Forces), p. 4; EUSAK WD, 30 Sep 50, G-2 Sec, interrog of Maj Lee Yon Gun, Asst Regt CO, 45th Regt, 15th Div.

[10] 35th Inf WD, PW Interrog Team Rpt by Lt Herada, 151500 Sep 50.

[11] U.N. forces had captured and interned at the Eighth Army enclosure 3,380 N.K. prisoners by 15 September. The ROK Army had captured 2,254 of them; Eighth Army, 1,126. See EUSAK WD Incl 16, Provost Marshal Rpt, 15 Sep 50.

[12] GHQ FEC Sitrep, 16 Sep 50; GHQ FEC G-3 Opn Rpt, 16 Sep 50. U.S. Air Force strength in Korea was 4,726 men. The total U.N. supported strength in Korea was 221,469 men, of which about 120,000 were in the ROK Army, 83,000 assigned, and 30,000-odd in training. See EUSAK POR 65, G-4 Sec, 15 Sep 50. NAVFE strength was 52,011 men.

[13] Battle Casualties of the Army, 31 May 52, DA TAGO.

[14] Lt. Gen. Chung Il Kwon commanded the ROK Army. The six ROK divisions were the following: 1st Division-11th, 12th, 15th Regiments; 3d Division-22d, 23d, 26th Regiments; 6th Division-2d, 7th, 19th Regiments; 7th Division-3d, 5th, 8th Regiments; 8th Division-10th, 16th, 21st Regiments; and Capital Division-1st, 17th, 18th Regiments. See EUSAK WD, Br for CG, 12 Sep 50.

[15] EUSAK WD, Arty Rpt, 11 Sep 50.

[16] EUSAK POR 198, 16 Sep 50; I Corps WD, 16 Sep 50; 2d Inf WD, Sep 50; 38th Inf WD, 16 Sep 50.

[17] Maj Gen Paul L. Freeman, Jr., MS review comments, 30 Oct 57: Highlights of the Combat Activities of the 23d Inf Regt from 5 Aug 50 to 30 Sep 50; 23d Inf WD, Narr Summ, Sep 50; Ibid., G-3 Jnl, entry 151, 160207 Sep 50. Task Force Haynes, which had defended the Changnyong area since 1 September, was dissolved on 15 September.

[18] 2d Div WD, G-3 Sec, Sep 50; 23d Inf WD, Narr Summ, Sep 50; Ibid., G-3 Jnl, entry 151, 160207 Sep 50; EUSAK PIR 66, 16 Sep 50; 38th Inf Comd Rpt, Sep-Oct 50; FEAF Opns Hist, vol. I, 25 Jun-31 Oct 50, p. 168; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 94 (N.K. 2d Div), p. 38; ATIS Interrog Rpts, Issue 7 (N.K. Forces), Rpts 1208, 1233, 1242, pp. 19, 69, 82 and 131. The senior medical officer of the 17th Regiment, captured on the 17th, estimated that each of the three regiments of the 2d Division had only approximately 700 men left. See EUSAK WD, 21 Sep 50, ADVATIS Interrog Rpt of Sr Lt Lee Kwan Hyon.

[19] FEAF Opns Hist, vol. I, 25 Jun-31 Oct 50, p. 170; "Air War in Korea," Air University Quarterly Review IV, (Spring, 1951), No. 3, 70; 23d Inf Comd Rpt, Jnl entry 175, 17 Sep 50, and Pers Rpt 13, 17 Sep 50; 38th Inf Comd Rpt, Sep-Oct 50, p. 8; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 106 (N.K. Arty), p. 51; Fonecon, Allen with Hickey, GHQ FEC CofS, 17 Sep 50; EUSAK WD, G-3 Air, 17 Sep 50.

[20] Interv, author with Peploe, 12 Aug 51; 2d Div POR 132, 18 Sep 50; 2d Div WD, 18 Sep 50 and CofS Log entries 121 and 124, 18 Sep 50; 38th Inf Comd Rpt. Sep-Oct 50, pp. 9-10; 2d Div WD, G-3 Jnl, Msg 74, 181625 Sep 50; EUSAK WD, 18 Sep 50 and G-3 Jnl, Msg 181745: 2d Div WD, G-2 Jnl, entry 2107, 181525 Sep 50, and PIR 25, 18 Sep 50.

[21] 2d Div POR 132, 18 Sep 50; 2d Div WD, G-3 Sec, 18 Sep 50; 2d Div PIR 24, 17 Dec 50; see Capt. Russell A. Gugeler, Small Unit Actions in Korea, ch. V, "Patrol Crossing of the Naktong, I&R Platoon, 23d Infantry, 18 September 1950," gives details of this incident. MS in OCMH. For an account of a typical rear area action, see Capt. Edward C. Williamson, Attack of the 38th Ordnance Medical Maintenance Company by a Guerrilla Band, 20 September 1950. MS in OCMH.

[22} 24th Div WD, G-1 Hist Rpt, 26 Aug-28 Sep 50; 1st Cav Div WD, 14-16 Sep 50. The earliest 5th RCT document found in the official records is the Personnel Report for 17 September and is included in the 24th Division records.

[23] 5th RCT WD, 18 Sep 50.

[24] 5th RCT WD, 19 Sep 50; Ibid., Unit Rpt 38, 19 Sep 50; 24th Div Opn Instr 44, 17 Sep 50; 24th Div WD, G-1 Sec, 19 Sep 50; Throckmorton, MS review comments, recd 16 Apr 54.

[25] 24th Div WD, 19 Sep 50; 5th RCT WD, 19 Sep 50 and Unit Rpt 38, 19 Sep 50; EUSAK PIR 69, 19 Sep 50; ATIS Interrog Rpts, Issue 13 (N.K. Forces) Rpt 1880, p. 189. MSgt Son Tok Hui, 105th Armored Division.

[26] 5th RCT WD, 20-21 Sep 50; EUSAK WD, Br for CG, 20 Sep 50; Throckmorton, MS review comments, recd 16 Apr 54.

[27] EUSAK WD, Sep 50 Summ, p. 30; "Air War in Korea," Air University Quarterly Review, IV, No. IV (Fall, 1950), 19-39

[28] 24th Div WD, 17 Sep 50 and an. B, overlay accompanying 24th Div Opn Instr 44, 17 Sep 50.

[29] 24th Div WD, 18-19 Sep 50; 21st Inf WD, 18-19 Sep 50, and Summ, 26 Aug-28 Sep 50; Throckmorton, MS review comments, recd 16 Apr 54; Col Emerson C. Itschner, "The Naktong Crossings in Korea," The Military Engineer, XLIII, No. 292 (March-April, 1951), 96ff; Interv, author with Alkire (21st Inf) 1 Aug 51.

[30] 24th Div WD, 19 Sep 50; 21st Inf Unit Rpts 73-74, 18-20 Sep 50; 3d Engr C Bn WD, Narr Summ, Sep 50.

[31] 24th Div WD, 19 Sep 50; 3d Engr C Bn WD. Narr Summ, Sep 50.

[32] 21st Inf Unit Rpts, 19-20 Sep 50; Ltr, Gay to author, 30 Sep 53; 2d Bn, 7th Cav Jnl, 20 Sep 50; 24th Div WD, 21-22 Sep 50; EUSAK WD, 22 Sep 50; 11th Inf WD, 19-21 Sep 50 and Summ, 19-21 Sep; Maj. Gen. B. A. Coad, "The Land Campaign in Korea," op. cit., p. 4; Eric Linklater, Our Men in Korea, The Commonwealth Part in the Campaign, First Official Account (London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1952), p. 18.

[33] 24th Div WD, 21-22 Sep 50; 61st FA Bn WD, 20 Sep 50; I Corps WD, Engr Sec, 22 Sep 50; 3d Engr C Bn WD, Narr Summ, Sep 50; Itschner, "The Naktong River Crossings in Korea," op. cit.

[34] 24th Div WD, 20-22 Sep 50; 5th RCT WD, 21 Sep 50; EUSAK WD, G-3 Air, 22 Sep 50; GHQ FEC Sitrep, 22 Sep 50; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 4 (105th Armored Div), pp. 39-40; Ibid., Issue 14 (N.K. Forces), p. 4, Rpt 1901, Lt Lee Kim Chun.

[35] 23d Inf Comd Rpt. Narr, Sep 50, p. 12; Ibid., Jnl entry 183, 19 Sep 50, and entries 192 and 197, 20 Sep 50; 2d Div WD, G-3 Sec, Sep-Oct 50, p. 18 and PIR 27, 20 Sep 50; EUSAK WD POR 206, 19 Sep 50; Freeman, MS review comments, 30 Oct 57: Combat Activities of the 23d Infantry.

[36] 23d Inf WD, entries 199-202, 20 Sep 50; EUSAK WD, G-3 Sec, 20 Sep 50; Glasgow, Platoon Leader in Korea, pp. 207-24.

[37] Interv, author with Radow (M Co, 23d Inf, Sep 50), 16 Aug 50; 23d Inf WD, entries 206-10, 20 Sep 50.

[38] 23d Inf WD, 20-22 Sep 50, entries 206-210, 214-222, and 226; 23d Inf POR 26, 20-21 Sep 50; and an. I, Overlay; Glasgow, Platoon Leader in Korea, pp. 234-62. Glasgow, a platoon leader in B Company and critically wounded in the fight, indicates that part of the company behaved poorly in the enemy dawn attack.

[39] 38th Inf Comd Rpt, Sep-Oct 50, pp. 10-12; 2d Div PIR 18, 21 Sep 50; 2d Div WD, G-3 Sec, Sep-Oct 50, p. 20; Ibid., G-4 Sec; EUSAK WD, G-3 Jnl, entry 1456, 22 Sep 50. An enemy sketch captured on the 21st near Ch'ogye showed accurately every position the 1st Battalion, 38th Infantry, had occupied east of the Naktong.

[40] Ltr, Gay to author, 30 Sep 53; 2d Bn, 7th Cav, Unit Jnl, 16 Sep 50.