|

|

CHAPTER XXVIIIPursuit and Exploitation |

The Foundation of Freedom is the Courage of Ordinary PeopleHistory |

| Once the enemy has taken flight, they can be chased with no better weaponsthan air-filled bladders . . . attack, push, and pursue without cease.All maneuvers are good then; it is only precautions that are worthless. |

| MARSHAL MAURICE DE SAXE, Reveries on the Art of War |

By 23 September the North Korean Army was everywhere in retreat fromthe Pusan Perimeter. Eighth Army, motorized and led by armored spearheads,was ready to sweep forward along the main axes of advance.

The Eighth Army decision to launch the pursuit phase of the breakoutoperation came suddenly. On 20 September General Allen, in a telephoneconversation with General Hickey in Tokyo, reported, "We have nothad any definite break yet. They [the North Koreans] are softening butstill no definite indication of any break which we could turn into a pursuit."[1] The next day General Allen thought the break had come, and on 22 SeptemberGeneral Walker issued his order for the pursuit.

The Eighth Army order stated:

Enemy resistance has deteriorated along the Eighth Army front permittingthe assumption of a general offensive from present positions. In view ofthis situation it is mandatory that all efforts be directed toward thedestruction of the enemy by effecting deep penetrations, fully exploitingenemy weaknesses, and through the conduct of enveloping or encircling maneuverget astride enemy lines of withdrawal to cut his attempted retreat anddestroy him. [2]

The order directed a full-scale offensive: I Corps to continue to makethe main effort along the Taegu-Kumch'on-Taejon-Suwon axis and to effecta juncture with X Corps; the 2d Infantry Division to launch an unlimitedobjective attack along the Hyopch'on-Koch'ang-Anui-Chonju-Kanggyong axis;the 25th Division on the army's southern flank to seize Chinju and be readyto attack west or northwest on army order; and the ROK Army in the eastto destroy the enemy in its zone by deep penetrations and enveloping maneuvers.An important section of the Eighth Army order and a key to the contemplatedoperation stated, "Commanders will advance where necessary withoutregard to lateral security."

Later in the day, Eighth Army issued radio orders making IX Corps, underGeneral Coulter, operational at 1400, 23 September, and attaching the U.S. 2d and 25th Infantry Divisions toit. This order charged IX Corps with the responsibility of carrying outthe missions previously assigned to the 2d and 25th Divisions. In preparingfor the pursuit, Eighth Army moved its headquarters from Pusan back toTaegu, reopening there at 1400, 23 September. [3]

The U.N. forces around the Pusan Perimeter at this time numbered almost160,000 men, of whom more than 76,000 were in Eighth Army and about 75,000in the ROK Army. United Nations reinforcements had begun arriving in Koreaby this time. On 19 September the Philippine 10th Infantry Battalion CombatTeam began unloading at Pusan, and on 22 September the 65th RegimentalCombat Team started unloading there, its principal unit being the 65thPuerto Rican Infantry Regiment. The next day Swedish Red Cross Field Hospitalpersonnel arrived at Pusan. On the 19th, the Far East Command deactivatedthe Pusan Logistical Command and reconstituted it as the 2d LogisticalCommand-its mission of logistical support unchanged. [4]

Since pursuit of the enemy along any one of the several corridors leadingaway from the Pusan Perimeter did not materially affect that in any other,except perhaps in the case of the Taejon and Poun-Ch'ongju central roadways,the pursuit phase of the breakout operation will be described by majorcorridors of advance. The story will move from south to north and northeastaround the Perimeter. It must be remembered that the various movementswere going on simultaneously all around the Perimeter.

On the day he assumed command of operational IX Corps, 23 September,General Coulter in a meeting with General Walker at the 25th Division commandpost requested authority to change the division's axis of attack from southwestto west and northwest. He thought this would permit better co-ordinationwith the 2d Division to the north. Walker told Coulter he could alter thedivision boundaries within IX Corps so long as he did not change the corpsboundaries. [5]

The change chiefly concerned the 27th Regiment which now had to movefrom the 25th Division's south flank to its north flank. General Kean formeda special task force under Capt. Charles J. Torman, commanding officerof the 25th Reconnaissance Company, which moved through the 27th Infantryon the southern coastal road at Paedun-ni the evening of the 23d. The 27thRegiment then began its move from that place to the division's north flankat Chungam-ni. The 27th Infantry was to establish a bridgehead across theNam River and attack through Uiryong to Chinju. [6] (Map VIII)

On the morning of 24 September Task Force Torman attacked along the coastal road toward Chinju. North ofSach'on the task force engaged and dispersed about 200 enemy soldiers ofthe 3d Battalion, 104th Security Regiment.By evening it had seized the high ground at the road juncture three milessouth of Chinju. The next morning the task force moved up to the Nam Riverbridge which crossed into Chinju. In doing so one of the tanks hit a mineand fragments from the explosion seriously wounded Captain Torman, whohad to be evacuated. [7]

Meanwhile, on the main inland road to Chinju the N.K. 6th Divisiondelayed the 35th Infantry at the Chinju pass until the evening of 23 September,when enemy covering units withdrew. The next day the 35th Infantry consolidatedits position at the pass. That night a patrol reported that enemy demolitionshad rendered the highway bridge over the Nam at Chinju unusable.

On the strength of this information the 35th Regiment made plans tocross the Nam downstream from the bridge. Under cover of darkness at 0200,25 September, the 2d Battalion crossed the river two and a half miles southeastof Chinju. It then attacked and seized Chinju, supported by tank fire fromTask Force Torman across the river. About 300 enemy troops, using mortaland artillery fire, served as a delaying force in defending the town. The3d and 1st Battalions crossed the river into Chinju in the afternoon, andthat evening Task Force Torman crossed on an underwater sandbag ford thatthe 65th Engineer Combat Battalion built 200 yards east of the damagedhighway bridge. Working all night, the engineers repaired the highway bridgeso that vehicular traffic began crossing it at noon the next day, 26 September.[8]

Sixteen air miles downstream from Chinju, near the blown bridges leadingto Uiryong, engineer troops and more than 1,000 Korean refugees workedall day on the 25th constructing a sandbag ford across the Nam River. Enemymortars fired sporadically on the workers until silenced by counterbatteryfire of the 8th Field Artillery Battalion. Before dawn of the 26th the1st Battalion, 27th Infantry, crossed the Nam. Once on the north bank,elements of the regiment attacked toward Uiryong, three miles to the northwest,and secured the town just before noon after overcoming an enemy force thatdefended it with small arms and mortar fire. The regiment pressed on toChinju against negligible resistance on 28 September. [9]

On 24 September Eighth Army had altered its earlier operational orderand directed IX Corps to execute unlimited objective attacks to seize Chonjuand Kanggyong. To carry out his part of the order, General Kean organizedtwo main task forces with armored support centered about the 24th and 35thInfantry Regiments. The leading elements of these two task forces wereknown respectively as Task Force Matthews and Task Force Dolvin. Both forceswere to start their drives from Chinju. Task Force Matthews, the left-hand column, was to proceed west toward Hadong andthere turn northwest to Kurye, Namwon, Sunch'ang, Kumje, Iri, and Kunsanon the Kum River estuary. Taking off at the same time, Task Force Dolvin,the right-hand column, was to drive north out of Chinju toward Hamyang,there turn west to Namwon, and proceed northwest to Chonju, Iri, and Kanggyongon the Kum River. [10]

Three blown bridges west of Chinju delayed the departure of Task ForceMatthews (formerly Task Force Torman) until 1000, 27 September. Capt. CharlesM. Matthews, commanding officer of A Company, 79th Tank Battalion, replacedTorman in command of the latter's task force after Torman had been woundedand evacuated. He led the advance out of Chinju with the 25th ReconnaissanceCompany and A Company, 79th Tank Battalion. The 3d Battalion, 24th Infantry,followed Task Force Matthews, and the rest of the regiment came behindit. Matthews reached Hadong at 1730. [11]

In a sense, the advance of Task Force Matthews became a chase to rescuea group of U.S. prisoners that the North Koreans moved just ahead of thepursuers. Korean civilians and bypassed enemy soldiers kept telling ofthem being four hours ahead, two hours ahead-but always ahead. At Hadongthe column learned that some of the prisoners were only thirty minutesahead. From Hadong, in bright moonlight, the attack turned northwest towardKurye. About ten miles above Hadong at the little village of Komdu theadvanced elements of the task force liberated eleven American prisoners.They had belonged to the 3d Battalion, 29th Infantry Regiment. Most ofthem were unable to walk and some had open wounds. [12]

Just short of Namwon about noon the next day, 28 September, severalvehicles at the head of the task force became stuck in the river crossingbelow the town after Sgt. Raymond N. Reifers in the lead tank of the 25thReconnaissance Company had crossed ahead of them. While the rest of thecolumn halted behind the stuck vehicles Reifers continued on into Namwon.

Entering the town, Reifers found it full of enemy soldiers. Apparentlythe North Koreans' attention had been centered on two F-84 jet planes thatcould be seen sweeping in wide circles, rocketing and strafing the town,and they were unaware that pursuing ground elements were so close. Surprisedby the sudden appearance of the American tank, the North Koreans in wilddisorder jumped over fences, scurried across roof tops, and dashed madlyup and down the streets.

Reifers said later that the scene would have appeared ludicrous if hisown plight had not been so precarious. Suddenly he heard American voicescalling out, "Don't shoot! Americans! GI's here!" A second latera gateway leading into a large courtyard burst open and the prisoners-shouting,laughing, and crying-poured out into the street.

Back at the head of the stuck column, 1st Lt. Robert K. Sawyer overhis tank radio heard Reifer's voice calling out, "Somebody get uphere! I'm all alone in this town! It is full of enemy soldiers and thereare American prisoners here." Some of the tanks and vehicles now pushedahead across the stream. When Sawyer's tank turned into the main streethe saw ahead of him, gathered about vehicles, "a large group of bearded,haggard Americans. Most were bare-footed and in tatters, and all were obviouslyhalf starved. We had caught up with the American prisoners," he said,"there were eighty-six of them." [13]

Task Forces Matthews and Blair cleared Namwon of enemy soldiers. Inmidafternoon Task Force Dolvin arrived there from the east. Task ForceMatthews remained overnight in Namwon, but Task Force Blair continued ontoward Chongup, which was secured at noon the next day, 29 September. Thatevening Blair's force secured Iri. There, with the bridge across the riverdestroyed, Blair stopped for the night and Task Force Matthews joined it.Kunsan, the port city on the Kum River estuary, fell to the 1st Battalion,24th Infantry, without opposition at 1300, 30 September. [14]

Eastward of and generally parallel to the course of Task Force Matthewsand the 24th Infantry, Task Force Dolvin and the 35th Infantry moved aroundthe eastern and northern sides of the all but impenetrable Chiri-san area,just as the 24th Infantry had passed around its southern and western sides.This almost trackless waste of 750 square miles of 6,000 to 7,000-foot-highforested mountains forms a rough rectangle northwest of Chinju about thirtyby twenty-five miles in dimension, with Chinju, Hadong, Namwon, and Hamyangat its four corners. This inaccessible area had long been a hideout forCommunist agents and guerrillas in South Korea. Now, as the North Koreanforces retreated from southwest Korea, many enemy stragglers and some organizedunits with as many as 200 to 400 men went into the Chiri Mountain fastnesses.There they planned to carry on guerrilla activities. [15]

Lt. Col. Welborn G. Dolvin, commanding officer of the 88th Tank Battalion,led Task Force Dolvin out of Chinju at 0600, 26 September, on the roadnorthwest toward Hamyang, the retreat route taken by the main body of theN.K. 6th Division. The tank-infantry task force includedas its main elements A and B Companies, 89th Medium Tank Battalion, andB and C Companies, 35th Infantry. It had two teams, A and B, each formedof an infantry company and a tank company. The infantry rode the rear decksof the tanks. The tank company commanders commanded the teams. [16]

Three miles out of Chinju the lead M26 tank struck a mine. While thecolumn waited, engineers removed eleven more from the road. Half a milefarther on, a second tank was damaged in another mine field. Still fartheralong the road a third mine field, covered by an enemy platoon, stoppedthe column again. After the task force dispersed the enemy soldiers andcleared the road of mines, it found 6 antitank guns, 9 vehicles, and anestimated 7 truckloads of ammunition in the vicinity abandoned by the enemy.At dusk, the enemy blew a bridge three miles north of Hajon-ni just halfan hour before the task force reached it. During the night the task forceconstructed a bypass. [17]

The next morning, 27 September, a mine explosion damaged and stoppedthe lead tank. Enemy mortar and small arms fire from the ridges near theroad struck the advanced tank-infantry team. Tank fire cleared the leftside of the road, but an infantry attack on the right failed. The columnhalted, and radioed for an air strike. Sixteen F-51 fighter-bombers camein strafing and striking the enemy-held high ground with napalm, fragmentationbombs, and rockets. General Kean, who had come forward, watched the strikeand then ordered the task force to press the attack and break through theenemy positions. The task force broke through on the road, bypassing anestimated 600 enemy soldiers. Another blown bridge halted the column forthe night while engineers constructed a bypass.

Continuing its advance at first tight on the 28th, Task Force Dolvinan hour before noon met elements of the 23d Infantry, U.S. 2d Division,advancing from the east, at the road junction just east of Hamyang. Thereit halted three hours while engineers and 280 Korean laborers constructeda bypass around another blown bridge. Ever since leaving Chinju, Task ForceDolvin had encountered mine fields and blown bridges, the principal delayingefforts of the retreating N.K. 6th Division.

When it was approaching Hamyang the task force received a liaison planereport that enemy forces were preparing to blow a bridge in the town. OnColonel Dolvin's orders the lead tanks sped ahead, machine-gunned enemytroops who were placing demolition charges, and seized the bridge intact.This success upset the enemy's delaying plans. The rest of the afternoonthe task force dashed ahead at a speed of twenty miles an hour. It caught up with numerous enemy groups, killing some of thesoldiers, capturing others, and dispersing the rest. At midafternoon TaskForce Dolvin entered Namwon to find that Task Force Matthews and elementsof the 24th Infantry were already there.

Refueling in Namwon, Task Force Dolvin just after midnight continuednorthward and in the morning reached Chonju, already occupied by elementsof the 38th Infantry Regiment, and continued on through Iri to the KumRiver. The next day at 1500, 30 September, its mission accomplished, TaskForce Dolvin was dissolved. It had captured or destroyed 16 antitank guns,19 vehicles, 65 tons of ammunition, 250 mines, captured 750 enemy soldiers,and killed an estimated 350 more. It lost 3 tanks disabled by mines and1 officer and 45 enlisted men were wounded in action. [18]

In crossing southwest Korea from Chinju to the Kum River, Task ForceMatthews had traveled 220 miles and Task Force Dolvin, 138 miles. In thewake of Task Force Dolvin the 27th Regiment moved north from Chinju toHamyang and Namwon on 29 September and maintained security on the supplyroad. This same day, 29 September, ROK marines captured Yosu on the southcoast.

Opposite the old Naktong Bulge area, the N.K. 9th, 4th,and 2d Divisions retreated westward. At Sinban-ni the 4thDivision turned toward Hyopch'on. The 9th withdrew on Hyopch'on,and the 2d, after passing through Ch'ogye, continued on to the sameplace. Apparently the 9th Division, in the lead, had passedthrough Hyopch'on before elements of the U.S. 2d Division closed in onthe place. [19]

On 23 September the 38th Infantry of the U.S. 2d Division had hard fightingin the hills around Ch'ogye before overcoming enemy delaying forces. Thenext day the 23d Infantry from the southeast and the 38th Infantry fromthe northeast closed on Hyopch'on in a double envelopment movement. Elementsof the 38th Infantry established a roadblock on the north-south Chinju-Kumch'onroad running northeast out of Hyopch'on and cut off an estimated two enemybattalions still in the town. During the day the 3d Battalion, 23d Infantry,entered Hyopch'on after a rapid advance of eight miles from the southeast.As the North Koreans fled Hyopch'on in the afternoon, 38th Infantry firekilled an estimated 300 of them at the regiment's roadblock northeast ofthe town. Two flights of F-51 fighter planes caught the rest in the openand continued their destruction. The surviving remnant fled in utter disorderfor the hills. The country around Hyopch'on was alive with hard-pressed,fleeing North Koreans on 24 September, and the Air Force, flying fifty-threesorties in the area, wrought havoc among them. That night elements of the1st Battalion, 38th Infantry, entered Hyopch'on from the north. [20]

At daylight on the 25th, the 38th Infantry started northwest from Hyopch'onfor Koch'ang. The road soon became impassable for vehicles and the menhad to detruck and press forward on foot.

In retreating ahead of the 38th Infantry on 25 September the N.K. 2dDivision, according to prisoners, abandoned all its remaining vehiclesand heavy equipment between Hyopch'on and Koch'ang. This apparently wastrue, for in its advance from Hyopch'on to Koch'ang the 38th Infantry captured17 trucks, 10 motorcycles, 14 antitank guns, 4 artillery pieces, 9 mortars,more than 300 tons of ammunition, and 450 enemy soldiers, and killed anestimated 260 more. Division remnants, numbering no more than 2,500 men,together with their commander, Maj. Gen. Choe Hyon, who was ill, scatteredinto the mountains.

Up ahead of the ground troops, the Air Force in the late afternoon bombed,napalmed, rocketed, and strafed Koch'ang, leaving it virtually destroyed.After advancing approximately thirty miles during the day, the 38th Infantrystopped at 2030 that night only a few miles from the town. [21]

Elements of the 38th Infantry entered Koch'ang at 0830 the next morning,26 September, capturing there a North Korean field hospital containingforty-five enemy wounded. Prisoners disclosed that elements of the N.K.2d, 4th, 8th, and 10th Divisions wereto have assembled at Koch'ang, but the swift advance of the U.S. 2d Divisionhad frustrated the plan. [22]

The 23d Infantry was supposed to parallel the 38th Infantry on a roadto the south, in the pursuit to Koch'ang, but aerial and road reconnaissancedisclosed that this road was either impassable or did not exist. GeneralKeiser then directed Colonel Freeman to take a road to the north of the38th Infantry. Mounted on organic transportation, the regiment, less its1st Battalion, started at 1600 on the 25th and made a night advance toKoch'ang, fighting three skirmishes and rebuilding four small bridges onthe way. It arrived at Koch'ang soon after the 38th Infantry, in daylighton 26 September.

That evening the 23d Infantry continued the advance to Anui, fourteenmiles away, which it reached at 1930 without enemy opposition. Except forthe small town itself, the area was a maze of flooded paddies. The regimentalvehicles could find no place to move off the roads except into the villagestreets where they were dispersed as well as possible. At least one enemygroup remained in the vicinity of Anui. At 0400 the next morning, 27 September,a heavy enemy artillery and mortar barrage struck in the town. The secondround hit the 3d Battalion command post, killing the battalion executive officer,the S-2, the assistant S-3, the motor officer, the artillery liaison officer,and an antiaircraft officer. Lt. Col. R. G. Sherrard, the battalion commander,was severely wounded; also wounded were twenty-five enlisted men of theRegimental and Headquarters Companies. [23]

At least passing notice should be taken of another event on 27 September.The last organized unit of the North Korean forces east of the NaktongRiver, elements of the N.K. 10th Division, withdrew fromnotorious Hill 409 near Hyongp'ung and crossed to the west side of theriver before daylight. Patrols of the 9th Infantry Regiment entered Hyongp'ungin the afternoon, and two companies of the 2d Battalion occupied Hill 409without opposition. On 28 September the 2d Battalion, 9th Infantry, crossedthe Naktong to join the 2d Division after the newly arrived 65th RegimentalCombat Team of the U.S. 3d Division relieved it on Hill 409. [24]

At 0400, 28 September, Colonel Peploe started the 38th Infantry, withthe 2d Battalion leading, from Koch'ang in a motorized advance toward Chonju,an important town in the west coastal plain seventy-three miles away acrossthe mountains. The 25th Division also was approaching Chonju through Namwon.Meeting only light and scattered resistance, the 2d Battalion, 38th Infantry,entered Chonju at 1315, having covered the seventy-three miles in nineand a half hours. At Chonju the battalion had to overcome about 300 enemysoldiers of the 102d and 104th Security Regiments,killing about 100 of them and taking 170 prisoners.

There the 38th Infantry ran out of fuel for its vehicles. Fortunately,a 2d Division liaison plane flew over the town and the pilot learned thesituation. He reported it to the 2d Division and IX Corps which rushedgasoline forward. At 1530 on 29 September, after refueling, the 3d Battaliondeparted Chonju for Nonsan and continued to Kanggyong on the Kum River,arriving there without incident at 0300 the morning of 30 September.

The IX Corps had only two and a half truck companies with which to transportsupplies to the 25th and 2d Divisions in their long penetrations, and thedistance of front-line units from the railhead increased hourly. When the2d Division reached Nonsan on the 29th the supply line ran back more than200 road miles, much of it over mountainous terrain and often on one-wayroads, to the railhead at Miryang. The average time for one trip was forty-eighthours. In one 105-hour period, Quartermaster truck drivers supporting the2d Division got only about thirteen hours' sleep. [25]

At the end of September the 2d Division was scattered from the Kum Riversouthward, with the 38th Infantry in the Chonju-Kanggyong area, the 23d Infantry in the Anui area, and the9th Infantry in the Koryong-Samga area.

On the right flank of the U.S. 2d Division, the British 27th InfantryBrigade, attached to the U.S. 24th Division for the pursuit, was to moveagainst Songju while the 24th Division simultaneously attacked parallelto and north of it on the main highway toward Kumch'on. After passing throughSongju, the British brigade was to strike the main highway halfway betweenthe Naktong River and Kumch'on. Its path took it along the main retreatroute of the N.K. 10th Division. The brigade was across theNaktong and ready to attack before daylight on 22 September.

At dawn the 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, seized a small hill,called by the men Plum Pudding Hill, on the right of the road three milesshort of Songju. The battalion then attacked the higher ground immediatelyto the northeast, known to the British as Point 325 or Middlesex Hill.Supported by American tank fire and their own mortar and machine gun fire,the Middlesex Battalion took the hill from dug-in enemy soldiers beforedark. [26]

While the Middlesex Battalion attacked Hill 325, the Scottish HighlanderArgyll Battalion moved up to attack neighboring Hill 282 on the left ofthe road. Starting before dawn on 23 September, B and C Companies afteran hour's climb seized the crest of Hill 282 surprising there a North Koreanforce at breakfast. Across a saddle, and nearly a mile away to the southwest,higher Hill 388 dominated the one they had just occupied. C Company startedtoward it.

But enemy troops occupying this hill already were moving to attack theone just taken by the British. The North Koreans supported their attackwith artillery and mortar fire, which began falling on the British. Theaction continued throughout the morning with enemy fire increasing in intensity.Shortly before noon, with American artillery fire inexplicably withdrawnand the five supporting U.S. tanks unable to bring the enemy under firebecause of terrain obstacles, the Argylls called for an air strike on enemy-heldHill 388. [27]

Just after noon the Argylls heard the sound of approaching planes. ThreeF-51 Mustangs circled Hill 282 where the British displayed their whiterecognition panels. The enemy on Hill 388 also displayed white panels.To his dismay, Captain Radcliff of the tactical air control party was unableto establish radio contact with the flight of F-51's. Suddenly, at 1215,the Mustangs attacked the wrong hill; they came in napalming and machine-gunningthe Argyll position.

The terrible tragedy was over in two minutes and left the hilltop asea of orange flame. Survivors plunged fifty feet down the slope to escapethe burning napalm. Maj. Kenneth Muir, second in command of the Argylls, who had led an ammunition resupply and litter-bearingparty to the crest before noon, watching the flames on the crest die down,noticed that a few wounded men still held a small area on top. Acting quickly,he assembled about thirty men and led them back up the hill before approachingNorth Koreans reached the top. There, two bursts of enemy automatic firemortally wounded him as he and Maj. A. I. Gordon-Ingram, B Company commander,fired a 2-inch mortar. Muir's last words as he was carried from the hilltopwere that the enemy "will never get the Argylls off this ridge."But the situation was hopeless. Gordon-Ingram counted only ten men withhim able to fight, and some of them were wounded. His three Bren guns werenearly out of ammunition. At 1500 the survivors were down at the foot ofthe hill.

The next day a count showed 2 officers and 11 men killed, 4 officersand 70 men wounded, and 2 men missing for a total of 89 casualties; ofthis number, the mistaken air attack caused approximately 60. [28]

That night, after the Argyll tragedy, the 1st Battalion, 19th Infantry,attacked south from Pusang-dong on the Waegwan-Kumch'on highway and capturedSongju at 0200, 24 September. From there it moved to link up with the British27th Brigade below the town. That day and the next the 19th Infantry andthe British brigade mopped up in the Songju area. On the afternoon of 25September the British brigade, released from attachment to the U.S. 24thDivision, reverted to I Corps control.

The N.K. 10th Division which had been fighting in theSongju area, its ammunition nearly gone and its vehicles out of fuel, withdrewon the 24th and 25th after burying its artillery. A captured division surgeonestimated the 10th Division had about 25 percent of its originalstrength at this time. The N.K. I Corps, about 25 September,ordered all its units south of Waegwan to retreat northward. [29]

On 23 September, the day that disaster struck the British from the airnear Songju, the U.S. 24th Division started its attack northwest alongthe Taejon-Seoul highway. General Church had echeloned his three regimentsin depth so that a fresh regiment would take the lead at short intervalsand thus maintain impetus in the attack. Leading off for the division,the 21st Infantry headed for Kumch'on, the N.K. headquarters. Elementsof the N.K. 105th Armored Division blocked the waywith dug-in camouflaged tanks, antitank guns, and extensive mine fields.

In the afternoon a tank battle developed in which D Company, 6th MediumTank Battalion (Patton M46), lost four tanks to enemy tank and antitankfire. During a slow advance, American tanks and air strikes in turn destroyedthree enemy tanks. [30]

Just as this main Eighth Army drive started it was threatened with asupply breakdown. Accurate enemy artillery fire during the night of the22d destroyed the only raft at the Naktong River ferry and cut the footbridgethree times. The ferrying of vehicles and supplies during the day practicallystopped, but at night local Koreans carried across the river the suppliesand ammunition needed the next day.

Shortly after midnight, 23-24 September, the 5th Regimental Combat Teampassed through the 21st Infantry to take the lead. Enemy troops in positionson Hill 140, north of the highway, stopped the regiment about three mileseast of Kumch'on. There the North Koreans fought a major delaying actionto permit large numbers of their retreating units to escape. The NorthKorean command diverted its 9th Division, retreating fromthe lower Naktong toward Taejon, to Kumch'on to block the rapid EighthArmy advance. Remaining tanks of two regiments of the N.K. 105th Armored Division and the 849thIndependent Anti-Tank Regiment, the latter recentlyarrived at Kumch'on from the north, also joined in the defense of the town.

In the battle that followed in front of Kumch'on, the 24th Divisionlost 6 Patton tanks to enemy mines and antitank fire, while the North Koreanslost 8 tanks, 5 to air attack and 3 to ground fire. In this action theenemy 849th Regiment was practically destroyed. The 5th RegimentalCombat Team and supporting units lost approximately 100 men killed or wounded,most of them to tank and mortar fire. Smaller actions flared simultaneouslyat several points on the road back to Waegwan as bypassed enemy units struckat elements of the 19th Infantry bringing up the rear of the 24th Divisionadvance. [31]

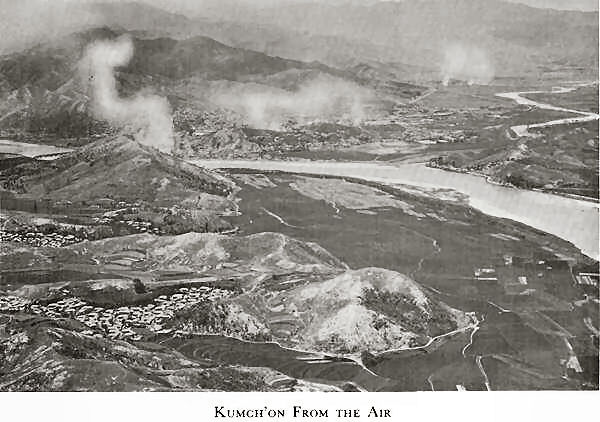

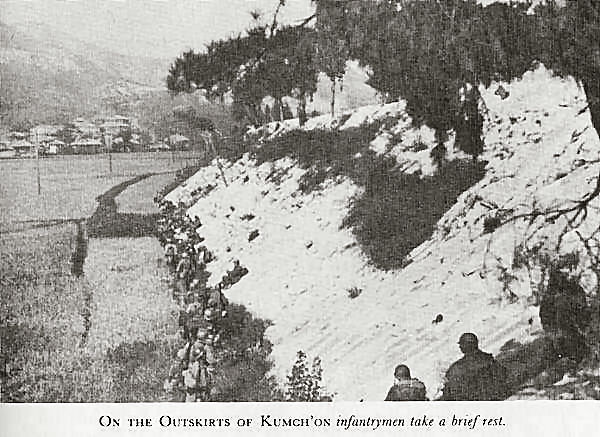

As a result of the battle in front of Kumch'on on 24 September, the21st Infantry swung to the north of the highway and joined the 5th RegimentalCombat Team that night in a pincer attack on the town. The 3d Battalionof the 5th Regimental Combat Team entered Kumch'on the next morning, andby 1445 that afternoon the town, a mass of rubble from bombing and artillerybarrages, was cleared of the enemy.

That evening the 21st Infantry continued the attack westward. The 24thDivision was interested only in the highway. If it was clear, the columnwent ahead. With the fall of Kumch'on on the 25th, enemy resistance meltedaway and it was clear that the North Koreans were intent only on escaping.[32]

On 26 September the 19th Infantry took the division lead and its 2dBattalion entered Yongdong without resistance. In the town jail the troopsfound and liberated three American prisoners. The regiment continued onand reached Okch'on, ten miles east of Taejon, at 0200, 27 September. Thereit halted briefly to refuel the tanks and give the men a little rest.

At 0530 the regiment resumed the advance-but not for long. Just outsideOkch'on the lead tank hit a mine and enemy antitank fire then destroyedit. The 1st Battalion deployed and attacked astride the road but advancedonly a short distance. The North Koreans held the heights west of Okch'onin force and, as at Kumch'on three days earlier, were intent on a majordelaying operation. This time it was to permit thousands of their retreatingfellow soldiers to escape from Taejon. An American tank gunner moving upto join the fight in front of Taejon sang, "The last time I saw Taejon,it was not bright or gay. Today I'm going to Taejon and blow the placeaway." [33]

This fight in front of Taejon on 27 September disclosed that the city,as expected, was an assembly point for retreating North Korean units southand west of Waegwan. The 300 prisoners taken during the day included menfrom seven North Korean divisions. The reports of enemy tanks destroyedin the Taejon area during the day are confusing, conflicting, and, takentogether, certainly exaggerated. The ground forces reported destroying13 tanks on the approaches to the city, 3 of them by A Company, 19th Infantry,bazooka teams. The Air Force claimed a total of 20 tanks destroyed duringthe day, 13 of them in the Taejon area, and another 8 damaged. [34]

On the morning of the 28th an air strike at 0700 hit the enemy blocking;position. When the 2d Battalion advanced cautiously up the slopes, it wasunopposed. It then became clear that the North Koreans had withdrawn duringthe night. Aerial reconnaissance at the time of the air strike disclosedapproximately 800 North Korean troops moving out of Taejon on the roadpast the airstrip. At noon aerial observers saw more enemy troops assemblingat the railroad station and another concentration of them a few miles westof Taejon turning toward Choch'iwon. The Air Force napalmed and strafedstill another force of 1,000 enemy soldiers west of the city.

Scouts of the 2d Battalion, 19th Infantry, and engineers of C Company,3d Engineer Combat Battalion, entered the outskirts of Taejon at 1630.An hour later the 19th Infantry secured the city after engineers had cleared mines ahead of tanks leading the main column.At 1800 a 24th Division artillery liaison plane landed at the Taejon airstrip.[35]

On 28 September, the day it entered Taejon, the 19th Infantry capturedso many North Korean stragglers that it was unable to keep an accuratecount of them. The capture of large numbers of prisoners continued duringthe last two days of the month; on the 30th the 24th Division took 447of them. At Taejon the division captured much enemy equipment, includingfour U.S. howitzers lost earlier and fifty new North Korean heavy machineguns still packed in cosmoline. At Choch'iwon the North Koreans were destroyingequipment to prevent its capture. [36] Already other U.S. forces had passedTaejon and Choch'iwon on the east to cut the main highway farther northat Ch'onan and Osan.

With the capture of Taejon, the 24th Division accomplished its missionin the pursuit. And sweet revenge it was for the Taro Leaf Division tore-enter this now half-destroyed town where it had suffered a disastrousdefeat nine weeks earlier. Fittingly enough, it was the 19th Infantry Regimentand engineers of the 3d Engineer Combat Battalion, among the last to leavethe burning city on that earlier occasion, who led the way back in. Butthere was bitterness too, for within the city American troops soon discoveredthat the North Koreans had perpetrated there one of the greatest mass killingsof the entire Korean War. American soldiers were among the victims.

While this is not the place to tell in detail the story of the NorthKorean atrocities perpetrated on South Korean civilians and soldiers andsome captured American soldiers, an account of the breakout and pursuitwould not be complete without at least a brief description of the grislyevidence that came to light at that time. Everywhere the advancing columnsfound evidence of atrocities as the North Koreans hurried to liquidatepolitical and military prisoners held in jails before they themselves retreatedin the face of the U.N. advance. At Sach'on the North Koreans burned thejail, causing some 280 South Korean police, government officials, and landownersheld in it to perish. At Anui, at Mokp'o, at Kongju, at Hamyang, at Chonju,mass burial trenches containing the bodies of hundreds of victims, includingsome women and children, were found, and near the Taejon airstrip the bodiesof about 500 ROK soldiers, hands tied behind backs, lay in evidence ofmass killing and burial.

Between 28 September and 4 October a frightful series of killings andburials were uncovered in and around the city. Several thousand South Koreancivilians, estimated to number between 5,000 and 7,000, 17 ROK Army soldiers,and at least 40 American soldiers had been killed. After Taejon fell tothe North Koreans on 20 July civilian prisoners had been packed into theTaejon city jail and still others into the Catholic Mission. Beginningon 23 September, after the first U.S. troops had crossed the Naktong, theNorth Koreans began executing these people. They were taken out in groups of 100 and 200, bound to each other and hands tiedbehind them, led to previously dug trenches, and shot. By 26 SeptemberAmerican forces had approached so close to Taejon that the N.K. SecurityPolice knew they had to hurry. The executions were speeded up and the lastof them took place just before the city fell.

Of the thousands of victims only six survived-two American soldiers,one ROK soldier, and three South Korean civilians. Wounded and feigningdeath, they had been buried alive. The two wounded Americans had only athin layer of loose soil over them, enabling them to breathe sufficientlyto stay alive until they could punch holes to the surface, one of themwith a lead pencil. Still wired to their dead comrades beneath the soiland partially buried themselves, they were rescued when the city fell tothe 24th Division. Hundreds of American soldiers, including General Milburn,the I Corps commander, and General Church, the 24th Division commander,saw these ghastly burial trenches and the pathetic bodies of the victims.[37]

On 29 September the 24th Division command post moved to Taejon. Fromthere the division had the task of protecting the army line of communicationsback to the Naktong River. Its units were strung out for nearly 100 miles:the 9th Infantry held the Taejon area up to the Kum River, the 21st Infantryextended from Taejon southeast to Yongdong, the 5th Regimental Combat Teamwas in the Kumch'on area, and the 24th Reconnaissance Company secured theWaegwan bridges.

The Eighth Army breakout plans initially required the 1st Cavalry Divisionto cross the Naktong River at Waegwan and follow the 24th Division towardKumch'on and Taejon. As the breakout action progressed, however, I Corpschanged the plan so that the 1st Cavalry Division would cross the riverat some point above Waegwan, pursue a course east of and generally parallelto that of the 24th Division, and seize Sangju. General Milburn left toGeneral Gay the decision as to where he would cross. General Gay, the 1stCavalry Division commander, and others, including Colonel Holmes, his chiefof staff, and Colonel Holley of the 8th Engineer Combat Battalion, hadproposed a crossing at Naktong-ni where a North Korean underwater bridgewas known to exist. General Walker rejected this proposal. He himself flewin a light plane along the Naktong above Waegwan and selected the ferrysite at Sonsan as the place the division should cross. [38]

In front of the 1st Cavalry Division two enemy divisions were retreating on Sangju. The N.K. 3d Divisionreportedly had only 1,800 men when its survivors arrived there. The otherdivision, the 13th, was in complete disorder in the vicinity ofTabu-dong and northward along the road to Sangju when the 1st Cavalry Divisionprepared to engage in the pursuit. [39]

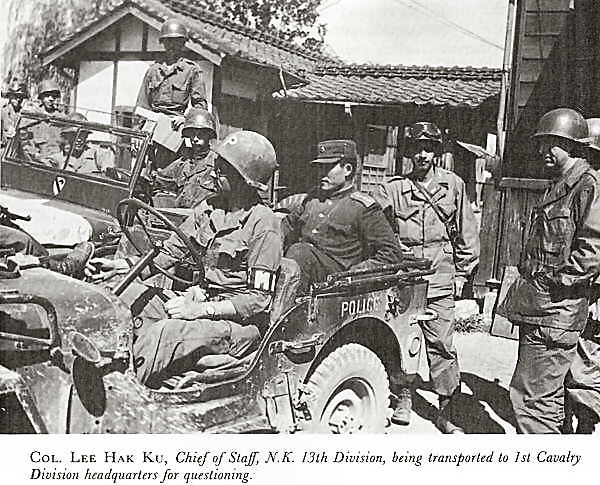

Shortly before noon, 21 September, General Walker telephoned from Taeguto General Hickey in Tokyo. He had important news-the chief of staff ofthe N.K. 13th Division had surrendered that morning. Walkertold Hickey that, based on the prisoner's testimony, the N.K. IICorps had ordered its divisions on 17 September to go on the defensiveand that the 13th Division knew nothing of the Inch'on landing.[40]

The 13th Division's chief of staff had indeed surrenderedthat morning. Shortly after daylight Sr. Col. Lee Hak Ku gently shook twosleeping American soldiers of the 8th Cavalry Regiment on the roadsidenear the village of Samsan-dong, four miles south of Tabu-dong. Once theywere awake, the 30-year-old North Korean surrendered to them.

Colonel Lee had slipped away from his companions during the night andapproached the American lines alone. He was the ranking North Korean prisonerat the time and remained so throughout the war. Before he became chiefof staff of the 13th Division, Lee had been operations officer(G-3) of the N.K. II Corps. Later he was to become notoriousas the leader of the Communist prisoners of the Compound 76 riots on KojeIsland in 1952.

Now, however, on the day of his voluntary surrender, Colonel Lee wasmost co-operative. He gave a full report on the deployment of the 13thDivision troops in the vicinity of Tabu-dong, the location of thedivision command post and the remaining artillery, the status of supply,and the morale of the troops. He gave the strength of the division on 21September as approximately 1,500 men. The division, he said, was no longeran effective fighting unit, it held no line, and its survivors were fleeingfrom the Tabu-dong area toward Sangju. The regiments had lost communicationwith the division and each, acting on its own impulse and according tonecessity, was dispersed in confusion. Many other 13th Divisionprisoners captured subsequently confirmed the situation described by ColonelLee.

Colonel Lee said the 19th Regiment had about 200 men,the 21st Regiment about 330, the 23d about 300; that from70 to 80 percent of the troops were South Korean conscripts and this conditionhad existed for a month; that the officers and noncommissioned officerswere North Korean; that all tanks attached to the division had been destroyedand only 2 of 16 self-propelled guns remained; that there were still 9122-mm. howitzers and 5 120-mm. mortars operational; that only 30 out of300 trucks remained; that rations were down one-half; and that supply cameby rail from Ch'orwon via Seoul to Andong. [41]

At the time of Colonel Lee's surrender, General Gay had already directedLt. Col. William A. Harris, Commanding Officer, 7th Cavalry Regiment, tolead the pursuit movement for the 1st Cavalry Division. Colonel Harris,now with a 2-battalion regiment (the 2d Battalion had relieved the British27th Brigade on the Naktong), organized Task Force 777 for the effort.Each digit of the number represented one of the three principal elementsof the force: the 7th Cavalry Regiment, the 77th Field Artillery Battalion,and the 70th Tank Battalion. Harris assigned Lt. Col. James H. Lynch's3d Battalion as the lead unit, and this force in turn was called Task ForceLynch. In addition to the 3d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, it included B Company,8th Engineer Combat Battalion; two platoons of C Company, 70th Tank Battalion(7 M4 tanks); the 77th Field Artillery Battalion (less one battery); the 3d Platoon, Heavy MortarCompany; the regimental I&R Platoon; and a tactical air control party.[42]

After helping to repel an attack by a large force of North Koreans cutoff below Tabu-dong and seeking to escape northward, Task Force Lynch startedto move at 0800, 22 September from a point just west of Tabu-dong. Brushingaside small scattered enemy groups, Colonel Lynch put tanks in the leadand the column moved forward. Up ahead flights of planes coursed up anddown the road attacking fleeing groups of enemy soldiers.

Near Naksong-dong, where the road curved over the crest of a hill, enemyantitank fire suddenly hit and stopped the lead tank. No one could seethe enemy guns. General Gay, who was with the column, sent the remainingfour tanks in the advance group over the crest of the hill at full speedfiring all weapons. In this dash they overran two enemy antitank guns.Farther along, the column halted while men in the point eliminated a groupof North Koreans in a culvert in a 10-minute grenade battle. [43]

After the task force had turned into the river road at the village ofKumgok but was still short of its initial objective, the Sonsan ferry,a liaison plane flew over and dropped a message ordering it to continuenorth to Naktong-ni for the river crossing. The column reached the Sonsanferry at 1545. There, before he turned back to the division command postin Taegu, General Gay approved Lynch's decision to stop pending confirmationof the order not to cross the river there but to proceed to Naktong-ni.At 1800 Lynch received confirmation and repetition of the order, and anhour later he led his task force onto the road, heading north for Naktong-ni,ten miles away.

A bright three-quarter moon lit the way as the task force hastened forward.Five miles up the river road it began to pass through burning villages,and then suddenly it came upon the rear elements of retreating North Koreanswho surrendered without resistance.

An hour and a half before midnight the lead tanks halted on the bluffoverlooking the Naktong River crossing at Naktong-ni. Peering ahead, menin the lead tank saw an antitank gun and fired on it. The round strucka concealed enemy ammunition truck. Shells in the truck exploded and agreat conflagration burst forth. The illumination caused by the chancehit lighted the surrounding area and revealed a fascinating and eerie sight.Abandoned enemy tanks, trucks, and other vehicles littered the scene, whilebelow at the underwater bridge several hundred enemy soldiers were in thewater trying to escape across the river. The armor and other elements ofthe task force fired into them, killing an estimated 200 in the water.[44]

Task Force Lynch captured a large amount of enemy equipment at the Naktong-ni crossing site, including2 abandoned and operable T34 tanks; 50 trucks, some of them still carryingU.S. division markings; and approximately 10 artillery pieces. Accordingto prisoners taken at the time, this enemy force consisted principallyof units of the N.K. 3d Division, but it included also some menfrom the 1st and 13th Divisions.

Reconnaissance parties reported the ford crossable in waist-deep waterand the far bank free of enemy troops. Colonel Lynch then ordered the infantryto cross to the north bank. At 0430, 23 September, I and K Companies steppedinto the cold water of the Naktong and began wading the river. The crossingcontinued to the accompaniment of an exploding enemy ammunition dump atthe other end of the underwater bridge. At 0530 the two companies securedthe far bank. Altogether, in the twenty-two hours since leaving Tabu-dong,Task Force Lynch had advanced thirty-six miles, captured 5 tanks, 50 trucks,6 motorcycles, 50 artillery pieces, secured a Naktong River crossing site,and had killed or captured an estimated 500 enemy soldiers. [45]

During the 23d, Maj. William O. Witherspoon, Jr., led his 1st Battalionacross the river and continued on ten miles northwest to Sangju, whichhe found abandoned by the enemy. Meanwhile, Engineer troops put into operationat Naktong-ni a ferry and raft capable of transporting trucks and tanksacross the river, and on the 24th they employed 400 Korean laborers toimprove the old North Korean underwater bridge. Tanks were across the riverbefore noon that day and immediately moved forward to join the task forceat Sangju.

As soon as the tanks arrived, Colonel Harris sent Capt. John R. Flynnwith K Company, 7th Cavalry, and a platoon of tanks thirty miles fartherup the road to Poun, which they entered before dark. Colonel Harris hadauthority only to concentrate the regiment at Poun; he was not to go anyfarther.

On the 24th also, General Gay sent a tank-infantry team down the roadfrom Sangju toward. Kumch'on where the 24th Division was engaged in a hardfight on the main Waegwan-Taejon-Seoul highway. Since this took the forceoutside the 1st Cavalry Division zone of action, I Corps ordered it towithdraw, although it had succeeded in contacting elements of the 24thDivision. [46]

On 24-25 September General Gay concentrated the 1st Cavalry Divisionin the Sangju-Naktong-ni area while his advanced regiment, the 7th Cavalry,stayed at Poun. About dark on the 25th he received a radio message fromI Corps forbidding him to advance his division farther. Gay wanted to protestthis message but was unable to establish radio communication with the corps.He was able, however, to send a message to Eighth Army headquarters byliaison plane asking for clarification of what he thought was a confusion of General Walker's orders, and requesting authorityto continue the breakthrough and join X Corps in the vicinity of Suwon.During the evening, field telephone lines were installed at Gay's forwardechelon division headquarters at the crossing site, and there, just beforemidnight, General Gay received a telephone call from Col. Edgar T. Conley,Jr., Eighth Army G-1, who said General Walker had granted authority forhim to go all the way to the link-up with X Corps if he could do so. [47]

Acting quickly on this authority, General Gay called a commanders' conferencein a Sangju schoolhouse the next morning, 26 September, and issued oralorders that at twelve noon the division would start moving day and nightuntil it joined the X Corps near Suwon. The 7th Cavalry Regiment was tolead the advance by way of Poun, Ch'ongju, Ch'onan, and Osan. Divisionheadquarters and the artillery would follow. The 8th Cavalry Regiment wasto move on Ansong via Koesan. At noon the 5th Cavalry Regiment, to be relievedby elements of the ROK 1st Division, was to break off its attack towardHamch'ang and form the division rear guard; upon reaching Choch'iwon andCh'onan it was to halt, block enemy movement from the south and west, andawait further orders. [48]

On the right of the 1st Cavalry Division the ROK 1st Division, as partof the U.S. I Corps and the only ROK unit operating as a part of EighthArmy, had passed through Tabu-dong from the north on 22 September and headedfor the Sonsan ferry of the Naktong. It crossed the river there on the25th, and moved north on the army right flank to relieve elements of the1st Cavalry Division, and particularly the 5th Cavalry Regiment, in theHamch'ang-Poun area above Sangju. The 1st Cavalry Division was now freeto employ all its units in the pursuit. [49]

Upon receiving General Gay's orders at the commanders' conference inSangju, Colonel Harris in turn ordered Colonel Lynch at Poun to lead northwestwith his task force as rapidly as possible to effect a juncture with 7thDivision troops of the X Corps somewhere in the vicinity of Suwon. Thistask force was the same as in the movement from Tabu-dong on the 22d, exceptthat now the artillery contingent comprised only C Battery of the 77thField Artillery Battalion.

The regimental I&R Platoon and 1st Lt. Robert W. Baker's 3d Platoonof tanks, 70th Tank Battalion, led Task Force Lynch out of Poun at 1130,26 September. Baker had orders from Lynch to move at maximum tank speedand not to fire unless fired upon. For mile after mile they encounteredno enemy opposition-only cheers from South Korean villagers watching thecolumn go past. Baker found Ch'ongju deserted except for a few civilianswhen he entered it at midafternoon.

Approximately at 1800, after traveling sixty-four miles, Baker's tanksran out of gasoline and the advance stopped at Ipchang-ni. For some reason the refuel truck had not joined the tank-ledcolumn. Three of the six tanks refueled from gasoline cans collected inthe column.

Just after these three tanks had refueled, members of the I&R Platoonon security post down the road ran up and said a North Korean tank wasapproaching. Instead, it proved to be three North Korean trucks which approachedquite close in the near dark before their drivers realized that they hadcome upon an American column. The drivers immediately abandoned their vehicles,and one of the trucks crashed into an I&R jeep. On the trucks was enoughgasoline to refuel the other three tanks. About 2000 the column was atlast ready to proceed. [50]

Colonel Harris ordered Colonel Lynch, at the latter's discretion, todrive on in the gathering darkness with vehicular lights on. This timeBaker's platoon of tanks, rather than the I&R Platoon, was to leadthe column. The other platoon of three tanks was to bring up the rear.At his request, Colonel Lynch gave Baker authority to shoot at North Koreansoldiers if he thought it necessary. Shortly after resuming the advanceat 2030 the task force entered the main Seoul highway just south of Ch'onan.

It soon became apparent that the task force was catching up with enemysoldiers. Ch'onan was full of them. Not knowing which way to turn at astreet intersection, Baker stopped, pointed, and asked a North Korean soldieron guard, "Osan?" He received a nod just as the soldier recognizedhim as an American and began to run away. The rest of the task force followedthrough Ch'onan without opposition. Groups of enemy soldiers just stoodaround and watched the column go through. Beyond Ch'onan, Baker's tankscaught up with an estimated company of enemy soldiers marching north andfired on them with tank machine guns. Frequently they passed enemy vehicleson the road, enemy soldiers on guard at bridges, and other small groups.

Soon the three lead tanks began to outdistance the rest of the column,and Colonel Lynch was unable to reach them by radio to slow them. In thissituation, he formed a second point with a platoon of infantry and a 3.5-inchbazooka team riding trucks, the first truck carrying a .50-caliber ring-mountedmachine gun. Actions against small enemy groups began to flare and increasein number. When they were ten miles south of Osan men in the task forceheard from up ahead the sound of tank and artillery fire. Lynch orderedthe column to turn off its lights. [51]

Separated from the rest of Task Force Lynch, and several miles in frontof it by now, Baker's three tanks rumbled into Osan at full speed. Afterpassing through the town, Baker stopped just north of it and thought hecould hear vehicles of the task force on the road behind him, althoughhe knew he was out of radio communication with it. T34 tank tracks in theroad indicated that enemy armor might be near.

Starting up again, Baker encountered enemy fire about three or fourmiles north of Osan. His tanks ran through it and then Baker saw AmericanM26 tank tracks. At this point fire against his tanks increased. Antitankfire sheared off the mount of the .50-caliber machine gun on the thirdtank and decapitated one of its crew members. Baker's tanks, now approachingthe lines of the U.S. 31st Infantry, X Corps, were receiving American smallarms and 75-mm. recoilless rifle fire. American tanks on the line heldtheir fire because the excessive speed of the approaching tanks, the soundof their motors, and their headlights caused the tankers to doubt thatthey were enemy. One tank commander let the first of Baker's tanks go through,intending to fire on the second, when a white phosphorus grenade lit upthe white star on one of the tanks and identified them in time to avoida tragedy. Baker stopped his tanks inside the 31st Infantry lines. He hadestablished contact with elements of X Corps. The time was 2226, 26 September;the distance, 106.4 miles from the starting point at Poun at 1130 thatmorning. [52]

That Baker ever got through was a matter of great good luck for, unknownto him, he had run through a strong enemy tank force south of Osan whichapparently thought his tanks were some of its own, then through the NorthKorean lines north of Osan, and finally into the 31st Infantry positionjust beyond the enemy. Fortuitously, American antitank and antipersonnelmines on the road in front of the American position had just been removedbefore Baker's tanks arrived, because the 31st Infantry was preparing tolaunch an attack.

Baker's tanks may have escaped destruction from American weapons becauseof a warning given to X Corps. Shortly after noon of 26 September MacArthur'sheadquarters in Tokyo had radioed a message to X Corps, to NAVFE, and tothe Far East Air Forces saying that elements of Eighth Army might appearat any time in the X Corps zone of action and for the corps to take everyprecaution to prevent bombing, strafing, or firing on these troops. A littlelater, at midafternoon, Generals Walker and Partridge, flying from Taeguunannounced, landed at Suwon Airfield and conferred with members of the31st Infantry staff for about an hour. Walker said that elements of the1st Cavalry Division attacking from the south would probably arrive inthe Osan area and meet the 7th Division within thirty-six hours. [53]

After his miraculous escape, Baker and the 31st Infantry tank crewsat the front line tried unsuccessfully to reach Task Force Lynch by radio.

Instead of being right behind Baker at Osan, the rest of Task ForceLynch was at least an hour behind him. After turning out vehicular lightsapproximately ten miles south of Osan, Task Force Lynch continued in blackout.Just south of the village of Habong-ni, Colonel Lynch, about midnight,noticed a T34 tank some twenty yards off the road and commented to CaptainWebel, the regimental S-3 who accompanied the task force, that the AirForce must have destroyed it. Many men in the column saw the tank. Suddenly it opened fire with cannon and machine gun. Asecond enemy tank, unnoticed up to that time, joined in the fire. TaskForce Lynch's vehicular column immediately pulled over and the men hitthe ditch.

Lt. John G. Hill, Jr., went ahead to the point to bring back its rocketlauncher team. This bazooka team destroyed one of the T34's, but the secondone moved down the road firing into vehicles and running over several ofthem. It finally turned off the road into a rice paddy where it continuedto fire on the vehicles. A 75-mm. recoilless rifle shell immobilized thetank, but it still kept on firing. Captain Webel had followed this tankand at one point was just on the verge of climbing on it to drop a grenadedown its periscope hole when it jerked loose from a vehicle it had crashedinto and almost caught him under its tracks. Now, with the tank immobilizedin the rice paddy, a 3.5-inch bazooka team moved up to destroy it but theweapon would not fire. Webel pulled a 5-gallon can of gasoline off oneof the vehicles and hurried to the side of the tank. He climbed on it andpoured the gasoline directly on the back and into the engine hatch. A fewspurts of flame were followed by an explosion which blew Webel about twentyfeet to the rear of the tank. He landed on his side but scrambled to hisfeet and ran to the road. He had minor burns on face and hands and tworibs broken. The burning tank illuminated the entire surrounding area.

Up at the head of the halted column, Colonel Lynch heard to the norththe sound of other tank motors. He wondered if Baker's three tanks werereturning. Watching, he saw two tanks come over a hill 800 yards away.Fully aware that they might be enemy tanks, Lynch quickly ordered his driver,Cpl. Billie Howard, to place the lead truck across the road to block it.The first tank was within 100 yards of him before Howard got the truckacross the road and jumped from it. The two tanks halted a few yards awayand from the first one a voice called out in Korean, "What the hellgoes on here?" A hail of small arms fire replied to this shout.

The two tanks immediately closed hatches and opened fire with cannonand machine guns. The truck blocking the road burst into flames and burned.

The three tanks still with Task Force Lynch came up from the rear ofthe column and engaged the enemy tanks. Eight more T34's quickly arrivedand joined in the fight. The American tanks destroyed one T34, but twoof them in turn were destroyed by the North Korean tanks. Webel, in runningforward toward the erupting tank battle, came upon a group of soldierswho had a 3.5-inch bazooka and ammunition for it which they had just pulledfrom one of the smashed American trucks. No one in the group knew how tooperate it. Webel took the bazooka, got into position, and hit two tanks,immobilizing both. As enemy soldiers evacuated the tanks, he stood up andfired on them with a Thompson submachine gun.

Sgt. Willard H. Hopkins distinguished himself in this tank-infantrymelee by mounting an enemy tank and dropping grenades down an open hatch,silencing the crew. He then organized a bazooka team and led it into actionagainst other tanks. In the tank-infantry battle that raged during an houror more, this bazooka team was credited by some sources with destroying or helping to destroy 4 of the enemy tanks. Pfc. JohnR. Muhoberac was an outstanding member of this team. One of the enemy tanksran all the way through the task force position shooting up vehicles andsmashing into them as it went. At the southern end of the column a 105-mm.howitzer had been set up and there, at a point-blank range of twenty-fiveyards, it destroyed this tank. Unfortunately, heroic Sergeant Hopkins waskilled in this exchange of crossfire as he was in the act of personallyattacking this tank. Combined fire from many weapons destroyed anothertank. Of the 10 tanks in the attacking column, 7 had been destroyed. The3 remaining T34's withdrew northward. In this night battle Task Force Lynchlost 2 men killed, 38 wounded, and 2 tanks and 15 other vehicles destroyed.[54]

After the last of the enemy tanks had rumbled away to the north, ColonelHarris decided to wait for daylight before going farther. At 0700 the nextmorning, 27 September, the task force started forward again. The men wereon foot and prepared for action. Within a few minutes the point ran intoan enemy tank which a 3.5-inch bazooka team destroyed. An enemy machinegun crew opened fire on the column but was quickly overrun and the gunnerskilled in a headlong charge by Lt. William W. Woodside and two enlistedmen. A little later the column came upon two abandoned enemy tanks andblew them up. The head of Task Force Lynch reached Osan at 0800.

At 0826, 27 September, north of Osan at a small bridge, Platoon Sgt.Edward C. Mancil of L Company, 7th Cavalry, met elements of H Company,31st Infantry, 7th Division. Task Force 777 sent a message to General Gaywhich said in part, "Contact between H Company, 31st Infantry Regiment,7th Division, and forward elements of Task Force 777 established at 0826hours just north of Osan, Korea." [55]

After the link-up with elements of the 31st Infantry, elements of TaskForce 777 did not actually participate in this regiment's attack againstthe North Koreans on the hills north of Osan. Their communication equipment,including the forward air controllers, and their medical troops, however,did assist the 31st Infantry. General Gay arrived at Osan before noon and,upon seeing the battle in progress on the hills to the north, conferredwith a 31st Infantry battalion commander. He offered to use the 8th CavalryRegiment as an enveloping force and assist in destroying the enemy. Healso offered to the 31st Infantry, he said, the use of the 77th and 99thField Artillery Battalions and one tank company. The battalion commander said he would need concurrence of higher authority. Just whathappened within the 31st Infantry after General Gay made this offer hasnot been learned. But elements of the 1st Cavalry Division stood idly byat Osan while the 31st Infantry fought out the action which it did notwin until the next afternoon, 28 September. General Barr, commanding generalof the 7th Infantry Division, has said he was never informed of GeneralGay's offer of assistance. [56]

In this rapid advance to Osan, the 1st Cavalry Division cut off elementsof the 105th Armored Division in the Ansong and P'yongt'aekarea and miscellaneous units in the Taejon area. On the 28th, elementsof C Company, 70th Tank Battalion, and K Company, 7th Cavalry, with thestrong assistance of fighter-bombers, destroyed at least seven of ten T34'sin the P'yongt'aek area, five by air strikes. Elements of the 16th ReconnaissanceCompany barely escaped destruction by these enemy tanks, and did suffercasualties. [57]

As late as 29 September, L Company of the 5th Cavalry Regiment ambushedapproximately fifty enemy soldiers in nine Russian-built jeeps drivingnorth from the vicinity of Taejon.

Eastward, the ROK Army made advances from Taegu that kept pace withEighth Army, and in some instances even outdistanced it. This performanceis all the more remarkable because the ROK Army, unlike the Eighth Army,was not motorized and its soldiers moved on foot.

In the ROK II Corps, the 6th and 8th Divisions on 24 September gainedapproximately sixteen miles. The 6th Division advanced on Hamch'ang andentered it the night of 25 September. By the 27th it was advancing acrossthe roughest part of the Sobaek Range, past Mun'gyong in the high passes,on its way to Chungju. On the last day of the month the 6th Division encounteredenemy delaying groups as it approached Wonju.

The ROK 8th Division made similarly rapid advances on the right of the6th Division. Its reconnaissance elements entered Andong before midnightof the 24th. Five spans of the 31-span bridge over the Naktong there weredown. Remnants of two enemy divisions, the N.K. 12th and 8th,were retreating on and through Andong at this time. The 12th Divisionwas pretty well through the town, except for rear guard elements, whenadvanced units of the ROK 8th Division arrived, but the main body of theN.K. 8th Division had to detour into the mountains becauseROK troops arrived there ahead of it. After two days of fighting, duringwhich it encountered extensive enemy mine fields, the ROK 8th Divisionsecured Andong on 26 September. That evening the division's advanced elementsentered Yech'on, twenty miles northwest of Andong. The next day some ofits troops were at Tanyang preparing to cross the upper Han River. [58] On the last day of the month the division metstrong enemy resistance at Chech'on and bypassed the town in the race northward.

The ROK Capital Division was keeping pace with the others in the pursuit.On the 27th it had entered Ch'unyang, about thirty-one miles east of theROK 8th Division, and was continuing northward through high mountains.

On the night of 1-2 October, shortly after midnight, an organized NorthKorean force of from 1,000 to 2,000 soldiers, which had been bypassed someplace in the mountains, struck with savage fury as it broke out in itsattempt to escape northward. Directly in its path was Wonju where the ROKII Corps headquarters was then located. This force overran the corps headquartersand killed many of its men, including five American officers who were attachedto the corps or who had come to Wonju on liaison missions. The North Koreansran amok in Wonju until morning, killing an estimated 1,000 to 2,000 civilians.[59]

Along the east coast the ROK 3d Division, with heavy U.S. naval gunfiresupport, captured Yongdok on 25 September. A huge cloud of black smokehung overhead from the burning city. The fall of the town apparently caughtthe N.K. 5th Division by surprise. Some Russian-built truckswere found with motors running, and artillery pieces were still in positionwith ammunition at hand. Horse-drawn North Korean signal carts were foundwith ponies hitched and tied to trees. After the fall of Yongdok it appearsthat remnants of the 5th Division, totaling now no more thana regiment, turned inland for escape into the mountains. One North Koreanregimental commander divided his three remaining truckloads of ammunitionand food among his men and told them to split into guerrilla bands.

In the pursuit up the coastal road above Yongdok, Maj. Curtis J. Ivey,a member of KMAG, with the use of twenty-five 2 1/2-ton trucks made availablefor the purpose through the efforts of Colonel McPhail, KMAG adviser tothe ROK I Corps, led the ROK's northward in shuttle relays. When a roadblockwas encountered it was Major Ivey who usually directed the action of thepoint in reducing it. [60]

The impressive gains by the ROK units prompted General Walker to remarkon 25 September, "Too little has been said in praise of the SouthKorean Army which has performed so magnificently in helping turn this warfrom the defensive to the offensive." [61]

On up the coast road raced the ROK 3d Division. It secured Samch'okon the morning of 29 September, and then continued on toward Kangnung.It moved north as fast as feet and wheels could take it over the coastalroad. It led all ROK units, in fact, all units of the United Nations Command,in the dash northward, reaching a point only five miles below the 38thParallel on the last day of the month. [62]

The last week of September witnessed a drastic change in the patternof North Korean military activity. Enemy targets were disappearing fromthe scene. On 24 September some fighter pilots, unable to find targets,returned to their bases without having fired a shot. Survivors of the oncevictorious North Korea People's Army were in flight or in hiding, and,in either case, they were but disorganized and demoralized remnants. On1 October there occurred an incident illustrating the state of enemy demoralization.An Air Force Mosquito plane pilot dropped a note to 200 North Korean soldiersnortheast of Kunsan ordering them to lay down their arms and assemble ona nearby hill. They complied. The pilot then guided U.N. patrols to thewaiting prisoners.

The virtual collapse of the North Korean military force caused GeneralMacArthur on 1 October to order the Air Force to cease further destructionof rail, highway, bridge, and other communication facilities south of the38th Parallel, except where they were known to be actively supporting anenemy force. Air installations south of the 40th Parallel were not to beattacked, and he halted air action against strategic targets in North Korea.[63]

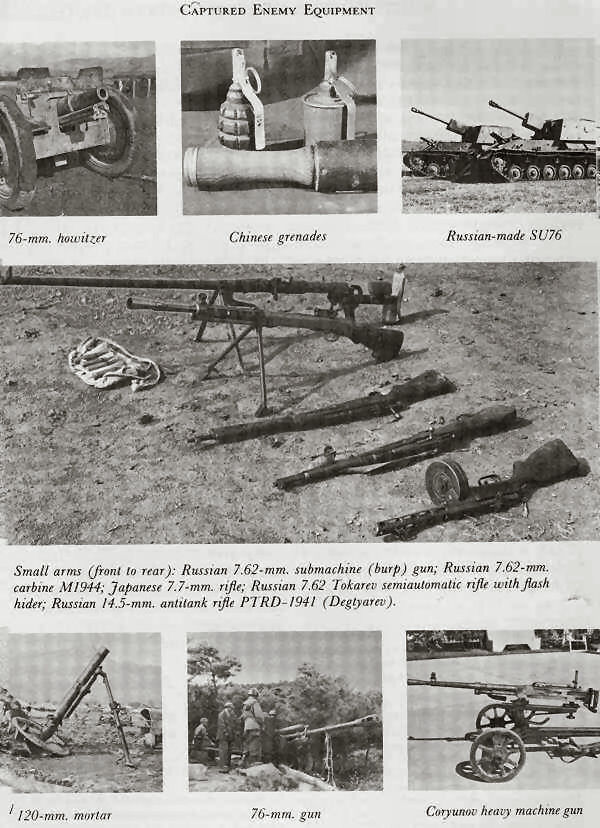

The extent of his collapse was truly a death blow to the enemy's hopesfor continuing the war with North Korean forces alone. Loss of weaponsand equipment in the retreat north from the Pusan Perimeter was of a scopeequal to or greater than that suffered by the ROK Army in the first weekof the war. For the period 23-30 September, the IX Corps alone captured4 tanks, 4 self-propelled guns, 41 artillery pieces, 22 antitank guns,42 mortars, and 483 tons of ammunition. In I Corps, the 24th Division onone day, 1 October, captured on the Kumsan road below Taejon 7 operabletanks and 15 artillery pieces together with their tractors and ammunition.On the last day of September the 5th Cavalry Regiment captured three trainscomplete with locomotives hidden in tunnels. A few miles north of Andongadvancing ROK forces found approximately 10 76-mm. guns, 8 120-mm. mortars,5 trucks, and 4 jeeps, together with dead enemy soldiers, in a tunnel-allhad been destroyed earlier by air force napalm attacks at either end ofthe tunnel. At Uisong, ROK forces captured more than 100 tons of rice,other supplies, and most of the remaining equipment of one North Koreandivision. The North Koreans had abandoned many tanks, guns, vehicles, ammunition, and other equipment becausethey lacked gasoline to operate their vehicles. [64]

During the approximately three months of the war up to the end of September,all U.N. combat arms had made various claims regarding destroyed enemyequipment, especially tanks and self-propelled guns. Air Force claims forthe period, if totaled from daily reports, would be extravagantly high.After the U.N. breakout from the Pusan Perimeter, in the period from 26September to 21 October 1950, seven survey teams traveled over all majorroutes of armored movement between the Perimeter line and the 38th Parallel,and also along the Kaesong-Sariwon-P'yongyang highway above the Parallel.This survey disclosed 239 destroyed or abandoned T34 tanks and 74 self-propelled76-mm. guns. The same survey counted 60 destroyed U.S. tanks. [65]

According to this survey, air action destroyed 102 (43 percent) of theenemy tanks, napalm accounting for 60 of them or one-fourth the total enemytank casualties; there were 59 abandoned T34's without any visible evidenceof damage, also about one-fourth the total; U.N. tank fire accounted for39 tanks (16 percent); and rocket launchers were credited with 13 tanks(5 percent). The number credited to bazooka fire is in error, for the numbercertainly is much higher. Very likely air action is credited in this surveywith many tanks that originally were knocked out with infantry bazookafire. There are many known cases where aircraft attacked immobilized tanksafter bazooka fire had stopped them. There was an almost complete absenceof enemy tanks destroyed by U.S. antitank mines.

No reliable information is available concerning the number of damagedtanks the North Koreans were able to repair and return to action. But thefigure of 239 found destroyed or abandoned comes close to being the totalnumber used by the North Korea People's Army in South Korea. Very few escapedfrom the Pusan Perimeter into North Korea at the end of September.

From July through September 1950 United States tank losses to all causeswas 136. A survey showed that mine explosions caused 70 percent of theloss. This high rate of U.S. tank casualties in Korea to mines is all themore surprising since in World War II losses to mines came to only 20 percentof tank losses in all theaters of operations. [66]

In the two weeks beginning with 16 September, the breakout and pursuitperiod, the U.N. forces in the south placed 9,294 prisoners in the EighthArmy stockade. This brought the total to 12,777, Eighth Army had captured6,740 of them and the ROK Army 6,037. Beginning with 107 prisoners on 16September the number had jumped to 435 on 23 September and passed the 1,000 mark daily with 1,084 on 27 September,1,239 the next day, and 1,948 on 1 October. [67]

The rapid sweep of the U.N. forces northward from the Pusan Perimeterin the last week of September bypassed thousands of enemy troops in themountains of South Korea. One of the largest groups, estimated to numberabout 3,000 and including soldiers from the N.K. 6th and 7thDivisions with about 500 civil officials, took refuge initiallyin the Chiri Mountains of southwest Korea. At the close of the month, ofthe two major enemy concentrations known to be still behind the U.N. lines,one was south of Kumch'on in the Hamyang area and the other northeast andnorthwest of Taejon.

Just before midnight, 1 October, a force of approximately sixty NorthKorean riflemen, using antitank and dummy mines, established and maintaineda roadblock for nearly ten hours across the main Seoul highway about fifteenmiles northwest of Kumch'on. A prisoner said this roadblock permitted about2,000 North Korean soldiers and a general officer of the N.K. 6thDivision to escape northward. The 6th at the time apparentlystill had its heavy machine guns and 82-mm. mortars but had discarded allheavier weapons in the vicinity of Sanch'ong. [68]

Enemy sources make quite clear the general condition of the North KoreanArmy at the end of September. The 6th Division started itswithdrawal in good order, but most of its surviving troops scattered intothe Chiri Mountain area and elsewhere along the escape route north so thatonly a part reached North Korea. The 7th Division commanderreportedly was killed in action near Kumch'on as the division retreatednorthward; remnants assembled in the Inje-Yanggu area above the 38th Parallelin mid-October. In the 2d Division, Maj. Gen. Choe Hyon,the division commander, had only 200 troops with him north of Poun at theend of September. Other elements of the division had scattered into thehills.

Parts of the 9th and 10th Divisions retreated throughTaejon, and other parts cut across the Taejon highway below the city inthe vicinity of Okch'on when they learned that the city had already fallen.Only a handful of men of the 105th Armored Divisionreached North Korea. The commanding general of the N.K. I Corpsapparently dissolved his headquarters at Choch'iwon during the retreatand then fled with some staff officers northeast into the mountains ofthe Taebaek Range on or about 27 September. From the central front nearTaegu, 1,000 to 1,800 men of the 3d Division succeeded in reachingP'yonggang in what became known as the Iron Triangle at the beginning ofOctober. The 1st Division, retreating through Wonju and Inje,assembled approximately 2,000 men at the end of October.

Of all the North Korean divisions fighting in South Korea perhaps noother suffered destruction as complete as the 13th. Certainly noother yielded so many high-ranking officers as prisoners of war. In August the 13thDivision artillery commander surrendered; on 21 September Col. LeeHak Ku, the chief of staff, surrendered; three days later the commanderof the self-propelled gun battalion surrendered; the division surgeon surrenderedon the 27th; and Col. Mun Che Won, a 26-year-old regimental commander,surrendered on 1 October after hiding near Tabu-dong for nearly a week.The commander of the 19th Regiment, 22-year-old Lt. Col.Yun Bon,, Hun. led a remnant of his command northward by way of Kunwi,Andong, and Tanyang. Near Tanyang, finding his way blocked by ROK troops,he marched his regiment, then numbering 167 men, into a ROK police stationat Subi-myon and surrendered. A few members of the division eventuallyreached the P'yonggang area in the Iron Triangle.

Remnants of the 8th Division, numbering perhaps 1,500men, made their way northeast of P'yonggang and continued on in Octoberto a point near the Yalu River. Some small elements of the 15thDivision escaped northward through Ch'unch'on to Kanggye in NorthKorea. From Kigye about 2,000 men of the 12th Division retreatedthrough Andong to Inje, just north of the 38th Parallel, picking up stragglersfrom other divisions on the way so that the division numbered about 3,000to 3,500 men upon arrival there. Remnants of the 5th Divisioninfiltrated northward above Yongdok along and through the east coast mountainsin the direction of Wonsan.

The bulk of the enemy troops that escaped from the Pusan Perimeter assembledin the Iron Triangle and the Hwach'on-Inje area of east-central North Koreajust above the 38th Parallel. On 2 October an Air Force pilot reportedan estimated 5,000 enemy marching in small groups along the edge of theroad north of the 38th Parallel between Hwach'on and Kumhwa.

The commanding general of the N.K. II Corps and his staffapparently escaped to the Kumhwa area in the Iron Triangle, and the bestavailable evidence indicates that the commanding general and staff of theN.K. Army Front Headquarters at Kumch'on also escapednortheast to the Iron Triangle. From there in subsequent months this headquartersdirected guerrilla operations on U.N. lines of communications.