|

|

CHAPTER IIIInvasion Across the Parallel |

The Foundation of Freedom is the Courage of Ordinary PeopleHistory |

| He, therefore, who desires peace, should prepare for war. He who aspiresto victory, should spare no pains to train his soldiers. And he who hopesfor success, should fight on principle, not chance. No one dares to offendor insult a power of known superiority in action. |

| VEGETIUS, Military Institutions of the Romans |

On 8 June 1950 the P'yongyang newspapers published a manifesto whichthe Central Committee of the United Democratic Patriotic Front had adoptedthe day before proclaiming as an objective a parliament to be elected inearly August from North and South Korea and to meet in Seoul on 15 August,the fifth anniversary of the liberation of Korea from Japanese rule. [1]It would appear from this manifesto that Premier Kim Il Sung and his Sovietadvisers expected that all of Korea would be overrun, occupied, and "elections"held in time to establish a new government of a "united" Koreain Seoul by mid-August.

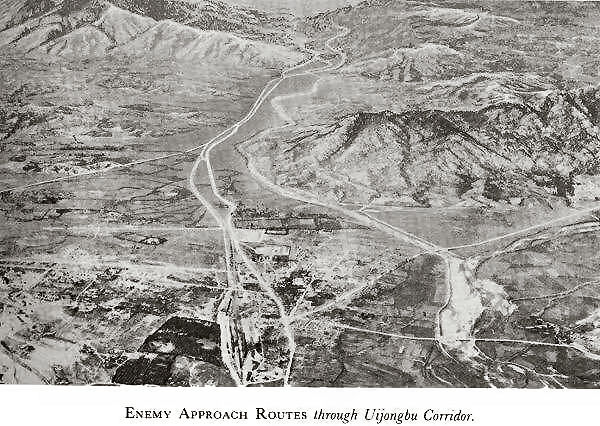

During the period 15-24 June the North Korean Command moved all RegularArmy divisions to the close vicinity of the 38th Parallel, and deployedthem along their respective planned lines of departure for the attack onSouth Korea. Some of these units came from the distant north. Altogether,approximately 80,000 men with their equipment joined those already alongthe Parallel. They succeeded in taking their positions for the assaultwithout being detected. The attack units included 7 infantry divisions,1 armored brigade, 1 separate infantry regiment, 1 motorcycle regiment,and 1 Border Constabulary brigade. This force numbered approximately 90,000men supported by 150 T34 tanks. General Chai Ung Jun commanded it. Allthe thrusts were to follow major roads. In an arc of forty miles stretchingfrom Kaesong on the west to Ch'orwon on the east the North Koreans concentratedmore than half their infantry and artillery and most of their tanks fora converging attack on Seoul. The main attack was to follow the UijongbuCorridor, an ancient invasion route leading straight south to Seoul. [2]

In preparation for the attack the chief of the NKPA Intelligence Section on 18 June issued Reconnaissance Order1, in the Russian language, to the chief of staff of the N.K. 4th Division,requiring that information of enemy defensive positions guarding theapproach to the Uijongbu Corridor be obtained and substantiated beforethe attack began. [3] Similar orders bearing the same date, modified onlyto relate to the situation on their immediate front, were sent by the sameofficer to the 1st, 2d, 3d, 6th, and 7th Divisions, the 12thMotorcycle Regiment, and the BC 3d Brigade. No doubt such ordersalso went to the 5th Division and possibly other units. [4]

On 22 Tune Maj. Gen. Lee Kwon Mu, commanding the N.K. 4th Division,issued his operation order in the Korean language for the attack downthe Uijongbu Corridor. He stated that the 1st Division on his rightand the 3d Division on his left would join in the attack leadingto Seoul. Tanks and self-propelled artillery with engineer support wereto lead it. Preparations were to be completed by midnight 23 June. Afterpenetrating the South Korean defensive positions, the division was to advanceto the Uijongbu-Seoul area. [5] Other assault units apparently receivedtheir attack orders about the same time.

The North Korean attack units had arrived at their concentration pointsgenerally on 23 June and, by 24 June, were poised at their lines of departurefor attack. Officers told their men that they were on maneuvers but mostof the latter realized by 23-24 June that it was war. [6]

Destined to bear the brunt of this impending attack were elements offour ROK divisions and a regiment stationed along the south side of theParallel in their accustomed defensive border positions. They had no knowledgeof the impending attack although they had made many predictions in thepast that there would be one. As recently as 12 June the U.N. Commissionin Korea had questioned officers of General Roberts' KMAG staff concerningwarnings the ROK Army had given of an imminent attack. A United Statesintelligence agency on 19 June had information pointing to North Koreanpreparation for an offensive, but it was not used for an estimate of thesituation. The American officers did not think an attack was imminent.If one did come, they expected the South Koreans to repel it. [7] The SouthKoreans themselves did not share this optimism, pointing to the fighterplanes, tanks, and superior artillery possessed by the North Koreans, andtheir numerically superior Army. In June 1950, before and immediately afterthe North Korean attack, several published articles based on interviewswith KMAG officers reflect the opinion held apparently by General Robertsand most of his KMAG advisers that the ROK Army would be able to meet anytest the North Korean Army might impose on it. [8]

Invasion

Scattered but heavy rains fell along the 38th Parallel in the pre-dawndarkness of Sunday, 25 June 1950. Farther south, at Seoul, the day dawnedovercast but with only light occasional showers. The summer monsoon seasonhad just begun. Rain-heavy rain-might be expected to sweep over the variouslytinted green of the rice paddies and the barren gray-brown mountain slopesof South Korea during the coming weeks.

Along the dark, rain-soaked Parallel, North Korean artillery and mortarsbroke the early morning stillness. It was about 0400. The precise momentof opening enemy fire varied perhaps as much as an hour at different pointsacross the width of the peninsula, but everywhere it signaled a co-ordinatedattack from coast to coast. The sequence of attack seemed to progress fromwest to east, with the earliest attack striking the Ongjin Peninsula atapproximately 0400. [9] (Map 1)

The blow fell unexpectedly on the South Koreans. Many of the officersand some men, as well as many of the KMAG advisers, were in Seoul and othertowns on weekend passes. [10] And even though four divisions and one regimentwere stationed near the border, only one regiment of each division andone battalion of the separate regiment were actually in the defensive positionsat the Parallel. The remainder of these organizations were in reserve positionsten to thirty miles below the Parallel. Accordingly, the onslaught of theNorth Korea People's Army struck a surprised garrison in thinly held defensivepositions.

After the North Korean attack was well under way, the P'yongyang radiobroadcast at 1100 an announcement that the North Korean Government haddeclared war against South Korea as a result of an invasion by South Koreanpuppet forces ordered by "the bandit traitor Syngman Rhee." [11]The broadcast said the North Korea People's Army had struck back in self-defenseand had begun a "righteous invasion." Syngman Rhee, it stated,would be arrested and executed. [12] Shortly after noon, at 1335, PremierKim Il Sung, of North Korea, claimed in a radio broadcast that South Koreahad rejected every North Korean proposal for peaceful unification, hadattacked North Korea that morning in the area of Haeju above the OngjinPeninsula, and would have to take the consequences of the North Korean counterattacks. [13]

The North Korean attack against the Ongjin Peninsula on the west coast,northwest of Seoul, began about 0400 with a heavy artillery and mortarbarrage and small arms fire delivered by the 14th Regiment of theN.K. 6th Division and the BC 3d Brigade. The groundattack came half an hour later across the Parallel without armored support.It struck the positions held by a battalion of the ROK 17th Regiment commandedby Col. Paik In Yup. [14]

The first message from the vicinity of the Parallel received by theAmerican Advisory Group in Seoul came by radio about 0600 from five adviserswith the ROK 17th Regiment on the Ongjin Peninsula. They reported the regimentwas under heavy attack and about to be overrun. [15] Before 0900 anothermessage came from them requesting air evacuation. Two KMAG aviators, Maj.Lloyd Swink and Lt. Frank Brown, volunteered to fly their L-5 planes fromSeoul. They succeeded in bringing the five Americans out in a single trip.[16]

The Ongjin Peninsula, cut off by water from the rest of South Korea,never had been considered defensible in case of a North Korean attack.Before the day ended, plans previously made were executed to evacuate theROK 17th Regiment. Two LST's from Inch'on joined one already offshore,and on Monday, 26 June, they evacuated Col. Paik In Yup and most of twobattalions-in all about 1,750 men. The other battalion was completely lostin the early fighting. [17]

The 14th Regiment, 6th Division, turned over the Ongjin Peninsulaarea to security forces of the BC 3d Brigade on the second day andimmediately departed by way of Haeju and Kaesong to rejoin its division.[18]

East of the Ongjin Peninsula, Kaesong, the ancient capital of Korea,lay two miles south of the Parallel on the main Seoul-P'yongyang highwayand railroad. Two battalions of the 12th Regiment, ROK 1st Division, heldpositions just north of the town. The other battalion of the regiment wasat Yonan, the center of a rich rice-growing area some twenty miles westward.The 13th Regiment held Korangp'o-ri, fifteen air miles east of Kaesongabove the Imjin River, and the river crossing below the city. The 11thRegiment, in reserve, and division headquarters were at Suisak, a smallvillage and cantonment area a few miles north of Seoul. Lt. Col. LloydH. Rockwell, senior adviser to the ROK 1st Division, and its youthful commander,Col. Paik Sun Yup, had decided some time earlier that the only defenseline the division could hold in case of attack was south of the Imjin River.[19]

Songak-san (Hill 475), a mountain shaped like a capital T with its stemrunning east-west, dominated Kaesong which lay two miles to the south of it. The 38th Parallel ran almostexactly along the crest of Songak-san, which the North Koreans had longsince seized and fortified. In Kaesong the northbound main rail line linkingSeoul-P'yongyang-Manchuria turned west for six miles and then, short ofthe Yesong River, bent north again across the Parallel.

Capt. Joseph R. Darrigo, assistant adviser to the ROK 12th Regiment,1st Division, was the only American officer on the 38th Parallel the morningof 25 June. He occupied quarters in a house at the northeast edge of Kaesong,just below Songak-san. At daybreak, approximately 0500, Captain Darrigoawoke to the sound of artillery fire. Soon shell fragments and small armsfire were hitting his house. He jumped from bed, pulled on a pair of trousers,and, with shoes and shirt in hand, ran to the stairs where he was met byhis Korean houseboy running up to awaken him. The two ran out of the house,jumped into Darrigo's jeep, and drove south into Kaesong. They encounteredno troops, but the volume of fire indicated an enemy attack. Darrigo decidedto continue south on the Munsan-ni Road to the Imjin River.

At the circle in the center of Kaesong small arms fire fell near Darrigo'sjeep. Looking off to the west, Darrigo saw a startling sight-half a mileaway, at the railroad station which was in plain view, North Korean soldierswere unloading from a train of perhaps fifteen cars. Some of these soldierswere already advancing toward the center of town. Darrigo estimated therewere from two to three battalions, perhaps a regiment, of enemy troopson the train. The North Koreans obviously had relaid during the night previouslypulled up track on their side of the Parallel and had now brought thisforce in behind the ROK's north of Kaesong while their artillery barrageand other infantry attacked frontally from Songak-san. The 13th and15th Regiments of the N.K. 6th Division delivered the attackon Kaesong.

Most of the ROK 12th Regiment troops at Kaesong and Yonan were killedor captured. Only two companies of the regiment escaped and reported tothe division headquarters the next day. Kaesong was entirely in enemy handsby 0930. Darrigo, meanwhile, sped south out of Kaesong, reached the ImjinRiver safely, and crossed over to Munsan-ni. [20]

Back in Seoul, Colonel Rockwell awakened shortly after daylight thatSunday morning to the sound of pounding on the door of his home in theAmerican compound where he was spending the weekend. Colonel Paik and afew of his staff officers were outside. They told Rockwell of the attackat the Parallel. Paik phoned his headquarters and ordered the 11th Regimentand other units to move immediately to Munsan-ni-Korangp'o-ri and occupyprearranged defensive positions. Colonel Rockwell and Colonel Paik thendrove directly to Munsan-ni. The 11th Regiment moved rapidly and in goodorder from Suisak and took position on the left of the 13th Regiment, both thereby protecting the approaches to the Imjin bridge.There they engaged in bitter fighting, the 13th Regiment particularly distinguishingitself. [21]

Upon making a reconnaissance of the situation at Munsan-ni, ColonelRockwell and Colonel Paik agreed they should blow the bridge over the ImjinRiver according to prearranged plans and Paik gave the order to destroyit after the 12th Regiment had withdrawn across it. A large body of theenemy so closely followed the regiment in its withdrawal, however, thatthis order was not executed and the bridge fell intact to the enemy. [22]

The N.K. 1st Division and supporting tanks of the 105th ArmoredBrigade made the attack in the Munsan-ni-Korangp'o-ri area. At firstsome ROK soldiers of the 13th Regiment engaged in suicide tactics, hurlingthemselves and the high explosives they carried under the tanks. Othersapproached the tanks with satchel or pole charges. Still others mountedtanks and tried desperately to open the hatches with hooks to drop grenadesinside. These men volunteered for this duty. They destroyed a few tanksbut most of them were killed, and volunteers for this duty soon becamescarce. [23]

The ROK 1st Division held its positions at Korangp'o-ri for nearly threedays and then, outflanked and threatened with being cut off by the enemydivisions in the Uijongbu Corridor, it withdrew toward the Han River.

On 28 June, American fighter planes, under orders to attack any organizedbody of troops north of the Han River, mistakenly strafed and rocketedthe ROK 1st Division, killing and wounding many soldiers. After the planesleft, Colonel Paik got some of his officers and men together and told them,"You did not think the Americans would help us. Now you know better."[24]

The main North Korean attack, meanwhile, had come down the UijongbuCorridor timed to coincide with the general attacks elsewhere. It got underway about 0530 on 25 June and was delivered by the N.K. 4th and3d Infantry Divisions and tanks of the 105th Armored Brigade.[25] This attack developed along two roads which converged at Uijongbuand from there led into Seoul. The N.K. 4th Division drove straightsouth toward Tongduch'on-ni from the 38th Parallel near Yonch'on. The N.K.3d Division came down the Kumhwa-Uijongbu-Seoul road, often calledthe P'och'on Road, which angled into Uijongbu from the northeast. The 107thTank Regiment of the 105th Armored Brigade with about fortyT34 tanks supported the 4th Division; the 109th Tank Regiment with another forty tanks supported the 3d Divisionon the P'och'on Road. [26]

The 1st Regiment of the ROK 7th Division, disposed along the Parallel,received the initial blows of the N.K. 3d and 4th Divisions.In the early fighting it lost very heavily to enemy tanks and self-propelledguns. Behind it at P'och'on on the eastern road was the 9th Regiment; behindit at Tongduch'on-ni on the western road was the 3d Regiment. At 0830 aROK officer at the front sent a radio message to the Minister of Defensein Seoul saying that the North Koreans in the vicinity of the Parallelwere delivering a heavy artillery fire and a general attack, that theyalready had seized the contested points, and that he must have immediatereinforcements-that all ROK units were engaged. [27] The strong armoredcolumns made steady gains on both roads, and people in Uijongbu, twentymiles north of Seoul, could hear the artillery fire of the two convergingcolumns before the day ended. At midmorning reports came in to Seoul that Kimpo Airfield was under air attack. A short time later,two enemy Russian-built YAK fighter planes appeared over the city and strafedits main street. In the afternoon, enemy planes again appeared over Kimpoand Seoul. [28]

Eastward across the peninsula, Ch'unch'on, like Kaesong, lay almoston the Parallel. Ch'unch'on was an important road center on the PukhanRiver and the gateway to the best communication and transport net leadingsouth through the mountains in the central part of Korea. The attacks thusfar described had been carried out by elements of the N.K. I Corps.From Ch'unch'on east ward the N.K. II Corps, with headquartersat H'wachon north of Ch'unch'on, controlled the attack formations. TheN.K. 2d Division at H'wachon moved down to the border, replacinga Border Constabulary unit, and the N.K. 7th Division did likewisesome miles farther eastward at Inje. The plan of attack was for the 2dDivision to capture Ch'unch'on by the afternoon of the first day; the7th Division was to drive directly for Hongch'on, some miles belowthe Parallel. [29] The 7th Regiment of the ROK 6th Division guarded Ch'unch'on,a beautiful town spread out below Peacock Mountain atop which stood a well-knownshrine with red lacquered pillars. An other regiment was disposed eastwardguarding the approaches to Hoengsong. The third regiment, in reserve, waswith division headquarters at Wonju, forty-five miles south of the Parallel.

The two assault regiments of the N.K. 2d Division attacked Ch'unch'onearly Sunday morning; the 6th Regiment advanced along the riverroad, while the 4th Regiment climbed over the mountains north ofthe city. From the outset, the ROK artillery was very effective and theenemy 6th Regiment met fierce resistance. Before the day ended,the 2d Division's reserve regiment, the 17th, joined in theattack. [30] Lt. Col. Thomas D. McPhail, adviser to the ROK 6th Division,proceeded to Ch'unch'on from Wonju in the morning after he received wordthat the North Koreans had crossed the Parallel. Late in the day the ROKreserve regiment arrived from Wonju. A factor of importance in Ch'unch'on'sdefense was that no passes had been issued to ROK personnel and the positionsthere were fully manned when the attack came.

The battle for Ch'unch'on was going against the North Koreans. Fromdug-in concrete pillboxes on the high ridge just north of the town theROK 6th Division continued to repel the enemy attack. The failure of theN.K. 2d Division to capture Ch'unch'on the first day, as ordered,caused the N.K. II Corps to change the attack plans of theN.K. 7th Division. This division had started from the Inje area,30 miles farther east, for Hongch'on, an important town southeast of Ch'unch'on.The II Corps now diverted it to Ch'unch'on, which it reachedon the evening of 26 June. There the 7th Division immediately joined its forces with the 2dDivision in the battle for the city. [31]

Apparently there were no enemy tanks in the Ch'unch'on battle untilthe 7th Division arrived. The battle continued through the thirdday, 27 June. The defending ROK 6th Division finally withdrew southwardon the 28th on orders after the front had collapsed on both sides of it.The North Koreans then entered Ch'unch'on. Nine T34 tanks apparently ledthe main body into the town on the morning of 28 June. [32]

The enemy 2d Division suffered heavily in the battle forCh'unch'on; its casualty rate reportedly was more than 40 percent, the6th Regiment alone having incurred more than 50 percent casualties.According to prisoners, ROK artillery fire caused most of the losses. ROKcounterbattery fire also inflicted heavy losses on enemy artillery andsupporting weapons, including destruction of 7 of the division's 16 self-propelledSU-76-mm. guns, 2 45-mm. antitank guns, and several mortars of all types.[33] The N.K. 7th Division likewise suffered considerable, but notheavy, casualties in the Ch'unch'on battle. [34]

Immediately after the capture of Ch'unch'on the 7th Division pressedon south toward Hongch'on, while the N.K. 2d Division turned westtoward Seoul.

On the east coast across the high Taebaek Range from Inje, the lastmajor concentration of North Korean troops awaited the attack hour. Therethe N.K. 5th Division, the 766th Independent Unit, and someguerrilla units were poised to cross the Parallel. On the south side ofthe border the 10th Regiment of the ROK 8th Division held defensive positions.The ROK division headquarters was at Kangnung, some fifteen miles downthe coast; the division's second regiment, the 21st, was stationed at Samch'ok,about twenty-five miles farther south. Only a small part of the 21st Regimentactually was at Samch'ok on 25 June, however, as two of its battalionswere engaged in antiguerrilla action southward in the Taeback Mountains.[35]

About 0500 Sunday morning, 25 June, Koreans awakened Maj. George D.Kessler, KMAG adviser to the 10th Regiment, at Samch'ok and told him aheavy North Korean attack was in progress at the 38th Parallel. Withina few minutes word came that enemy troops were landing at two points alongthe coast nearby, above and below Samch'ok. The commander of the 10th Regimentand Major Kessler got into a jeep and drove up the coast. From a hilltopthey saw junks and sampans lying offshore and what looked like a battalionof troops milling about on the coastal road. They drove back south, andbelow Samch'ok they saw much the same scene. By the time the two officersreturned to Samch'ok enemy craft were circling offshore there. ROK soldiers brought up theirantitank guns and opened fire on the craft. Kessler saw two boats sink.A landing at Samch'ok itself did not take place. These landings in theSamch'ok area were by guerrillas in the approximate strength of 400 aboveand 600 below the town. Their mission was to spread inland into the mountainouseastern part of Korea. [36]

Meanwhile, two battalions of the 766th Independent Unit had landednear Kangnung. Correlating their action with this landing, the N.K. 5thDivision and remaining elements of the 766th Independent Unit crossedthe Parallel with the 766th Independent Unit leading the attacksouthward down the coastal road. [37]

The American advisers to the ROK 8th Division assembled at Kangnungon 26 June and helped the division commander prepare withdrawal plans.The 10th Regiment was still delaying the enemy advance near the border.The plan agreed upon called for the 8th Division to withdraw inland acrossthe Taebaek Range and establish contact with the ROK 6th Division, if possible,in the central mountain corridor, and then to move south toward Pusan byway of Tanyang Pass. The American advisers left Kangnung that night anddrove southwest to Wonju where they found the command post of the ROK 6thDivision. [38]

On 28 June the commander of the 8th Division sent a radio message tothe ROK Army Chief of Staff saying that it was impossible to defend Kangnungand giving the positions of the 10th and 21st Regiments. The ROK 8th Divisionsuccessfully executed its withdrawal, begun on 27-28 June, bringing alongits weapons and equipment. [39]

The ROK Counterattack at Uijongbu

By 0930 Sunday morning, 25 June, the ROK Army high command at Seoulhad decided the North Koreans were engaged in a general offensive and nota repetition of many earlier "rice raids." [40]

Acting in accordance with plans previously prepared, it began movingreserves to the north of Seoul for a counterattack in the vital UijongbuCorridor. The 2d Division at Taejon was the first of the divisions distantfrom the Parallel to move toward the battle front. The first train withdivision headquarters and elements of the 5th Regiment left Taejon forSeoul at 1430, 25 June, accompanied by their American advisers. By dark,parts of the 5th Division were on their way north from Kwangju in southwestKorea. The 22d Regiment, the 3d Engineer Battalion, and the 57-mm. antitankcompany of the ROK 3d Division also started north from Taegu that night.

During the 25th, Capt. James W. Hausman, KMAG adviser with General Chae,ROK Army Chief of Staff, had accompanied the latter on two trips from Seoulto the Uijongbu area. General Chae, popularly known as the "fat boy,"weighed 245 pounds, and was about 5 feet 6 inches tall. General Chae'splan, it developed, was to launch a counterattack in the Uijongbu Corridorthe next morning with the 7th Division attacking on the left along theTongduch'on-ni road out of Uijongbu, and with the 2d Division on the righton the P'och'on road. In preparing for this, General Chae arranged to movethe elements of the 7th Division defending the P'och'on road west to theTongduch'on-ni road, concentrating that division there, and turn over tothe 2d Division the P'och'on road sector. But the 2d Division would onlybegin to arrive in the Uijongbu area during the night. It would be impossibleto assemble and transport the main body of the division from Taejon, ninetymiles below Seoul, to the front above Uijongbu and deploy it there by thenext morning.

Brig. Gen. Lee Hyung Koon, commander of the 2d Division, objected toChae's plan. It meant that he would have to attack piecemeal with smallelements of his division. He wanted to defer the counterattack until hecould get all, or the major part, of his division forward. Captain Hausmanagreed with his view. But General Chae overruled these objections and orderedthe attack for the morning of 26 June. The Capital Division at Seoul wasnot included in the counterattack plan because it was not considered tacticaland had no artillery. It had served chiefly as a "spit and polish"organization, with its cavalry regiment acting as a "palace guard."

Elements of the 7th Division which had stopped the N.K. 3d Divisionat P'och'on withdrew from there about midnight of 25 June. The nextmorning only the 2d Division headquarters and the 1st and 2d Battalionsof the 5th Regiment had arrived at Uijongbu. [41]

During the first day, elements of the 7th Division near Tongduch'on-nion the left-hand road had fought well, considering the enemy superiorityin men, armor, and artillery, and had inflicted rather heavy casualtieson the 16th Regiment of the N.K. 4th Division. But despitelosses the enemy pressed forward and had captured and passed through Tongduch'on-niby evening. [42] On the morning of 26 June, therefore, the N.K. 4thDivision with two regiments abreast and the N.K. 3d Division alsowith two regiments abreast were above Uijongbu with strong armor elements,poised for the converging attack on it and the corridor to Seoul.

On the morning of 26 June Brig. Gen. Yu Jai Hyung, commanding the ROK7th Division, launched his part of the counterattack against the N.K. 4thDivision north of Uijongbu. At first the counterattack made progress.This early success apparently led the Seoul broadcast in the afternoonto state that the 7th Division had counterattacked, killed 1,580 enemy soldiers, destroyed 58 tanks, and destroyed or captureda miscellany of other weapons. [43]

Not only did this report grossly exaggerate the success of the 7th Division,but it ignored the grave turn of events that already had taken place infront of the 2d Division. The N.K. 3d Division had withdrawn fromthe edge of P'och'on during the night, but on the morning of the 26th resumedits advance and reentered P'och'on unopposed. Its tank-led column continuedsouthwest toward Uijongbu. General Lee of the ROK 2d Division apparentlybelieved a counterattack by his two battalions would be futile for he neverlaunched his part of the scheduled counterattack. Visitors during the morningfound him in his command post, doing nothing, surrounded by staff officers.[44] His two battalions occupied defensive positions about two miles northeastof Uijongbu covering the P'och'on road. There, these elements of the ROK2d Division at 0800 opened fire with artillery and small arms on approachingNorth Koreans. A long column of tanks led the enemy attack. ROK artilleryfired on the tanks, scoring some direct hits, but they were unharmed and,after halting momentarily, rumbled forward. This tank column passed throughthe ROK infantry positions and entered Uijongbu. Following behind the tanks,the enemy 7th Regiment engaged the ROK infantry. Threatened withencirclement, survivors of the ROK 2d Division's two battalions withdrewinto the hills. [45]

This failure of the 2d Division on the eastern, right-hand, road intoUijongbu caused the 7th Division to abandon its own attack on the westernroad and to fall back below the town. By evening both the N.K. 3dand 4th Divisions and their supporting tanks of the 105th ArmoredBrigade had entered Uijongbu. The failure of the 2d Division aboveUijongbu portended the gravest consequences. The ROK Army had at hand noother organized force that could materially affect the battle above Seoul.[46]

General Lee explained later to Col. William H. S. Wright that he didnot attack on the morning of the 26th because his division had not yetclosed and he was waiting for it to arrive. His orders had been to attackwith the troops he had available. Quite obviously this attack could nothave succeeded. The really fatal error had been General Chae's plan ofoperation giving the 2d Division responsibility for the P'och'on road sectorwhen it was quite apparent that it could not arrive in strength to meetthat responsibility by the morning of 26 June.

The Fall of Seoul

The tactical situation for the ROK Army above Seoul was poor as evening fell on the second day, 26 June. Its 1st Division at Korangp'o-ri wasflanked by the enemy 1st Division immediately to the east and the4th and 3d Divisions at Uijongbu. Its 7th Division and elementsof the 2d, 5th, and Capital Divisions were fighting un-co-ordinated delayingactions in the vicinity of Uijongbu.

During the evening the Korean Government decided to move from Seoulto Taejon. Members of the South Korean National Assembly, however, afterdebate decided to remain in Seoul. That night the ROK Army headquartersapparently decided to leave Seoul. On the morning of the 27th the ROK Armyheadquarters left Seoul, going to Sihung-ni, about five miles south ofYongdungp'o, without notifying Colonel Wright and the KMAG headquarters.[47]

Ambassador Muccio and his staff left Seoul for Suwon just after 0900on the 27th. Colonel Wright and KMAG then followed the ROK Army headquartersto Sihung-ni. There Colonel Wright persuaded General Chae to return toSeoul. Both the ROK Army headquarters and the KMAG headquarters were backin Seoul by 1800 27 June. [48]

The generally calm atmosphere that had pervaded the Seoul area duringthe first two days of the invasion disappeared on the third. The failureof the much discussed counterattack of the ROK 7th and 2d Divisions andthe continued advance of the North Korean columns upon Seoul became knownto the populace of the city during 27 June, and refugees began crowdingthe roads. During this and the preceding day North Korean planes droppedleaflets on the city calling for surrender. Also, Marshal Choe Yong Gun,field commander of the North Korean invaders, broadcast by radio an appealfor surrender. [49] The populace generally expected the city to fall duringthe night. By evening confusion took hold in Seoul.

A roadblock and demolition plan designed to slow an enemy advance hadbeen prepared and rehearsed several times, but so great was the terrorspread by the T34 tanks that "prepared demolitions were not blown,roadblocks were erected but not manned, and obstacles were not coveredby fire." But in one instance, Lt. Col. Oum Hong Sup, Commandant ofthe ROK Engineer School, led a hastily improvised group that destroyedwith demolitions and pole charges four North Korean tanks at a mined bridgeon the Uijongbu-Seoul road. [50] A serious handicap in trying to stop theenemy tanks was the lack of antitank mines in South Korea at the time ofthe invasion-only antipersonnel mines were available. [51]

Before midnight, 27 June, the defenses of Seoul had all but fallen. The 9th Regiment, N.K. 3d Division,was the first enemy unit to reach the city. Its leading troops arrivedin the suburbs about 1930 but heavy fire forced them into temporary withdrawal.[52] About 2300 one lone enemy tank and a platoon of infantry entered theSecret Gardens at Chang-Duk Palace in the northeast section of the city.Korean police managed to destroy the tank and kill or disperse the accompanyingsoldiers. [53]

Lt. Col. Peter W. Scott at midnight had taken over temporarily the G-3adviser desk at the ROK Army headquarters. When reports came in of breaksin the line at the edge of Seoul he saw members of the ROK Army G-3 Sectionbegin to fold their maps. Colonel Scott asked General Chae if he had orderedthe headquarters to leave; the latter replied that he had not. [54]

About midnight Colonel Wright ordered some of the KMAG officers to goto their quarters and get a little rest. One of these was Lt. Col. WalterGreenwood, Jr., Deputy Chief of Staff, KMAG. Soon after he had gone tobed, according to Colonel Greenwood, Maj. George R. Sedberry, Jr., theG-3 adviser to the ROK Army, telephoned him that the South Koreans intendedto blow the Han River bridges. Sedberry said that he was trying to persuadeGeneral Kim Paik Il, ROK Deputy Chief of Staff, to prevent the blowingof the bridges until troops, supplies, and equipment clogging the streetsof Seoul could be removed to the south side of the river. There had beenan earlier agreement between KMAG and General Chae that the bridges wouldnot be blown until enemy tanks reached the street on which the ROK Armyheadquarters was located. Greenwood hurried to the ROK Army headquarters.There General Kim told him that the Vice Minister of Defense had orderedthe blowing of the bridges at 0130 and they must be blown at once. [55]

Maj. Gen. Chang Chang Kuk, ROK Army G-3 at the time, states that GeneralLee, commander of the 2d Division, appeared at the ROK Army headquartersafter midnight and, upon learning that the bridges were to be blown, pleadedwith General Kim to delay it at least until his troops and their equipment,then in the city, could cross to the south side of the Han. It appearsthat earlier, General Chae, the Chief of Staff, over his protests had beenplaced in a jeep and sent south across the river. According to GeneralChang, General Chae wanted to stay in Seoul. But with Chae gone, GeneralKim was at this climactic moment the highest ranking officer at the ROKArmy headquarters. After General Lee's pleas, General Kim turned to GeneralChang and told him to drive to the river and stop the blowing of the bridge.

General Chang went outside, got into a jeep, and drove off toward thehighway bridge, but he found the streets so congested with traffic, bothwheeled and pedestrian, that he could make only slow progress. The nearestpoint from which he might expect to communicate with the demolition partyon the south side of the river was a police box near the north end of thebridge. He says he had reached a point about 150 yards from the bridgewhen a great orange-colored light illumined the night sky. The accompanyingdeafening roar announced the blowing of the highway and three railroadbridges. [55]

The gigantic explosions, which dropped two spans of the Han highwaybridge into the water on the south side, were set off about 0215 with nowarning to the military personnel and the civilian population crowdingthe bridges.

Two KMAG officers, Col. Robert T. Hazlett and Captain Hausman, on theirway to Suwon to establish communication with Tokyo, had just crossed thebridge when it blew up-Hausman said seven minutes after they crossed. Hazlettsaid five minutes. Hausman places the time of the explosion at 0215. Severalother sources fix it approximately at the same time. Pedestrian and solidvehicular traffic, bumper to bumper, crowded all three lanes of the highwaybridge. In Seoul the broad avenue leading up to the bridge was packed inall eight lanes with vehicles of all kinds, including army trucks and artillerypieces, as well as with marching soldiers and civilian pedestrians. Thebest informed American officers in Seoul at the time estimate that between500 and 800 people were killed or drowned in the blowing of this bridge.Double this number probably were on that part of the bridge over waterbut which did not fall, and possibly as many as 4,000 people altogetherwere on the bridge if one includes the long causeway on the Seoul sideof the river. Three American war correspondents-Burton Crane, Frank Gibney,and Keyes Beech-were just short of the blown section of the bridge whenit went skyward. The blast shattered their jeep's windshield. Crane andGibney in the front seat received face and head cuts from the flying glass.Just ahead of them a truckload of ROK soldiers were all killed. [57]

There was a great South Korean up roar later over the premature destructionof the Han River bridges, and a court of inquiry sat to fix the blame forthe tragic event. A Korean army court martial fixed the responsibilityand blame on the ROK Army Chief Engineer for the "manner" inwhich he had prepared the bridges for demolition, and he was summarilyexecuted. Some American advisers in Korea at the time believed that GeneralChae ordered the bridges blown and that the Chief Engineer merely carriedout his orders. General Chae denied that he had given the order. Othersin a good position to ascertain all the facts available in the prevailingconfusion believed that the Vice Minister of Defense ordered the blowing of the bridges. The statements attributedto General Kim support this view.

The utter disregard for the tactical situation, with the ROK Army stillholding the enemy at the outskirts of the city, and the certain loss ofthousands of soldiers and practically all the transport and heavy weaponsif the bridges were destroyed, lends strong support to the view that theorder was given by a ROK civilian official and not by a ROK Army officer.

Had the Han River bridges not been blown until the enemy actually approachedthem there would have been from at least six to eight hours longer in whichto evacuate the bulk of the troops of three ROK divisions and at leasta part of their transport, equipment, and heavy weapons to the south sideof the Han. It is known that when the KMAG party crossed the Han Riverat 0600 on 28 June the fighting was still some distance from the river,and according to North Korean sources enemy troops did not occupy the centerof the city until about noon. Their arrival at the river line necessarilymust have been later.

The premature blowing of the bridges was a military catastrophe forthe ROK Army. The main part of the army, still north of the river, lostnearly all its transport, most of its supplies, and many of its heavy weapons.Most of the troops that arrived south of the Han waded the river or crossedin small boats and rafts in disorganized groups. The disintegration ofthe ROK Army now set in with alarming speed.

ROK troops held the North Koreans at the edge of Seoul throughout thenight of 27-28 June, and the North Koreans have given them credit for puttingup a stubborn resistance. During the morning of the 28th, the North Koreanattack forced the disorganized ROK defenders to withdraw, whereupon streetfighting started in the city. Only small ROK units were still there. Thesedelayed the entry of the N.K. 3d Division into the center of Seouluntil early afternoon. [58] The 16th Regiment of the N.K. 4thDivision entered the city about mid-afternoon. [59] One group of ROKsoldiers in company strength dug in on South Mountain within the city andheld out all day, but finally they reportedly were killed to the last man.[60] At least a few North Korean tanks were destroyed or disabled in streetfighting in Seoul. One captured North Korean tanker later told of seeingtwo knocked-out tanks in Seoul when he entered. [61] The two North Koreandivisions completed the occupation of Seoul during the afternoon. Withinthe city an active fifth column met the North Korean troops and helpedthem round up remaining ROK troops, police, and South Korean governmentofficials who had not escaped.

In the first four days of the invasion, during the drive on Seoul, theN.K. 3d and 4th Divisions incurred about 1,500 casualties.[62] Hardest hit was the 4th Division, which had fought the ROK 7th Division down to Uijongbu.It lost 219 killed, 761 wounded, and 132 missing in action for a totalof 1,112 casualties. [63]

In an order issued on 10 July, Kim Il Sung honored the N.K. 3d and4th Divisions for their capture of Seoul by conferring on them thehonorary title, "Seoul Division." The 105th ArmoredBrigade was raised by the same order to division status and receivedthe same honorary title. [64]

Of the various factors contributing to the quick defeat of the ROK Army,perhaps the most decisive was the shock of fighting tanks for the firsttime. The North Koreans had never used tanks in any of the numerous borderincidents, although they had possessed them since late 1949. It was on25 June, therefore, that the ROK soldier had his first experience withtanks. The ROK soldier not only lacked experience with tanks, he also lackedweapons that were effective against the T34 except his own handmade demolitioncharge used in close attack. [65]

Seoul fell on the fourth day of the invasion. At the end of June, aftersix days, everything north of the Han River had been lost. On the morningof 29 June, General Yu Jai Hyung with about 1,200 men of the ROK 7th Divisionand four machine guns, all that was left of his division, defended thebridge sites from the south bank of the river. In the next day or two remnantsof four South Korean divisions assembled on the south bank or were stillinfiltrating across the river. [66] Colonel Paik brought the ROK 1st Division,now down to about 5,000 men, across the Han on 29 June in the vicinityof Kimpo Airfield, twelve air miles northwest of Seoul. He had to leavehis artillery behind but his men brought out their small arms and mostof their crew-served weapons. [67]

Of 98,000 men in the ROK Army on 25 June the Army headquarters couldaccount for only 22,000 south of the Han at the end of the month. [68]When information came in a few days later about the 6th and 8th Divisionsand more stragglers assembled south of the river, this figure increasedto 54,000. But even this left 44,000 completely gone in the first weekof war-killed, captured, or missing. Of all the divisions engaged in theinitial fighting, only the 6th and 8th escaped with their organization,weapons, equipment, and transport relatively intact. Except for them, theROK Army came out of the initial disaster with little more than about 30percent of its individual weapons. [69]

[1] New York Times, June 27, 1950. An enterprising Times employee found this manifesto and accompanying Tass article in Izvestia, June 10, 1950, datelined Pyong [P'yongyang], in the Library of Congress and had it translated from the Russian.

[2] GHQ FEC, History of the N.K. Army; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts for the various North Korean divisions.

[3] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 2 (Documentary Evidence of N.K. Aggression), pt. 2; The Conflict in Korea, pp. 26-28, 32-36.

[4] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 2, pt. 2, pp. 12-23.

[5] Ibid., Opn Orders 4th Inf Div, 22 Jun 50, Transl 200045. This document includes an annex giving a breakdown of regimental attack plans. The Conflict in Korea, pages 28-32, gives part of the document.

[6] The Conflict in Korea, pp. 12-69; ATIS Enemy Documents, Korean Opns, Issue 1, item 3, p. 37; Ibid., item 6, p. 43.

[7] Schnabel, Theater Command, ch. IV, p. 5; New York Times, Sept. 15, 1950.

[8] Norman Bartlett, With the Australians in Korea (Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1954), p. 166; Time Magazine, June 5, 1950, pp. 26-27. The New York Times, June 26, 1950, gives General Roberts' views as reported by Lindsay Parrott in Tokyo.

[9] The time used is for the place where the event occurred unless otherwise noted. Korean time is fourteen hours later than New York and Washington EST and thirteen hours later than EDT. For example, 0400 25 June in Korea would be 1400 24 June in New York and Washington EST.

[10] Col Walter Greenwood, Jr., Statement of Events 0430, 25 June-1200, 28 June 1950, for Capt Robert K. Sawyer, with Ltr to Sawyer, 22 Feb 54. Colonel Greenwood was Deputy Chief of Staff, KMAG, June 1950.

[11] GHQ FEC, Annual Narrative Historical Report, 1 Jan-31 Oct 50, p. 8; New York Times, June 25, 1950. That the North Korean Government actually made a declaration of war has never been verified.

[12] Transcript of the radio broadcast in 24th Div G-2 Jnl, 25 Jun.

[13] Dept of State Pub 3922, United States Policy in the Korean Crisis, Document 10 (U.N. Commission on Korea, Report to the Secretary-General), pp. 18 - 20.

[14] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 100 (N.K. 6th Div), p. 32; Interv, author with Hausman, 12 Jan 52; KMAG G-2 Unit Hist, 25 Jun 50.

[15] Sawyer, KMAG MS, pt. III.

[16] Ibid.; Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer.

[17] Interv, Schnabel with Schwarze; DA Wkly Intel Rpt, 30 Jun 50, Nr 71, p. 10.

[18] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 100 (N.K. 6th Div), p. 33.

[19] Ltr, Col Rockwell to author, 21 May 54; Gen Paik Sun Yup, MS review comments, 11 Jul 58.

[20] Interv, author with Capt Joseph R. Darrigo, 5 Aug 53: Ltr, Maj William E. Hamilton to author, 29 Jul 53. Major Hamilton on 25 June 1950 was adviser to the ROK 12th Regiment. He said several ROK officers of the 12th Regiment who had escaped from Kaesong, including the regimental commander with whom he had talked, confirmed Darrigo's story of the North Korean entrance into Kaesong by train. See also, Ltr, Rockwell to author, 21 May 54; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 100 (N.K. 6th Div), p. 32: 24th Div G-3 Jnl, 25 Jun 50.

[21] Ltr, Rockwell to author, 21 May 54; Interv, author with Darrigo, 5 Aug 53; Ltr, Hamilton to author, 21 Aug 53; Gen Paik, MS review comments, 11 Jul 58.

[22] Ltr, Rockwell to author, 21 May 54; Ltr, Hamilton to author, 21 Aug 53; Gen Paik, MS review comments, 1 Jul 58.

[23] Ltr, Rockwell to author, 21 May 54; Interv, author with Hausman, 12 Jan 52. Colonel Paik some days after the action gave Hausman an account of the Imjin River battle. Paik estimated that about ninety ROK soldiers gave their lives in attacks on enemy tanks.

[24] Interv, author with Hausman, 12 Jan 52 (related by Paik to Hausman).

[25] DA Intel Rev, Mar 51, Nr ·78, p. 34; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 2 (Documentary Evidence of N.K. Aggression), pt. II, Opn Ord Nr 1, 4th Inf Div, 22 Jun 50; Ibid., Issue 3 (Enemy Documents), p. 65; G-2 Periodic Rpt, 30 Jun 50, Reserve CP (N.K.); The Conflict in Korea, p. 28.

[26] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 4 (Enemy Forces), p. 37; Ibid., Issue 2 (Documentary Evidence of N.K. Aggression), p. 45; Opn Plan, N.K. 4th Inf Div. Opn Ord Nr I. 221400 Jun 50; Ibid., Issue 94 (N.K. 4th Div), Ibid., Issue 96 (N.K. 3d Div).

[27] Interv, author with Gen Chang, 14 Oct 53; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 3 (Enemy Documents), p. 5, file 25 Jun-9 Jul 50.

[28] Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer; Schwarze, Notes for author, 13 Oct 53; 24th Div G-2 Jnl, 25 Jun 50; New York Times, June 26, 1950.

[29] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 9 (N.K. Forces), pp. 158-74, Interrog Nr 1468 (Sr Col Lee Hak Ku, N.K. II Corps Opns Off at time of invasion.

[30] Ibid., Issue 94 (N.K. 2d Div), p. 33; 24th Div. G-2 Jnl, 25 Jun 50; Ltr, Lt Col Thomas D. McPhail to author, 28 Jun 54; New York Times, June 25, 1950.

[31] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 99 (N.K. 12th Div), p. 43; Ibid., Issue 2 (Documentary Evidence of N.K. Aggression), p. 22; KMAG G-2 Unit Hist, 25 Jun 50; DA Intel Rev, Mar 51, p. 34; Rpt, USMAG to ROK, 1 Jan-15 Jun 50, Annex IV, 15 Jun 50.

[32] Ltr, McPhail to author, 28 Jun 54; KMAG G-2 Unit Hist, 28 Jun 50; 24th Div G-3 Jnl, 30 Jun 50.

[33] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 94 (N.K. 2d Div), pp. 33-34; Ibid., Issue 106 (N.K. Arty), p. 51.

[34] Ibid., Issue 99 (N.K. 12th Div), p. 43.

[35] Interv, Sawyer with Col George D. Kessler, 24 Feb 54; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 96 (N.K. 5th Div), p. 39; KMAG G-2 Unit Hist, 25 Jun 50.

[36] Interv, Sawyer with Kessler 24 Feb 54; 24th Div G-3 Jnl, 25 Jun 50; DA Wkly Intel Rpt, Nr 72, 7 Jul 50, p. 18.

[37] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 2 (Documentary Evidence of N.K. Aggression), pp. 46-50; Ibid., Issue 96 (N.K. 5th Div), p. 39; 24th Div G-3 Jnl, 25 Jun 50; DA Wkly Intel Rpt, Nr 72, 7 Jul 50, p. 18; KMAG G-2 Unit Hist, 25 Jun 50. According to North Korean Col. Lee Hak Ku, the 17th Motorcycle Regiment also moved to Kangnung but the terrain prevented its employment in the attack. See ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 9 (N.K. Forces), pp. 158-74, Nr 1468.

[38]Interv, Sawyer with Kessler, 24 Feb 54.

[39] Ibid.; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 3 (Enemy Documents), pp. 28, 45, file 25 Jun-9 Jul 50. On the 29th the 8th Division reported its strength as 6,135.

[40] Interv, author with Gen Chang. 14 Oct 53.

[41] Interv, author with Hausman, 12 Jan 52; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 96 (N.K. 3d Div), p. 29; EUSAK WD, G-2 Sec, 20 Jul50, ATIS Interrog Nr 89 (2d Lt Pak Mal Bang, escapee from North Korea, a memberof the ROK 5th Regt at Uijongbu on 26 Jun).

[42] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 94 (N.K. 4th Div), p.44; Ibid., Issue 2 (Documentary Evidence of N.K. Aggression), Recon Ord Nr 1 to4th Div.

[43] 24th Div G-2 Jnl, 26 Jun 50. The New York Times, June 26, 1950, carries an optimistic statement by the South Korean cabinet.

[44] Interv, Dr. Gordon W. Prange and Schnabel with Lt Col Nicholas J. Abbott, 6 Mar 51; EUSAK WD G-2 Sec, 20 Jul 50, ATIS Interrog Nr 89 (Lt Pak Mal Bang).

[45] EUSAK WD, G-2 Sec, 20 Jul 50, ATIS Interrog 89 (Lt Pak Mal Bang); ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 96 (N.K. 3d Div), p. 29.

[46] Interv, author with Col Wright, 3 Jan 52; Interv, Prange and Schnabel with Abbott, 6 Mar 51; Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer, 22 Feb 54; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue I (Enemy Documents), item 6, p. 43; 24th Div G-2 Jnl, 26 Jun 50.

[47] Interv, author with Col Robert T. Hazlett, 14 Jun 51 (Hazlett was

adviser to the ROK Infantry School, June 1950); Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer, 22 Feb 54; Sawyer, KMAG MS, pt. III; Col Wright, Notes for author, 1952; Soon-Chun Pak, "What Happened to a Congress Woman," in John W. Riley, Jr., and Wilbur Schram, The Reds Take a City (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1951), p. 193. Sihung-ni had been a cantonment area of the ROK Infantry School before the invasion.

[48] Sawyer, KMAG MS; Wright, Notes for author, 1952.

[49] The New York Times, June 17, 1950; DA Intel Rev, Aug 50, Nr 171, p. 18

[50] Wright, Notes for author, 1952.

[51] Maj. Richard I. Crawford, Notes on Korea, 25 June-5 December 1950, typescript of talk given by Crawford at Ft. Belvoir, Va., 17 Feb 51. (Crawford was senior engineer adviser to the ROK Army in June 1950.)

[52] Diary found on dead North Korean, entry 27 Jun 50, in 25th Div G-2 PW Interrog File, 2-22 Jul 50; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 96 (N.K. 3d Div), p. 30.

[53] Intervs, author with Gen Chang, 14 Oct 53, Schwarze, 3 Feb 54, and Hausman, 12 Jan 54. Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer, 22 Feb 54. The rusting hulk of this tank was still in the palace grounds when American troops recaptured the city in September.

[54] Copy of Ltr, Col Scott to unnamed friend, n.d. (ca. 6-7 Jul 50). Colonel Scott was the G-1 adviser to ROK Army.

[55] Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer, 22 Feb 54; Ltr, Greenwood to author, 1 Jul 54; Interv, author with Col Lewis D. Vieman (KMAG G-4 adviser), 15 Jun 54. Sedberry said he did not remember this conversation relating to blowing the Han River bridge. Ltr, Sedberry to author, 10 Jun 54.

[56] Interv, author with Gen Chang, 14 Oct 53.

[57] Wright, Notes for author, 1952; Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer, 22 Feb 54; Lt Col Lewis D. Vieman, Notes on Korea, typescript, 15 Feb 51; Interv, author with Hausman, 12 Jan 52; Interv, author with Keyes Beech, 1 Oct 51; Interv, author with Hazlett, 11 Jun 54. The New York Times, June 29, 1950, carries Burton Crane's personal account of the Han bridge destruction.

[58] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 96 (N.K. 3d Div), p. 30. The time given for the entry into Seoul is 1300.

[59] Ibid., Issue 94 (N.K. 4th Div), p. 44. GHQ FEC, History of the N.K. Army, p. 44, claims that the 18th Regiment, N.K. 4th Division, entered Seoul at 1130, 28 June. The P'yongyang radio broadcast that the North Korea People's Army occupied Seoul at 0300, 28 June. See 24th Div G-2 Msg File, 28 Jun 50.

[60] Interv, author with Schwarze, 3 Feb 54; KMAG G-s Unit Hist, 28 Jun 50.

[61] ORO-R-I (FEC), 8 Apr 51, The Employment of Armor in Korea, vol. I, p. 156.

[62] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 94 (N.K. 4th Div), p. 44; Ibid., Issue 96 (N.K. 3d Div), p. 30; Ibid., Issue I (Enemy Documents), p. 37.

[63] GHQ FEC, History of the N.K. Army (4th Div), p. 58. Theses figures are based on a captured enemy casualty report.

[64] GHQ FEC, History of the N.K. Army, p. 56.

[65] On Friday, 30 June, the sixth day of the invasion, the first antitank mines arrived in Korea. Eight hundred of them were flown in from Japan. Crawford, Notes on Korea.

[66] Ltr, Greenwood to author, 1 Jul 54.

[67] Interv, author with Hazlett, 11 Jun 54. Hazlett was at Sihung-ni, reconnoitering a crossing, when Colonel Paik arrived there the evening of 28 June, and talked with him later about the division's crossing.

[68] Interv, author with Hausman, 12 Jan 54.

[69] Ibid.; Vieman, Notes on Korea, 15 Feb 51; Interv, author with Gen Chang, 14 Oct 53. General Chang estimated there were 40,000 soldiers under organized ROK Army command 1 July. General MacArthur on 29 June placed the number of ROK Army effectives at 25,000.

|

|

- A VETERAN's Blog - |