|

|

CHAPTER IXEighth Army in Command |

The Foundation of Freedom is the Courage of Ordinary PeopleHistory |

| The conduct of war resembles the workings of an intricate machine withtremendous friction, so that combinations which are easily planned on papercan be executed only with great effort. |

| CARL VON CLAUSEWITZ, Principles of War |

By 6 July it was known that General MacArthur planned to have EighthArmy, with General Walker in command, assume operational control of thecampaign in Korea. General Walker, a native of Belton, Texas, already hadachieved a distinguished record in the United States Army. In World WarI he had commanded a machine gun company and won a battlefield promotion.Subsequently, in the early 1930's he commanded a battalion of the 15 InfantryRegiment in China. Before Korea he was best known, perhaps, for his commandof the XX Corps of General Patton's Third Army in World War II. GeneralWalker assumed command of Eighth Army in Japan in 148. Under General MacArthurhe commanded United Nations ground forces in Korea until his death in December150.

During the evening of 6 July General Walker telephoned Col. WilliamA. Collier at Kobe and asked him to report to him the next morning at Yokohama.When Collier arrived at Eighth Army headquarters the next morning GeneralWalker told him that Eighth Army was taking over command of the militaryoperations in Korea, and that he, Walker, was flying to Korea that afternoonbut was returning the following day. Walker told Collier he wanted himto go to Korea as soon as possible and set up an Eighth Army headquarters,that for the present Col. Eugene M. Landrum, his Chief of Staff, wouldremain in Japan, and that he, Collier, would be the Eighth Army combatChief of Staff in Korea until Landrum could come over later.

General Walker and Colonel Collier had long been friends and associatedin various commands going back to early days together at the Infantry Schoolat Fort Benning. They had seen service together in China in the 15th Infantryand in World War II when Collier was a member of Walker's IV Armored Corpsand XX Corps staffs. After that Collier had served Walker as Chief of Staffin command assignments in the United States. Colonel Collier had servedin Korea in 1948 and 1949 as Deputy Chief of Staff and then as Chief ofStaff of United States Army forces there. During that time he had come to know the country well.

On the morning of 8 July Colonel Collier flew from Ashiya Air Base toPusan and then by light plane to Taejon. After some difficulty he foundGeneral Dean with General Church between Taejon and the front. The daybefore, General Walker had told Dean that Collier would be arriving ina day or two to set up the army headquarters. General Dean urged Colliernot to establish the headquarters in Taejon, adding, "You can seefor yourself the condition." Collier agreed with Dean. He knew Taejonwas already crowded and that communication facilities there would be taxed.He also realized that the tactical situation denied the use of it for anarmy headquarters. Yet Colonel Collier knew that Walker wanted the headquartersas close to the front as possible. But if it could not be at Taejon, thenthere was a problem. Collier was acquainted with all the places south ofTaejon and he knew that short of Taegu they were too small and had inadequatecommunications, both radio and road, to other parts of South Korea, toserve as a headquarters. He also remembered that at Taegu there was a cablerelay station of the old Tokyo-Mukden cable in operation. So Collier droveto Taegu and checked the cable station. Across the street from it was alarge compound with school buildings. He decided to establish the EighthArmy headquarters there. Within two hours arrangements had been made withthe Provincial Governor and the school buildings were being evacuated.Collier telephoned Colonel Landrum in Yokohama to start the Eighth Armystaff to Korea. The next day, 9 July at 1300, General Walker's advanceparty opened its command post at Taegu. [1]

General Walker Assumes Command in Korea

As it chanced, the retreat of the U.S. 24th Infantry Division acrossthe Kum River on 12 July coincided with the assumption by Eighth UnitedStates Army in Korea (EUSAK) of command of ground operations. General Walkerupon verbal instructions from General MacArthur assumed command of allUnited States Army forces in Korea effective 0001 13 July. [2] That evening,General Church and his small ADCOM staff received orders to return to Tokyo,except for communications and intelligence personnel who were to remaintemporarily with EUSAK. A total American and ROK military force of approximately75,000 men, divided between 18,000 Americans and 58,000 ROK's, was thenin Korea. [3]

General Walker arrived in Korea on the afternoon of 13 July to assumepersonal control of Eighth Army operations. That same day the ROK Armyheadquarters moved from Taejon to Taegu to be near Eighth Army headquarters.General Walker at once established tactical objectives and unit responsibility.[4] Eighth Army was to delay the enemy advance, secure the current defensiveline, stabilize the military situation, and build up for future offensiveoperations. The 24th Division, deployed along the south bank of the KumRiver in the Kongju-Taejon area on the army's left (west) was to "preventenemy advance south of that line." To the east, in the mountainouscentral corridor, elements of the 25th Division were to take up blockingpositions astride the main routes south and help the ROK troops stop theNorth Koreans in that sector. Elements of the 25th Division not to exceedone reinforced infantry battalion were to secure the port of P'ohang-dongand Yonil Airfield on the east coast.

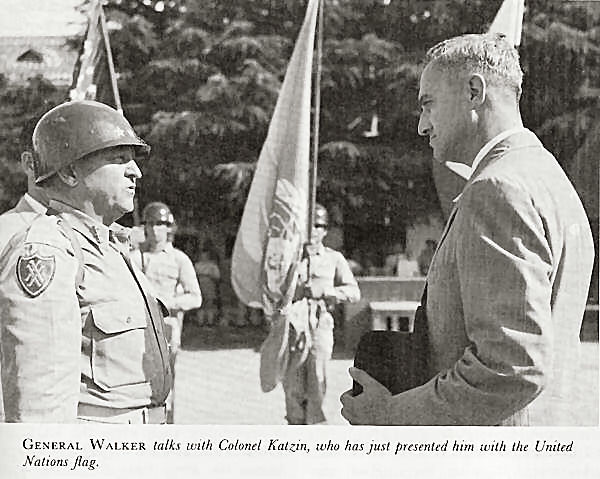

On 17 July, four days after he assumed command of Korean operations,General Walker received word from General MacArthur that he was to assumecommand of all Republic of Korea ground forces, pursuant to President SyngmanRhee's expressed desire. During the day, as a symbol of United Nationscommand, General Walker accepted from Col. Alfred G. Katzin, representingthe United Nations, the United Nations flag and hung it in his Eighth Armyheadquarters in Taegu. [5]

A word should be said about General MacArthur's and General Walker'scommand relationship over ROK forces. President Syngman Rhee's approvalof ROK forces coming under United Nations command was never formalizedin a document and was at times tenuous. This situation grew out of therelationship of the United Nations to the war in Korea.

On 7 July the Security Council of the United Nations took the thirdof its important actions with respect to the invasion of South Korea. Bya vote of seven to zero, with three abstentions and one absence, it passeda resolution recommending a unified command in Korea and asked the UnitedStates to name the commander. The resolution also requested the UnitedStates to provide the Security Council with "appropriate" reportson the action taken under a unified command and authorized the use of theUnited Nations flag. [6]

The next day, 8 July, President Truman issued a statement saying hehad designated General Douglas MacArthur as the "Commanding Generalof the Military Forces," under the unified command. He said he alsohad directed General MacArthur "to use the United Nations flag inthe course of operations against the North Korean forces concurrently withthe flags of the various nations participating." [7]

The last important act in establishing unified command in Korea tookplace on 14 July when President Syngman Rhee of the Republic of Korea placedthe security forces of the Republic under General MacArthur, the UnitedNations commander. [8]

Although there appears to be no written authority from President Rheeon the subject, he verbally directed General Chung Il Kwon, the ROK ArmyChief of Staff, to place himself under the U.N. Command. Under his authoritystemming from General MacArthur, the U.N. commander, General Walker directedthe ROK Army through its own Chief of Staff. The usual procedure was forGeneral Walker or his Chief of Staff to request the ROK Army Chief of Staffto take certain actions regarding ROK forces. That officer or his authorizeddeputies then issued the necessary orders to the ROK units. This arrangementwas changed only when a ROK unit was attached to a United States organization.The first such major action took place in September 1950 when the ROK 1stDivision was attached to the U.S. I Corps. About the same time the ROK17th Regiment was attached to the U.S. X Corps for the Inch'on landing.Over such attached units the ROK Army Chief of Staff made no attempt toexercise control. Actually the ROK Army authorities were anxious to dowith the units remaining nominally under their control whatever the commandinggeneral of Eighth Army wanted. From a military point of view there wasno conflict on this score. [9]

When political issues were at stake during certain critical phases ofthe war it may be questioned whether this command relationship would havecontinued had certain actions been taken by the U.N. command which PresidentSyngman Rhee considered inimical to the political future of his country.One such instance occurred in early October when U.N. forces approachedthe 38th Parallel and it was uncertain whether they would continue militaryaction into North Korea. There is good reason to believe that Syngman Rheegave secret orders that the ROK Army would continue northward even if orderedto halt by the U.N. command, or that he was prepared to do so if it becamenecessary. The issue was not brought to a test in this instance as theU.N. command did carry the operations into North Korea.

Troop Training and Logistics

General Walker had instituted a training program beginning in the summerof 1949 which continued on through the spring of 1950 to the beginningof the Korean War. It was designed to give Eighth Army troops some degreeof combat readiness after their long period of occupation duties in Japan.When the Korean War started most units had progressed through battaliontraining, although some battalions had failed their tests. [10] Regimental,division, and army levels of training and maneuvers had not been carriedout. The lack of suitable training areas in crowded Japan constituted oneof the difficulties.

If the state of training and combat readiness of the Eighth Army unitsleft much to be desired on as June 1950, so also did the condition of theirequipment. Old and worn would describe the condition of the equipment ofthe occupation divisions in Japan. All of it dated from World War II. Somevehicles would not start and had to be towed on to LST's when units loadedout for Korea. Radiators were clogged, and over-heating of motors was frequent.The poor condition of Korean roads soon destroyed already well-worn tiresand tubes. [11]

The condition of weapons was equally bad. A few examples will reflectthe general condition. The 3d Battalion of the 35th Infantry Regiment reportedthat only the SCR-300 radio in the battalion command net was operable whenthe battalion was committed in Korea. The 24th Regiment at the same timereported that it had only 60 percent of its Table of Equipment allowanceof radios and that four-fifths of them were inoperable. The 1st Battalionof the 35th Infantry had only one recoilless rifle; none of its companieshad spare barrels for machine guns, and most of the M1 rifles and M2 carbineswere reported as not combat serviceable. Many of its 60-mm. mortars wereunserviceable because the bipods and the tubes were worn out. Cleaningrods and cleaning and preserving supplies often were not available to thefirst troops in Korea. And there were shortages in certain types of ammunitionthat became critical in July. Trip flares, 60-mm. mortar illuminating shells,and grenades were very scarce. Even the 60-mm. illuminating shells thatwere available were old and on use proved to be 50 to 60 percent duds. [12]

General Walker was too good a soldier not to know the deficiencies ofhis troops and their equipment. He went to Korea well aware of the limitationsof his troops in training, equipment, and in numerical strength. He didnot complain about the handicaps under which he labored. He tried to carryout his orders. He expected others to do the same.

On 1 July the Far East Command directed Eighth Army to assume responsibilityfor all logistical support of the United States and Allied forces in Korea.[13] This included the ROK Army. When Eighth Army became operational inKorea, this logistical function was assumed by Eighth Army Rear which remainedbehind in Yokohama. This dual function of Eighth Army-that of combat inKorea and of logistical support for all troops fighting in Korea-led tothe designation of that part of the army in Korea as Eighth United StatesArmy in Korea. This situation existed until 25 August. On that date theFar East Command activated the Japan Logistical Command with Maj. Gen.Walter L. Weible in command. It assumed the logistical duties previouslyheld by Eighth Army Rear.

The support of American troops in Korea, and indeed of the ROK Armyas well, would have to come from the United States or Japan. Whatever couldbe obtained from stocks in Japan or procured from Japanese manufacturerswas so obtained. Japanese manufacturers in July began making antitank minesand on 18 July a shipment of 3,000 of them arrived by boat at Pusan.

That equipment and ordnance supplies were available to the United Statesforces in Korea in the first months of the war was largely due to the "roll-up"plan of the Far East Command. It called for the reclamation of ordnanceitems from World War II in the Pacific island outposts and their repairor reconstruction in Japan. This plan had been conceived and started in1948 by Brig. Gen. Urban Niblo, Ordnance Officer of the Far East Command.[14] During July and August 1950 an average of 4,000 automotive vehiclesa month cleared through the ordnance repair shops; in the year after theoutbreak of the Korean War more than 46,000 automotive vehicles were repairedor rebuilt in Japan.

The Tokyo Ordnance Depot, in addition to repairing and renovating WorldWar II equipment for use in Korea, instituted a program of modifying certainweapons and vehicles to make them more effective in combat. For instance,M4A3 tanks were modified for the replacement of the 75-mm. gun with thehigh velocity 76-mm. gun, and the motor carriage of the 105-mm. gun wasmodified so that it could reach a maximum elevation of 67 degrees to permithigh-angle fire over the steep Korean mountains. Another change was inthe half-track M15A1, which was converted to a T19 mounting a 40-mm. guninstead of the old model 37-mm. weapon. [15]

Of necessity, an airlift of critically needed items began almost atonce from the United States to the Far East. The Military Air TransportService (MATS), Pacific Division, expanded immediately upon the outbreakof the war. The Pacific airlift was further expanded by charter of civilairlines planes. The Canadian Government lent the United Nations a RoyalCanadian Air Force squadron of 6 transports, while the Belgian Governmentadded several DC-4's. [16] Altogether, the fleet of about 60 four-enginetransport planes operating across the Pacific before 25 June 1950 was quicklyexpanded to approximately 250. In addition to these, there were MATS C-74and C-97 planes operating between the United States and Hawaii.

The Pacific airlift to Korea operated from the United States over threeroutes. These were the Great Circle, with flight from McChord Air ForceBase, Tacoma, Washington, via Anchorage, Alaska and Shemya in the Aleutiansto Tokyo, distance 5,688 miles and flying time 30 to 33 hours; a secondroute was the Mid-Pacific from Travis (Fairfield-Suisun) Air Force Basenear San Francisco, Calif., via Honolulu and Wake Island to Tokyo, distance6,718 miles and flying time 34 hours; a third route was the Southern, fromCalifornia via Honolulu, and Johnston, Kwajalein, and Guam Islands to Tokyo,distance about 8,000 miles and flying time 40 hours. The airlift movedabout 106 tons a day in July 1950. [17]

From Japan most of the air shipments to Korea were staged at Ashiyaor at the nearby secondary airfields of Itazuke and Brady.

Subsistence for the troops in Korea was not the least of the problemsto be solved in the early days of the war. There were no C rations in Koreaand only a small reserve in Japan. The Quartermaster General of the UnitedStates Army began the movement at once from the United States to the FarEast of all C and 5-in-1 B rations. Field rations at first were largelyWorld War II K rations.

Subsistence of the ROK troops was an equally important and vexing problem.The regular issue ration to ROK troops was rice or barley and fish. Itconsisted of about twenty-nine ounces of rice or barley, one half poundof biscuit, and one half pound of canned fish with certain spices. Oftenthe cooked rice, made into balls and wrapped in cabbage leaves, was sourwhen it reached the combat troops on the line, and frequently it did notarrive at all. Occasionally, local purchase of foods on a basis of 200won a day per man supplemented the issue ration (200 won ROK money equaled5 cents U.S. in value). [18]

An improved ROK ration consisting of three menus, one for each dailymeal, was ready in September 1950. It provided 3,210 calories, weighed2.3 pounds, and consisted of rice starch, biscuits, rice cake, peas, kelp,fish, chewing gum, and condiments, and was packed in a waterproofed bag.With slight changes, this ration was found acceptable to the ROK troopsand quickly put into production. It became the standard ration for them during the first year of the war. [19]

On 30 June, Lt. Col. Lewis A. Hunt led the vanguard of American officersarriving in Korea to organize the logistical effort there in support ofUnited States troops. Less than a week later, on 4 July, Brig. Gen. CrumpGarvin and members of his staff arrived at Pusan to organize the PusanBase Command, activated that day by orders of the Far East Command. Thiscommand was reorganized on 13 July by Eighth Army as the Pusan LogisticalCommand, and further reorganized a week later. The Pusan Logistical Commandserved as the principal logistical support organization in Korea until19 September 1950 when it was redesignated the 2d Logistical Command. [20]

The Port of Pusan and Its Communications

It was a matter of the greatest good fortune to the U.N. cause thatthe best port in Korea, Pusan, lay at the southeastern tip of the peninsula.Pusan alone of all ports in South Korea had dock facilities sufficientlyample to handle a sizable amount of cargo. Its four piers and interveningquays could berth twenty-four or more deepwater ships, and its beachesprovided space for the unloading of fourteen LST's, giving the port a potentialcapacity of 45,000 measurement tons daily. Seldom, however, did the dailydischarge of cargo exceed 14,000 tons because of limitations such as theunavailability of skilled labor, large cranes, cars, and trucks. [21]

The distance in nautical miles to the all-important port of Pusan fromthe principal Japanese ports varied greatly. From Fukuoka it was 110 miles;from Moji, 123; from Sasebo, 130; from Kobe, 361; and from Yokohama (viathe Bungo-Suido strait, 665 miles), 900 miles. The sea trip from the westcoast of the United States to Pusan for personnel movement required about16 days; that for heavy equipment and supplies on slower shipping schedulestook longer.

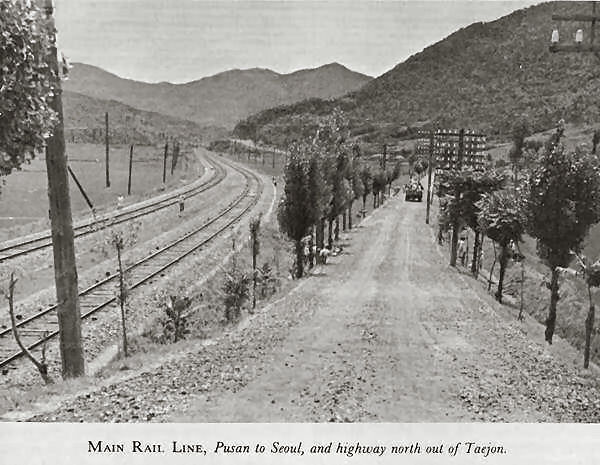

From Pusan a good road system built by the Japanese and well ballastedwith crushed rock and river gravel extended northward. Subordinate lines ran westward along the south coast through Masan and Chinju and northeastnear the east coast to P'ohang-dong. There the eastern line turned inlandthrough the east-central mountain area. The roads were the backboneof the U.N. transportation system in Korea.

The approximately 20,000 miles of Korean vehicular roads were all ofa secondary nature as measured by American or European standards. Eventhe best of them were narrow, poorly drained, and surfaced only with gravelor rocks broken laboriously by hand, and worked into the dirt roadbed bythe traffic passing over it. The highest classification placed on any appreciablelength of road in Korea by Eighth Army engineers was for a gravel or crushedrock road with gentle grades and curves and one and a half to two lanes wide. According to engineer specifications there wereno two-lane roads, 22 feet wide, in Korea. The average width of the bestroads was 18 feet with numerous bottlenecks at narrow bridges and bypasseswhere the width narrowed to 11-13 feet. Often on these best roads therewere short stretches having sharp curves and grades up to 15 percent. TheKorean road traffic was predominately by oxcart. The road net, like the net, was principally north-south, with a few lateral east-west connectingroads. [22]

American Command Estimate

Almost from the outset of American intervention, General MacArthur hadformulated in his mind the strategical principles on which he would seekvictory. Once he had stopped the North Koreans, MacArthur proposed to usenaval and air superiority to support an amphibious operation in their rear.By the end of the first week of July he realized that the North KoreanArmy was a formidable force. His first task was to estimate with reasonableaccuracy the forces he would need to place in Korea to stop the enemy andfix it in place, and then the strength of the force he would need in reserve to land behind the enemy's line. That the answerto these problems was not easy and clearly discernible at first will becomeevident when one sees how the unfolding tactical situation in the firsttwo months of the war compelled repeated changes in these estimates.

By the time American ground troops first engaged North Koreans in combatnorth of Osan, General MacArthur had sent to the Joint Chiefs of Staffin Washington by a liaison officer his requests for heavy reinforcements,most of them already covered by radio messages and teletype conferences.His requests included the 2d Infantry Division, a regimental combat teamfrom the 82d Airborne Division, a regimental combat team and headquartersfrom the Fleet Marine Force, the 2d Engineer Special Brigade, a Marinebeach group, a Marine antiaircraft battalion, 700 aircraft, 2 air squadronsof the Fleet Marine Force, a Marine air group echelon, 18 tanks and crewpersonnel, trained personnel to operate LST's, LSM's, and LCVP's, and 3medium tank battalions, plus authorization to expand existing heavy tankunits in the Far East Command to battalion strength. [23]

On 6 July, the Joint Chiefs of Staff requested General MacArthur tofurnish them his estimate of the total requirements he would need to clearSouth Korea of North Korean troops. He replied on 7 July that to halt andhurl back the North Koreans would require, in his opinion, from four tofour and a half full-strength infantry divisions, an airborne regimentalcombat team complete with lift, and an armored group of three medium tankbattalions, together with reinforcing artillery and service elements. Hesaid 30,000 reinforcements would enable him to put such a force in Koreawithout jeopardizing the safety of Japan. The first and overriding essential,he said, was to halt the enemy advance. He evaluated the North Korean effortas follows: "He is utilizing all major avenues of approach and hasshown himself both skillful and resourceful in forcing or enveloping suchroad blocks as he has encountered. Once he is fixed, it will be my purposefully to exploit our air and sea control, and, by amphibious maneuver,strike him behind his mass of ground force." [24]

By this time General MacArthur had received word from Washington thatbomber planes, including two groups of B-29's and twenty-two B-26's, wereexpected to be ready to fly to the Far East before the middle of the month.The carrier Boxer would load to capacity with F-51 planes and sailunder forced draft for the Far East. But on 7 July Far East hopes for aspeedy build-up of fighter plane strength to tactical support of the groundcombat were dampened by a message from Maj. Gen. Frank F. Everest, U.S.Air Force Director of Operations. He informed General Stratemeyer thatforty-four of the 164 F-80's requested were on their way, but that the rest could not be sent because the Air Force did not have them. [25]

To accomplish part of the build-up he needed to carry out his plan ofcampaign in Korea, MacArthur on 8 July requested of the Department of theArmy authority to expand the infantry divisions then in the Far East Commandto full war strength in personnel and equipment. He received this authorityon 19 July. [26]

Meanwhile, from Korea General Dean on 8 July had sent to General MacArthuran urgent request for speedy delivery of 105-mm. howitzer high-explosiveantitank shells for direct fire against tanks. Dean said that those ofhis troops who had used the 2.36-inch rocket launcher against enemy tankshad lost confidence in the weapon, and urged immediate air shipment fromthe United States of the 3.5-inch rocket launcher. He gave his opinionof the enemy in these words, "I am convinced that the North KoreanArmy, the North Korean soldier, and his status of training and qualityof equipment have been under-estimated." [27]

The next day, 9 July, General MacArthur considered the situation sufficientlycritical in Korea to justify using part of his B-29 medium bomber forceon battle area targets. He also sent another message to the Joint Chiefsof Staff, saying in part:

The situation in Korea is critical...

His [N.K.] armored equip[ment] is of the best and the service thereof,as reported by qualified veteran observers, as good as any seen at anytime in the last war. They further state that the enemy's inf[antry] isof thoroughly first class quality.

This force more and more assumes the aspect of a combination of Sovietleadership and technical guidance with Chinese Communist ground elements.While it serves under the flag of North Korea, it can no longer be consideredas an indigenous N.K. mil[itary] effort.

I strongly urge that in add[ition] to those forces already requisitionedan army of at least four divisions, with all its component services, bedispatched to this area without delay and by every means of transportationavailable.

The situation has developed into a major operation. [28]

Upon receiving word the next day that the 2d Infantry Division and certainarmor and antiaircraft artillery units were under orders to proceed tothe Far East, General MacArthur replied that same day, 10 July, requestingthat the 2d Division be brought to full war strength, if possible, withoutdelaying its departure. He also reiterated his need of the units requiredto bring the 4 infantry divisions already in the Far East to full war strength.He detailed these as 4 heavy tank battalions, 12 heavy tank companies,11 infantry battalions, 11 field artillery battalions (105-mm. howitzers),and 4 antiaircraft automatic weapons battalions (AAA AW), less four batteries.[29]

After the defeat of the 24th Division on 11 and 12 July north of Choch'iwon, General Walker decided to request immediate shipment to Korea of theground troops nearest Korea other than those in Japan. These were the twobattalions on Okinawa. Walker's chief of staff, Colonel Landrum, calledGeneral Almond in Tokyo on 12 July and relayed the request. The next day,General MacArthur ordered the Commanding General, Ryukyus Command, to preparethe two battalions for water shipment to Japan. [30] The worsening tacticalsituation in Korea caused General MacArthur on 13 July to order GeneralStratemeyer to direct the Far East Air Forces to employ maximum B-26 andB-29 bomber effort against the enemy divisions driving down the centerof the Korean peninsula. Two days later he advised General Walker thathe would direct emergency use of the medium bombers against battle-fronttargets whenever Eighth Army requested it. [31]

It is clear that by the time the 24th Division retreated across theKum River and prepared to make a stand in front of Taejon there was nocomplacency over the military situation in Korea in either Eighth Armyor the Far East Command. Both were thoroughly alarmed.

[1] Brig Gen William A. Collier, MS review comments, 10 Mar 58: EUSAK WD. 25 Jun-12 Jul 50, Prologue, p. xiv.

[2] EUSAK GO 1, 13 Jul 50; EUSAK WD, G-3, Sec, 13 Jul 50; Church MS.

[3] ADCOM reached Tokyo the afternoon of 15 July. See EUSAK WD, 13 Jul 50, for American organizations' strength ashore. ROK strength is approximate.

[4] EUSAK WD, G-3 Sec, 13 Jul 50, Opn Ord 100.

[5] EUSAK GO 3, 17 Jul 50; EUSAK WD and G-3 Sec, 17 Jul 50.

[6] Dept of State Pub 4263, United States Policy in the Korean Conflict, July 1950-February 1951, p. 8. Abstentions in the vote: Egypt, India, Yugoslavia. Absent: Soviet Union. For text of the Security Council resolution of 7 July see Document 99, pages 60-67.

[7] Ibid., Doc. 100, p. 67, gives text of the President's statement. The JCS sent a message to General MacArthur on 10 July informing him of his new United Nations command.

[8] Ibid., p. 47.

[9] Ltr. Lt Gen Francis W. Farrell to author, 11 Jun 58. General Farrell was Chief of KMAG and served as ranking liaison man for Generals Walker, Ridgway, and Van Fleet with the ROK Army for most of the first year of the war. He confirms the author's understanding of this matter.

[10] Schnabel, Theater Command, treats this subject in some detail.

[11] 24th Div WD, G-4 Daily Summ, 7-8 Jul 50.

[12] 24th Inf WD, 6-31 Jul 50; 1st Bn, 35th Inf (25th Div) Unit Rpt, 12-31 Jul, and 1-6 Aug 50; 24th Div WD, G-4 Sec, Daily Summ, 3-4 Aug 50, p. 113, and Hist Rpt, 23 Jul-25 Aug 50.

[13] GHQ FEC, Ann Narr Hist Rpt, 1 Jan-31 Oct 50, p. 43.

[14] GHQ FEC, Ann Narr Hist Rpt, 1 Jan-31 Oct 50, p. 50; Brig. Gen. Gerson K. Heiss, "Operation Rollup," Ordnance (September-October, 1951), 242-45.

[15] Heiss, "Operation Rollup," op. cit., pp. 242-45.

[16] Maj. Gen. Lawrence S. Kuter, "The Pacific Airlift," Aviation Age, XV, No. 3 (March, 1951) 16-17.

[17] Maj. James A. Huston. Time and Space, pt. VI, pp. 93-94, MS in OCMH.

[18] Interv, author with Capt Darrigo, 5 Aug 53. (Darrigo lived with ROK troops for several months in 1950.)

[19] Capt. Billy C. Mossman and 1st Lt. Harry J. Middleton, Logistical Problems and Their Solutions, pp. 50-51, MS in OCMH.

[20] Pusan Logistical Command Monthly Activities Rpt, Jul 50, Introd and p. 1; Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in Korean War, ch. III, pp. 3, 6, and ch. 4, pp. 8-9.

[21] Pusan Log Comd Rpt, Jul 50.

[22] EUSAK WD, 10 Sep 50, Annex to G-3 Hist Rpt.

[23] FEC, C-3 Opns, Memo for Record, 5 Jul 50, sub: CINCFE Immediate Requirements, cited in Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. 111, p. 17.

[24] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. III, p. 16, citing Msg JCS 85058 to CINCFE, 6 Jul and Msg C 57379, CINCFE to DA, 7 Jul 50.

[25] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in Korean War, ch. V, pp. 18-39, citing Msg JCS 84876, JCS to CINCFE, 3 Jul 50; USAF Hist Study 71, p. 16.

[26] GHQ FEC, Ann Narr Hist Rpt, 1 Jan-31 Oct 50, p. 11.

[27] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. III, p. 8, citing Ltr, Dean to CINCFE, 080800 Jul 50, sub: Recommendations Relative to the Employment of U.S. Army Troops in Korea.

[28] Msg, CINCFE to JCS, 9 Jul 50; Hq X Corps, Staff Study, Development of Tactical Air Support in Korea, 25 Dec 50, p. 8.

[29] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in Korean War, ch. III, pp. 19-20, citing Msg CX57573, CINCFE to DA, 10 Jul 50.

[30] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War. ch. III, p. 21; Digest of fonecon, Landrum and Almond, FEC G-3, 12 Jul 50.

[31] USAF Hist Study 71, pp. 22-23.

|

|

- A VETERAN's Blog - |