|

|

CHAPTER VThe North Koreans Cross the Han River |

The Foundation of Freedom is the Courage of Ordinary PeopleHistory |

| The nature of armies is determined by the nature of the civilizationin which they exist. |

| BASIL HENRY LIDDELL HART, The Ghost of Napoleon |

Deployment of U.S. Forces in the Far East, June 1950

At the beginning of the Korean War, United States Army ground combatunits comprised 10 divisions, the European Constabulary (equivalent to1 division), and 9 separate regimental combat teams. [1] The Army's authorizedstrength was 630,000; its actual strength was 592,000. Of the combat units,four divisions-the 7th, 24th, and 25th Infantry Divisions and the 1st CavalryDivision (infantry)-were in Japan on occupation duty. Also in the Pacificwere the 5th Regimental Combat Team in the Hawaiian Islands and the 29thRegiment on Okinawa. The divisions, with the exception of the one in Europe,were under-strength, having only two instead of the normal three battalionsin an infantry regiment, and they had corresponding shortages in the othercombat arms. The artillery battalions, for instance, were reduced in personneland weapons, and had only two of the normal three firing batteries. Therewas one exception in the organizations in Japan. The 24th Regiment, 25thDivision, had a normal complement of three battalions, and the 159th FieldArtillery Battalion, its support artillery, had its normal complement ofthree firing batteries.

The four divisions, widely scattered throughout the islands of Japan,were under the direct control of Eighth Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. WaltonH. Walker. The 7th Division, with headquarters near Sendai on Honshu, occupiedthe northernmost island at Hokkaido and the northern third of Honshu. The1st Cavalry Division held the populous central area of the Kanto Plainin Honshu, with headquarters at Camp Drake near Tokyo. The 25th Divisionwas in the southern third of Honshu with headquarters at Osaka. The 24thDivision occupied Kyushu, the southernmost island of Japan, with headquartersat Kokura, across the Tsushima (Korea) Strait from Korea. These divisionsaveraged about 70 percent of full war strength, three of them numberingbetween 12,000 and 13,000 men and one slightly more than 15,000. [2] They did not have their full wartimeallowances of 57-mm. and 75-mm. recoilless rifles and 4.2-inch mortars.The divisional tank units then currently organized had the M24 light tank.Nearly all American military equipment and transport in the Far East hadseen World War II use and was worn.

In June 1950, slightly more than one-third of the United States navaloperating forces were in the Pacific under the command of Admiral ArthurW. Radford. Only about one-fifth of this was in Far Eastern waters. ViceAdm. Charles Turner Joy commanded U.S. Naval Forces, Far East. The navalstrength of the Far East Command when the Korean War started comprised1 cruiser, the Juneau; 4 destroyers, the Mansfield, Dehaven,Collett, and Lyman K. Swenson; and a number of amphibious andcargo-type vessels. Not under MacArthur's command, but also in the FarEast at this time, was the Seventh Fleet commanded by Vice Adm. ArthurD. Struble. It comprised 1 aircraft carrier, the Valley Forge; 1heavy cruiser, the Rochester; 8 destroyers, a naval oiler, and 3submarines. Part of the Seventh Fleet was at Okinawa; the remainder wasin the Philippines. [3]

The Fleet Marine Force was mostly in the United States. The 1st MarineDivision was at Camp Pendleton, Calif.; the 2d Marine Division at CampLejeune, N.C. One battalion of the 2d Marine Division was in the Mediterraneanwith fleet units.

At the beginning of hostilities in Korea, the U.S. Air Force consistedof forty-eight groups. The largest aggregation of USAF strength outsidecontinental United States was the Far East Air Forces (FEAF), commandedby General Stratemeyer. On 25 June, there were 9 groups with about 350combat-ready planes in FEAF. Of the 18 fighter squadrons, only 4, thosebased on Kyushu in southern Japan, were within effective range of the combatzone in Korea. There were a light bomb wing and a troop carrier wing inJapan. The only medium bomb wing (B-29's) in the Far East was on Guam.

At the end of May 1950, FEAF controlled a total of 1,172 aircraft, includingthose in storage and being salvaged, of the following types: 73 B-26's;27 B-29's; 47 F-51's; 504 F-80's; 42 F-82's; 179 transports of all types;48 reconnaissance planes; and 252 miscellaneous aircraft. The Far EastAir Forces, with an authorized personnel strength of 39,975 officers andmen, had 33,625 assigned to it. [5]

Commanding the United States armed forces in the Far East on 25 June1950 was General MacArthur. He held three command assignments: (1) as SupremeCommander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) he acted as agent for the thirteennations of the Far Eastern Commission sitting in Washington directing the occupation of Japan; (2) asCommander in Chief, Far East (CINCFE), he commanded all U.S. military forces-Army,Air, and Navy-in the western Pacific of the Far East Command; and (3) asCommanding General, U.S. Army Forces, Far East, he commanded the U.S. Armyin the Far East. On 10 July, General MacArthur received his fourth commandassignment-Commander in Chief, United Nations Command. The General Headquarters,Far East Command (GHQ FEC), then became the principal part of General Headquarters,United Nations Command (GHQ UNC).

Nearly a year before, General MacArthur had established on 20 August1949 the Joint Strategic Plans and Operations Group (JSPOG), composed ofArmy, Navy, and Air Force representatives. This top planning group, underthe general control of General Wright, G-3, Far East Command, served asthe principal planning agency for the U.N. Command in the Korean War.

In the two or three days following the North Korean crossing of theParallel, air units moved hurriedly from bases in Japan distant from Koreato those nearest the peninsula. Most of the fighter and fighter-bombersquadrons moved to Itazuke and Ashiya Air Bases, which had the most favorablepositions with respect to the Korean battle area. Bombers also moved closerto the combat zone; twenty B-29's of the 19th Bombardment Group, TwentiethAir Force, had moved from Guam to Kadena Airfield on Okinawa by 29 June.[6]

The air action which began on 26 June continued during the followingdays. One flight of U.S. planes bombed targets in Seoul on the 28th. Enemyplanes destroyed two more American planes at Suwon Airfield during theday. [7]

Land-based planes of the Far East Air Forces began to strike hard atthe North Koreans by the end of June. On the 28th, the Fifth Air Forceflew 172 combat sorties in support of the ROK Army and comparable supportcontinued in ensuing days. General Stratemeyer acted quickly to augmentthe number of his combat planes by taking approximately 50 F-51's out ofstorage. On 30 June he informed Washington that he needed 164 F-80C's,21 F-82's, 23 B-29's, 21 C-54's, and 64 F-51's. The Air Force informedhim that it could not send the F-80's, but would substitute 150 F-51'sin excellent condition. The F-51 had a greater range than the F-80, usedless fuel, and could operate more easily from the rough Korean airfields.[8]

Of immediate benefit to close ground support were the two tactical aircontrol parties from the Fifth Air Force that arrived at Taejon on 3 July.These two TACP were being formed in Japan for an amphibious maneuver whenthe war started. They went into action on 5 July and thereafter there wasgreat improvement in the effectiveness of U.N. air support and fewer mistakenstrikes by friendly planes on ROK forces which, unfortunately, had characterizedthe air effort in the last days of June and the first days of July.

Concurrently with the initiation of air action, the naval forces inthe Far East began to assume their part in the conflict. On 28 June theAmerican cruiser Juneau arrived off the east coast of Korea, andthe next day shelled the Kangnung-Samch'ok area where North Korean amphibiouslandings had occurred. [9] American naval forces from this date forwardtook an active part in supporting American and ROK forces in coastal areasand in carrying out interdiction and bombardment missions in enemy rearareas. Naval firepower was particularly effective along the east coastalcorridor.

Acting on instructions he had received from Washington on 1 July toinstitute a naval blockade of the Korean coast, General MacArthur tooksteps to implement the order. Just after midnight, 3 July, he dispatcheda message to Washington stating that an effective blockade required patrollingthe ports of Najin, Ch'ongjin, and Wonsan on the east coast, Inch'on, Chinnamp'o,Anju, and Sonch'on on the west coast, and any South Korean ports that mightfall to the North Koreans. In order to keep well clear of the coastal watersof Manchuria and the USSR, General MacArthur said, however, that he wouldnot blockade the ports of Najin, Ch'ongjin, and Sonch'on. On the east coasthe planned naval patrols to latitude 41° north and on the west coastto latitude 38° 30' north. General MacArthur said his naval forceswould be deployed on 4 July to institute the blockade within the limitsof his existing naval forces. [10]

Admiral Joy received from General MacArthur instructions with respectto the blockade and instituted it on 4 July. [11]

Three blockade groups initially executed the blockade plan: (1) an eastcoast group under American command, (2) a west coast group under Britishcommand, and (3) a south coast group under ROK Navy command.

Before the organization of these blockade groups, the cruiser U.S.S.Juneau and 2 British ships at daylight on 2 July sighted 4 NorthKorean torpedo boats escorting 10 converted trawlers close inshore makingfor Chumunjin-up on the east coast of Korea. The Juneau and thetwo British ships turned to engage the North Korean vessels, and the torpedoboats at the same time headed for them.

The first salvo of the naval guns sank 2 of the torpedo boats, and theother 2 raced away. Naval gunfire then sank 7 of the 10 ships in the convoy;3 escaped behind a breakwater. [12]

The first U.N. carrier-based air strike of the war came on 3 July byplanes from the U.S.S. Valley Forge and the British Triumph,of Vice Admiral Struble's Seventh Fleet, against the airfields of theP'yongyang-Chinnamp'o west coast area. [13]

The River Crossing

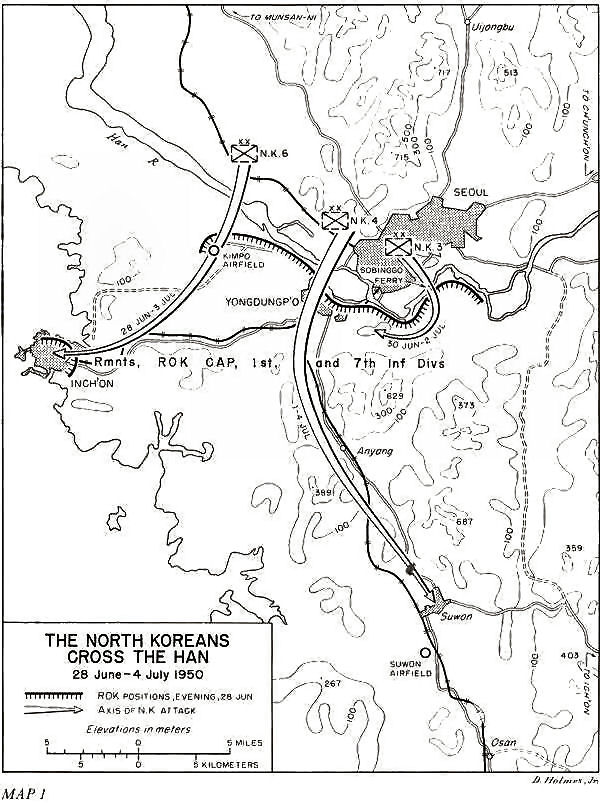

While United States air and naval forces were delivering their firstblows of the war, the South Koreans were trying to reassemble their scatteredforces and reorganize them along the south bank of the Han River. (SeeMap 1). On the 29th, when General MacArthur and his party visited theHan River, it seemed to them that elements of only the ROK 1st and 7thDivisions there might be effective within the limits of the equipment theyhad salvaged. Parts of the 5th Division were in the Yongdungp'o area oppositeSeoul, and, farther west, elements of the Capital Division still held Inch'on.Remnants of the 2d Division were eastward in the vicinity of the confluenceof the Han and Pukhan Rivers; the 6th Division was retreating south ofCh'unch'on in the center of the peninsula toward Wonju; and, on the eastcoast, the 8th Division had started to withdraw inland and south. The 23dRegiment of the ROK 3d Division had moved from Pusan through Taegu to Ulchinon the east coast, sixty-five miles above Pohang-dong, to block an anticipatedenemy approach down the coastal road. [14]

On the last day of the month, American planes dropped pamphlets overSouth Korea bearing the stamp of the United Nations urging the ROK soldiers,"Fight with all your might," and promising, "We shall supportyour people as much as we can and clear the aggressor from your country."

Meanwhile, the victorious North Koreans did not stand idle. The sameday that Seoul fell, 28 June, elements of the enemy's 6th Division startedcrossing the Han River west of the city in the vicinity of Kimpo Airfieldand occupied the airfield on the 29th. [15] (Map 1) Aftercapturing Seoul the North Korean 3d and 4th Divisions spenta day or two searching the city for South Korean soldiers, police, and"national traitors," most of whom they shot at once. The NorthKoreans at once organized "People's Committees" from South KoreanCommunists to assume control of the local population. They also took stepsto evacuate a large part of the population. Within a week after occupyingSeoul, the victors began to mobilize the city's young men for service inthe North Korean Army. [16]

The N.K. 3d Division, the first into Seoul, was also thefirst to carry the attack to the south side of the Han River opposite thecity. It spent only one day in preparation. North Korean artillery firewhich had fallen on the south side of the Han sporadically on 28 and 29June developed in intensity the night of the 29th. The next morning, 30June, under cover of artillery and tank fire the 8th Regiment crossedfrom Seoul to the south side of the Han in the vicinity of the Sobinggoferry. Some of the men crossed in wooden boats capable of carrying a 21/2-ton truck or twenty to thirty men. Others crossed the river by wadingand swimming. [17] These troops drove the South Koreans from the southbank in some places and began to consolidate positions there. But they did notpenetrate far that first day nor did they occupy Yongdungp'o, the big industrialsuburb of Seoul south of the river and the key to the road and rail netleading south. General Church directed General Chae to counterattack theNorth Koreans at the water's edge, but enemy artillery prevented the ROKtroops from carrying out this order.

The enemy's main crossing effort, aimed at Yongdungp'o, came the nextmorning. The 4th Division prepared to make the attack. For the assaultcrossing, it committed its 5th Regiment which had been in reserveall the way from the 38th Parallel to Seoul. The 3d Battalion ofthe regiment started crossing the river southwest of Seoul at 0400 1 July,and upon reaching the south side it immediately began a two-day battlefor Yongdungp'o. The remainder of the 4th Division followed thelead battalion across the river and joined in the battle. Yongdungp'o fellto the division about 0800 3 July. ROK troops waged a bitter battle andNorth Korean casualties were heavy. The enemy 4th Division lost227 killed, 1,822, wounded, and 107 missing in action at Yongdungp'o. [18]

The North Koreans fought the battle for Yongdungp'o without tank supportand this may account in large part for the ROK troops' stubborn defenseand excellent showing there. The first North Korean tanks crossed the HanRiver on 3 July after one of the railroad bridges had been repaired anddecked for tank traffic. Four enemy tanks were on the south side by midmorning.[19] While the battle for Yongdungp'o was in progress, the remainder ofthe N.K. 3d Division crossed the Han on 3 July. As the battle forYongdungp'o neared its end, part of the N.K. 6th Division reachedthe edge of Inch'on. That night an enemy battalion and six tanks enteredthe port city.

By the morning of 4 July two of the best divisions of the North KoreanPeople's Army stood poised at Yongdungp'o. With tank support at hand theywere ready to resume the drive south along the main rail-highway axis belowthe Han River.

ADCOM Abandons Suwon

On the first day of the invasion, President Syngman Rhee, AmbassadorMuccio, and KMAG notified United States authorities of the need for animmediate flow of military supplies into Korea for the ROK Army. [20] GeneralMacArthur with Washington's approval, ordered Eighth Army to ship to Pusanat once 105,000 rounds of 105-mm. howitzer, 265,000 rounds of 81-mm. mortar,89,000 rounds of 60-mm. mortar, and 2,480,000 rounds of .30-caliber ballammunition. The Sergeant Keathley, a Military Sea TransportationService (MSTS) ship, left North Pier, Yokohama, at midnight 27 June boundfor Pusan, Korea, with 1,636 long tons of ammunition and twelve 105-mm.howitzers on board. Early the next day, 28 June, a second ship, the MSTSCardinal O'Connell, feverishly loaded a cargo from the Ikego AmmunitionDepot. Airlift of ammunition began also on the 28th from Tachikawa AirBase near Tokyo. The first C-54 loaded with 105-mm. howitzer shells tookoff at 0600 28 June for Suwon, Korea. [21] By 1517 in the afternoon, transportplanes had departed Japan with a total of 119 tons of ammunition.

In ground action the situation deteriorated. At noon, 30 June, Americanobservers at the Han River sent word to General Church that the ROK riverline was disintegrating. About this time, Lt. Gen. Chung Il Kwon of theSouth Korean Army arrived from Tokyo to replace General Chae as ROK ArmyChief of Staff.

At 1600 General Church sent a radio message to Tokyo describing theworsening situation. Three hours later he decided to go to Osan (Osan-ni),twelve miles south of Suwon, where there was a commercial telephone relaystation, and from there call Tokyo. He reached Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond,MacArthur's Chief of Staff, who told him that the Far East Command hadreceived authority to use American ground troops, and that if the Suwonairstrip could be held the next day two battalions would be flown in tohelp the South Koreans. General Church agreed to try to hold the airstripuntil noon the next day, 1 July. [22]

Back at Suwon, during General Church's absence, affairs at the ADCOMheadquarters took a bad turn. A series of events were contributory. AnAmerican plane radioed a message, entirely erroneous, that a column ofenemy was approaching Suwon from the east. Generals Chae and Chung returnedfrom the Han River line with gloomy news. About dusk ADCOM and KMAG officersat the Suwon command post saw a red flare go up on the railroad about 500yards away. To one observer it looked like an ordinary railroad warningflare. However, some ADCOM officers queried excitedly, "What's that?What's that?" Another replied that the enemy were surrounding thetown and said, "We had better get out of here." There was somediscussion as to who should give the order. Colonel Wright and GeneralChurch were both absent from the command post. In a very short time peoplewere running in and out of the building shouting and loading equipment.This commotion confused the Korean officers at the headquarters who didnot understand what was happening. One of the ADCOM officers shouted thatthe group should assemble at Suwon Airfield and form a perimeter. Thereuponall the Americans drove pell-mell down the road toward the airfield, aboutthree miles away. [23]

When this panic seized the ADCOM group, communications personnel begandestroying their equipment with thermite grenades. In the resultant firethe schoolhouse command post burnt to the ground. At the airfield, thegroup started to establish a small defensive perimeter but before long they decidedinstead to go on south to Taejon. ADCOM officers ordered the antiaircraftdetachment at the airfield to disable their equipment and join them. About2200, the column of ADCOM, KMAG, AAA, and Embassy vehicles assembled andwas ready to start for Taejon. [24]

At this point, General Church returned from Osan and met the assembledconvoy. He was furious when he learned what had happened, and ordered theentire group back to Suwon. Arriving at his former headquarters buildingGeneral Church found it and much of the signal equipment there had beendestroyed by fire. His first impulse was to hold Suwon Airfield but, onreflection, he doubted his ability to keep the field free of enemy fireto permit the landing of troops. So, finally, in a downpour of rain thelittle cavalcade drove south to Osan. [25]

General Church again telephoned General Almond in Tokyo to acquainthim with the events of the past few hours, and recommended that ADCOM andother American personnel withdraw to Taejon. Almond concurred. In thisconversation Almond and Church agreed, now that Suwon Airfield had beenabandoned, that the American troops to be airlifted to Korea during 1 Julyshould come to Pusan instead. [26] In the monsoon downpour General Churchand the American group then continued on to Taejon where ADCOM establishedits new command post the morning of 1 July.

At Suwon everything remained quiet after the ADCOM party departed. ColonelsWright and Hazlett of the KMAG staff returned to the town near midnightand, upon learning of ADCOM's departure, drove on south to Choch'iwon wherethey stayed until morning, and then continued on to Taejon. The ROK Armyheadquarters remained in Suwon. After reaching Taejon on 1 July, ColonelWright sent five KMAG officers back to ROK Army headquarters. This headquartersremained in Suwon until 4 July. [27]

After securing Yongdungp'o on 3 July, the N.K. 4th Division preparedto continue the attack south. The next morning, at 0600, it departed onthe Suwon road with the 5th Regiment in the lead. Just before noonon 4 July, eleven enemy tanks with accompanying infantry were in Anyang-ni,halfway between Yongdungp'o and Suwon. The road from Suwon through Osantoward P'yongt'aek was almost solid with ROK Army vehicles and men movingsouth the afternoon and evening of 4 July. The 5th Regiment of the ROK2d Division attempted to delay the enemy column between Anyang-ni and Suwon,but fourteen T34 tanks penetrated its positions, completely disorganizedthe regiment, and inflicted on it heavy casualties. The Australian and U.S.Air Forces, striving to slow the North Korean advance, did not always hitenemy targets. On that day, 4 July, friendly planes strafed ROK troopsseveral times in the vicinity of Osan. The ROK Army headquarters left Suwonduring the day.

At midnight the N.K. 4th Division occupied the town. [28]

[1] Memo from Troop Control Br, May 51 OCMH Files.

[2] EUSAK WD, Prologue, 25 Jun-12 Jul 50, pp. ii, vi. The aggregate strength of the four divisions in Japan as of 30 June 1950 was as follows: 24th Infantry Division, 12,197; 25th Infantry Division,15,018; 1st Cavalry Division, 12,340; 7th Infantry Division, 12,907. Other troops in Japan included 5,290 of the 40th Antiaircraft Artillery, and 25,119 others, for a total of 82,871.

[3] Memo, Navy Dept for OCMH, Jun 51.

[4] Memo, Off Secy Air Force for OCMH, Jun 50. Other fighter squadrons were located as follows: 7 in the industrial area of central and northern Honshu, 4 on Okinawa, and 3 in the Philippines.

[5] U.S. Air Force Operations in the Korean Conflict 25 Jun-1 Nov 50, USAF Hist Study 71, 1 Jul 52, pp. 2-4.

[6] Ibid., p. 14.

[7] 24th Div WD, G-2 Jnl Msg File, 28 Jun 50.

[8] USAF Hist Study 71, p. 16; Hq X Corps, Staff Study, Development of Tactical Air Support in Korea, 25 Dec 50, p. 7.

[9] Memo, Navy Dept for OCMH, Jun 51.

[10] Msg, CINCFE to DA, dispatched Tokyo 030043, received Washington 021043 EDT.

[11] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in Korean War, ch. III, p. 11.

[12] Karig, et al., Battle Report: The War In Korea, pp. 58-59.

[13] USAF Hist Study 71, pp. 9-13; Hq X Corp., Staff Study, Development of Tactical Air Support in Korea, 25 Dec 50, pp. 7-8; Memo, Navy Dept for OCMH, Jun 51; Karig, et al., op. cit., pp. 75, 83

[14] Telecon 3441, FEC, Item 27, 1 Jul 50, Lt Gen M. B. Ridgway and Maj Gen C. A. Willoughby; Ltr, Lt Col Peter W. Scott to friend, ca. 6-7 Jul 50; Interv, author with Col Emmerich, 5 Dec 51; 24th Div WD, G-2 Jnl, 1 Jul 50.

[15] ATIS, Enemy Docs, Issue 4, Diary of N.K. soldier (unidentified), 16 Jun-31 Aug 50, entrys for 28-29 Jun, p. 10; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 100 (N.K. 6th Div), p. 33; Gen Paik Sun Yup, MS review comments, 11 Jul 58.

[16] There are extensive discussions of this subject in many prisoner interrogations in the ATIS documents.

[17] Church MS; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 96 (N.K. 3d Div), p. 30.

[18] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 94 (N.K. 4th Div), pp. 44-45; GHQ FEC, History of the N.K. Army, p. 58. The N.K, 6th Division claims to have entered Yongdungp'o 1 July, but this could have been only an approach to the city's edge. Ibid., Issue 100 (N.K. 6th Div), p. 33.

[19] Ibid., Issue 4 (Enemy Forces), p. 37; ADCOM G-3 Log, 3 Jul 50. Colonel Green, the ADCOM G-3 from GHQ, made this handwritten log available to the author in Tokyo in 1951. KMAG G-2 Unit History, 4 Jul 50.

[20] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in Korean War, ch. IV, p. 5.

[21] EUSAK WD, ,5 Jun-12 Jul 50, G-4 Unit Hist, 25-30 Jun 50, pp. 4-5.

[22] Church MS.

[23] Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer, 22 Feb 54; Ltr, Scott to friend, ca. 6-7 Jul 50; Church MS.

[24] Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer; Ltr, Scott to friend, ca. 6-7 Jul 50; Det X, 507th AAA AW Bn, Action Rpt, 30 Jun-3 Jul 50; 24th Div WD, G-2, Jnl, 25 Jun-3 July 50, verbal rpt by Lt Bailey of verbal orders he received to destroy AAA weapons and equipment at Suwon Airfield.

[25] Church MS; Interv, Capt Robert K. Sawyer with Lt Col Winfred A. Ross, 17 Dec 53. Ross was GHQ Signal member of ADCOM and was with General Church on the trip to Osan and during the night of 30 June.

[26] Church MS.

[27] Sawyer, KMAG MS; KMAG G-2 Jnl, 4 Jul 50; ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpt, Issue 94 (N.K. 4th Div), p. 45; Ltr, Scott to friend. Colonel Scott was one of the five officers who returned to Suwon on 1 July.

[28] ATIS Res Supp Interrog Rpts, Issue 94 (N.K. 4th Div), pp. 44-45; GHQ FEC, History of N.K. Army, p. 58; EUSAK WD, 20 Jul 50, G-2 Sec, ATIS Interrog Nr 89, 2d Lt Pak Mal Bang; ADCOM G-3 Log, 4 Jul 50.

|

|

- A VETERAN's Blog - |